Christmas 1969 brought me the first childhood vehicle I clearly recall: a Murray Tot Rod pedal car. I had a tricycle before it, and two different bicycles after it to round out my childhood vehicles before I got my first automobile in 1981. Looking back, my favorite vehicle to drive was the Toyota Celica Supra I drove in my twenties, but the Murray Tot Rod isn’t far behind.

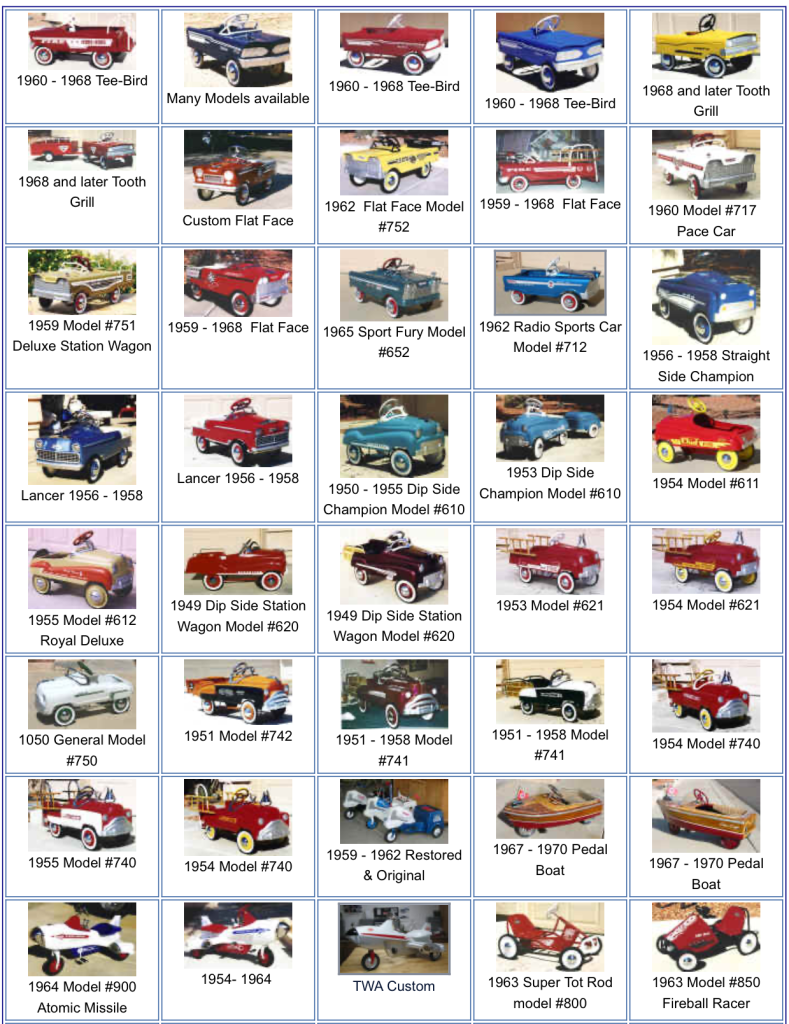

Murray Ohio Manufacturing Company was founded in 1919 to make auto parts like fenders and fuel tanks. They began making bicycles in the Great Depression, selling them through retailers like Sears, Roebuck & Co. After World War II, they concentrated on low-cost bicycles and making pedal cars. Below are just some of their pedal car models.

The Super Tot Rod 800 in the bottom row was similar to my green machine.

Here I am enjoying my new Tot Rod:

We moved to Bethany after I graduated from kindergarten, and I continued to use the Tot Rod for a few more years. Our house in Bethany was on three lots, with lots of room on both side lots. We lived in the Cross Timbers, with sandy soil and about 70 trees, mostly Blackjack oaks.

My best friend in elementary school was the late Gene Freeman. Gene loved vehicles even more than I did, and he had a Big Wheel.

Gene and I would rake the countless oak leaves into huge piles, forming winding pathways for us to race along, me in my pedal car and Gene in his Big Wheel, which was a huge hit toy in 1971 and 1972. I remember us raking a couple of “parking spots” for our vehicles outside one of the walls of my bedroom.

I’d seen television ads that made the Big Wheel look like a lot of fun:

But I found it much harder to pedal and control than my Murray Hot Rod, and Gene had already pulled so hard on the brake handle that it had busted. So I was happy to stick with my Murray Tot Rod.

