April 25, 2021

April 25, 2021

Soon the Pandemic Response Committee I chair in our school district will conduct its 50th meeting since March 6, 2020. I provide this overview of our experience as we enter a welcome new phase of the pandemic: it has been five weeks since we had a new positive staff case, we’ve had no new student cases for two weeks, and we only have three out of over 5,800 students in close contact quarantine, all due to non-school exposures.

Those remarkably low numbers may not hold, but I don’t expect them to explode, either. So I’m consulting my COVID-19 crystal ball as I contemplate how to adapt. Even though hygiene theater has finally been discounted, I still can’t rub my hands across my crystal ball’s glassy surface, since it is studded with spike proteins. But I can gaze into it to dimly perceive what life in our schools might well be like for the rest of 2021.

The Trail We Have Trod

To plot our path from here, we need to look back at the tortuous trail we have trod. In the summer of 2020, our committee painstakingly devised detailed procedures to resume in-person instruction in August 2020. The initial drafts were repeatedly amended after feedback from regular physically distanced meetings in a Johnstone Park outdoor pavilion with our district administrators, after parent and staff surveys, and after distanced public meetings at our high school stadium as well as staff and school board webinars.

We had to review rapidly evolving and often conflicting guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Oklahoma State Department of Health (OSDH), and Oklahoma State Department of Education (OSDE). A few were adopted, many were adapted, and some were discarded.

Offering both in-person and virtual instruction for all

An instructional decision that came early on from Supt. McCauley was to offer both in-person instruction and full-time virtual classes every day to all students. We had seen the learning losses when the state suspended in-person classes from Spring Break to the end of the 2019-2020 school year in late May and realized that, while we had 1:1 Chromebooks in our middle and high schools, we couldn’t acquire enough Chromebooks to outfit each elementary student until early fall. So unlike some urban school districts, we decided that offering daily in-person instruction to all, except for planned and ad hoc distance learning days, was important to fulfilling our district mission.

Distancing strategies I developed

We started the school year in August 2020 with almost one in five students fully virtual. With over 80% of our students still in-person, offering daily in-person classes meant we had to ignore the six-foot spacing distancing the CDC recommended. Research said three to four feet should still help a lot, so I advised staff to aim for that as a desirable minimum. We successfully followed that course for seven months before the CDC finally said three feet would do.

Face coverings has been another major issue for us. All along we deliberately omitted students below the 4th Grade from the requirements, based on early research that the youngest students should have a lower rate of infection with fewer symptoms. But for everyone else we ratcheted up our requirements in the fall and winter from face coverings when in close contact to at all times, and eventually banned face shields for over three months in early 2021. During the winter surge I strongly recommended N95 masks for high-risk staff members. So our face covering guidance has always strayed from CDC guidelines in various ways. Blair Ellis, the Executive Director of the Bartlesville Public Schools Foundation, and Dr. Stephanie Curtis, BPSD’s Executive Director of Personnel & School Support, were instrumental in acquiring various forms of personal protective equipment for students and staff which Kerry Ickleberry, our Director of Health & Safety, helped distribute.

Face coverings has been another major issue for us. All along we deliberately omitted students below the 4th Grade from the requirements, based on early research that the youngest students should have a lower rate of infection with fewer symptoms. But for everyone else we ratcheted up our requirements in the fall and winter from face coverings when in close contact to at all times, and eventually banned face shields for over three months in early 2021. During the winter surge I strongly recommended N95 masks for high-risk staff members. So our face covering guidance has always strayed from CDC guidelines in various ways. Blair Ellis, the Executive Director of the Bartlesville Public Schools Foundation, and Dr. Stephanie Curtis, BPSD’s Executive Director of Personnel & School Support, were instrumental in acquiring various forms of personal protective equipment for students and staff which Kerry Ickleberry, our Director of Health & Safety, helped distribute.

Contact tracing

Given those deviations from the CDC recommendations, it was important for us to identify and contain any potential superspreaders from our in-person offerings. In June, I completed a 7-hour contact tracer training course from Johns Hopkins. Eventually over 40 district staff members would complete that training, with dozens of them spending untold hours isolating positive cases, identifying and quarantining close contacts, and following up with families. I developed our internal tracking system, which includes a live public view of our student and staff isolations and quarantines by site, and shared historical timeline charts. Our hardworking contact tracers, led by Health & Safety Director Kerry Ickleberry, maintained our robust and fully-CDC-compliant student contact tracing effort throughout the school year. District Nurse Lisa Foreman has brought an invaluable health perspective to our committee decision-making and the ongoing contact tracing. Meanwhile, the state’s own contact tracing program utterly collapsed and was eventually judged to have “had no measurable impact on the pandemic” with a lack of timely and accessible data.