Eventually I could no longer squeeze into my Tot Rod. I wound up taking over a purple Schwinn Sting-Ray bike my mother had bought and placed in a mount to use as an exercise machine.

Ignaz Schwinn was a German immigrant backed by fellow German American Adolph Frederick William Arnold, a meat packer, who founded Arnold, Schwinn & Company in 1895. By 1950, most U.S. bicycle manufacturers sold in bulk to department stores, who rebranded the bikes. Schwinn stopped producing such private label bikes in 1950, except for B.F. Goodrich branded bikes sold in tire stores.

Schwinn had a dominant position in the U.S. market by the late 1950s and advertised heavily on television in the 1960s, sponsoring Captain Kangaroo. In 1962, Schwinn’s designer Al Fritz heard about a youth trend in California of retrofitting bikes with “chopper” style motorcycle accountrements, such as high-rise “ape-hanger” handlebars and low-ride “banana seats”. His wheelie bike, the Sting-Ray, was introduced in 1963.

Despite loving Captain Kangaroo when I was little, I wasn’t excited to be getting my mother’s purple Sting-Ray. It struck me as silly and showy. I insisted that a frilly white plastic woven basket be removed from its front, and I cut off the streamers that extended from the end of each handlebar.

My father tried putting training wheels on it for me, but I didn’t like them, and he wound up taking them off. I just lurched around a side yard to learn to ride, where there always seemed to be a Blackjack oak ready to catch me when I lost my balance. The rough bark on those trees was a great incentive for improvement.

I did enjoy that I could actually ride the bike on the street, and I added a metal basket to the front so I could carry groceries home from the old neighborhood market some blocks away.

I was unhappy about the color of my bike, so I made a sign reading Purple People Eater which I affixed over the chain guard, turning it into a joke. Eventually I added a speedometer, but the bike had only one gear and a coaster brake, so I didn’t break any speed records on it.

In junior high, my father bought a couple of AMF Scorcher ten-speed bicycles at a garage sale, and I made good use of one around Windsor Hills, visiting friends and riding down to the big shopping center.

American Machine and Foundry began in 1900 in New York. It evolved into part of what Eisenhower termed “the military-industrial complex” after World War II. In 1950, it purchased the Roadmaster line of bicycles from the Cleveland Welding Company. Its operations shifted from Cleveland, Ohio to Little Rock, Arkansas before moving to a new factory in Olney, Illinois. That is where our bicycles would have been manufactured, and they weren’t considered quality bikes.

My ten-speed’s cheap brakes and gear mechanisms required adjustment, and Dad wasn’t familiar with any of that. So I bought Richard’s Bicycle Book to help me learn how to keep my bike working. Richard Ballantine was the son of Ian and Betty Ballantine of Ballantine Books, which I was familiar with as a major publisher of science fiction. Richard was a cycling writer, journalist, and advocate. He freely expressed his views in his book, which was first published in 1972 and had several later editions.

When my friends and I would go off-road on our bikes, cockleburs would puncture the tires and inner tubes. I couldn’t afford to replace the inner tubes regularly, so I would remove the wheel, use a screwdriver to remove the tire and inner tube, and vulcanize patches onto the tubes using a kit I purchased at the local T.G.&Y. discount store.

I eventually outfitted my ten speed with a speedometer and a headlight. Since I was bicycling to and from a friend’s house after dark, I had a Rampar battery-powered light that I strapped to my lower leg. That light bobbing up and down helped make me more visible to drivers.

I was grateful to have it for transportation, but the ten-speed was just a tool. Once I could drive, I seldom rode it much. I brought it to Bartlesville, but it was difficult to transport to one of the entrances to the Pathfinder Parkway, the paved 12-mile trail system linking the city’s major parks, and I had zero interest in riding a bike on city streets.

I later bought a 21-speed bike with a quick-release front wheel. I used to ride it on the Pathfinder Parkway, using a bell to warn pedestrians that I would pass. By then I had wised up and wore a bike helmet, although I never liked doing so. For many years I’ve left the bike and helmet at home and simply walked along the Parkway. I don’t mind the slower pace now that I can easily listen to an audiobook or music with my iPhone and some earbuds.

I see kids on bicycles on the Parkway, but mostly younger ones with parents. Occasionally I’ll see teenagers, who are usually in a hurry. I’ve never seen a Tot Rod on the Parkway, and while that doesn’t surprise me, it certainly would be a treat to see one pedaled by.