Given those deviations from the CDC recommendations, it was important for us to identify and contain any potential superspreaders from our in-person offerings. In June, I completed a 7-hour contact tracer training course from Johns Hopkins. Eventually over 40 district staff members would complete that training, with dozens of them spending untold hours isolating positive cases, identifying and quarantining close contacts, and following up with families. I developed our internal tracking system, which includes a live public view of our student and staff isolations and quarantines by site, and shared historical timeline charts. Our hardworking contact tracers, led by Health & Safety Director Kerry Ickleberry, maintained our robust and fully-CDC-compliant student contact tracing effort throughout the school year. District Nurse Lisa Foreman has brought an invaluable health perspective to our committee decision-making and the ongoing contact tracing. Meanwhile, the state’s own contact tracing program utterly collapsed and was eventually judged to have “had no measurable impact on the pandemic” with a lack of timely and accessible data.

With four weeks of classes left in this school year, we have isolated 321 student cases and imposed 4,794 student quarantines. And in all of that, it is very important for our future planning to note that we have seen no clear signals of school-based spread. We didn’t have any signals of in-school spread even during a stressful peak of student and staff cases in late January and early February, which was happily brought under control by a two-week lockdown from Mother Nature when ice, snow, and severe cold shut down classes and much of the other activity in Bartlesville.

The 1 week of DL then Winter Break in that chart is when we cancelled in-person classes for the final week of the first semester as our local hospital ICU was overwhelmed with COVID-19 cases. That and Winter Break kept everyone out of the schools for three weeks during the worst of the winter surge for hospitals in the state’s NE Region 2, although the overall impact on Tulsa hospitals peaked a few weeks later in mid-January.

Distance learning days

Shifting to sitewide or districtwide distance learning was another example of us charting our own course. The OSDE alert level guidelines we initially adopted in August were soon abandoned when it became apparent there was poor coupling of student and staff case rates with that of the county as a whole. We endured the criticism that we were shifting the goal posts, recognizing that our protocols needed to evolve with experience. We should end this school year with 151 days of in-person instruction, whereas if we had stuck with the OSDE guidelines, we would have had less than 60 days. Our committee decoupled all of our protocols from them until recent weeks, instead relying on citywide, student, and staff case rates as well as hospital metrics to guide when to tighten or relax our protocols and trigger any sitewide or districtwide distance learning periods.

This academic year we had 16 districtwide distance learning days, 9 inclement weather days, and put Central Middle School into distance learning for two additional days due to high student/staff case rates. Bartlesville High School had one distance learning day early on to allow for deep cleaning, and that experience led us to refine our deep cleaning protocols to avoid additional closures.

That deviation also eventually turned out to be the right call, with the CDC finally acknowledging, over a year after the pandemic became a nationwide phenomenon, that disinfecting surfaces does little to reduce the transmission of COVID-19. We now know that the risk of contracting the virus from touching a contaminated surface is less than 0.01%. The run on hand sanitizer last year turned out to be pointless, since COVID-19 is transmitted by breathing, not touching. Having the CDC finally admit that, many months after a scientific consensus had formed, has finally allowed us to discontinue unnecessary deep cleaning with no pushback. Yet even now the CDC still advises everyone to perform hygiene theater when a positive case was around within the past 24 hours, which strikes me as more about appearances than reality.

Pick a color, any color

The disparate alert level systems have been another challenge, both internally and externally. The OSDH still publishes a county map based on an alert system that was essentially useless after early October, simply reporting Orange for months even as county cases more than quintupled and hospital intensive care unit capacity collapsed. The OSDE adopted a modified alert system and the OSSBA publishes a county map for it. As cases mounted over the winter, the OSDE system similarly lost its discrimination.

As the politically inconvenient winter surge worsened, Oklahoma’s governor deliberately stopped distributing White House Task Force reports, which had its own more discriminating alert levels and routinely offered advice which he ignored. For weeks, Oklahoma was a top three state in cases, positivity, and hospitalizations, and would have posted similarly high death rates, except that the OSDH knowingly failed to provide accurate and timely death counts for months. And its useless alert system stayed stuck in Orange statewide, since it was repeatedly altered to make it impossible to ever signal Red for a single county.

The CDC now has its own county data tracker with a “Level of Community Transmission” that was once part of the White House Task Force reports, and throughout the pandemic there have been popular systems from Covid Act Now and others with their own idiosyncratic alert levels.

An example of the conflicting signals and lack of discrimination for three of the most prominent alert systems in Oklahoma

This confusing array of conflicting alert levels remains problematic. Oklahoma’s Legislative Office of Fiscal Transparency found that “OSDH’s COVID-19 reporting fails to align with stakeholders’ needs” and “the data provided by the State was either lacking in substance, withheld, misaligned, or never developed for public consumption.”

Consequently, since August I have steadily refined my own tracking sheet of district, city, county, and state data. I update it daily to maintain my timeline charts of cases, vaccinations, regional hospital bed use, regional ICU bed use, state ICU bed availability, and the impact on our local hospital. All of that, along with our district’s student and staff cases and student and staff absenteeism have been shared publicly and reviewed weekly by our Pandemic Response Committee.

Where We Stand

Under the leadership of Dianne Martinez, Exec. Dir. of Elementary Schools, and Jason Langham, Exec. Dir. of Secondary Schools, our site principals and teachers have scrambled as conditions improved to adjust as full-time virtual students migrated back to in-person. The virtual student enrollment which peaked in early September at about 20% has now fallen to about 11%.

Thad Dilbeck, the Director of Athletics and Activities, has spearheaded the efforts of our many coaches and sponsors in adapting to changing safety restrictions and procedures throughout the pandemic.

Jon Beckloff, Sodexo Director of Child Nutrition, has displayed immense creativity, flexibility, and perseverance throughout the pandemic. Thanks to amazing work by his dedicated staff, with steadfast assistance from our transportation department, over 1,000,000 meals will have been served during the pandemic to our students and staff.

As I noted earlier, our student and staff cases collapsed this month. Seasonality and vaccinations have changed the character of the pandemic: everyone is outside more with the warmer weather, where viral particles are readily dispersed. As of April 8, a significant majority of our staff had achieved full vaccination. But we’re seeing a noticeable dropoff in new vaccinations across the state, and currently only about 20% of our county’s total population is fully vaccinated. Masking is on the decline in public venues around town. So we remain vulnerable to more infectious variants and superspreaders.

The improved conditions have allowed our committee to begin coupling our pandemic protocols to an alert level I will calculate. It uses the same color coding system adopted by the OSDE, but does not rely on the weekly rate of new positive cases for the county. Instead, I will calculate the city’s rate and, when feasible, average that with our rate of staff and student cases.

In recognition that conditions have changed, we are relaxing our face covering protocols so long as cases remain low, and we have relaxed usage of our staff screening app. Both of those protocols will escalate and de-escalate based on the alert level I will publish each Wednesday at BPSLEARN.COM.

The Trail Ahead

Here is the future I dimly see in my spiky crystal ball:

Here is the future I dimly see in my spiky crystal ball:

- The majority of students and staff will become increasingly careless and complacent this summer, despite occasional breakthrough infections, although a distinct minority of students and staff will continue to mask throughout the 2021-2022 academic year.

- We will have far fewer Distance Learning days in 2021-2022.

- We’ll see a surge of infections next fall and winter, probably rising to Orange 2, and Red is certainly possible. The infection rate will be far higher among the unvaccinated, with some breakthrough infections among the vaccinated, particularly those who travel extensively, attend large crowded indoor events, and never mask. Hospitalizations will also surge but will not be nearly as predictably coupled to cases as they were previously, with far lower actual death rates.

- Our full-time-virtual enrollments will likely be below 5%, although they could rise above that level during the winter whenever the surge becomes apparent.

- Our middle and high school students will be offered vaccinations this fall or early winter, but many, possibly a majority, won’t take advantage of them.

- Booster shots to better protect against variants of concern will become available this winter, and a majority of our district staff will get one.

Thus, for this summer and the 2021-2022 academic year, our committee will be working on coupling many more of our protocols to our district’s alert level. I expect to see distancing, contact tracing and quarantines, visitor restrictions, third-party use of our facilities, and which internal metrics we generate, along with face covering and staff screening requirements, to all fluctuate with the district’s calculated alert level.

In general, so long as we remain in the low Green or Yellow levels, our protocols will be more relaxed than what we had for most of the 2020-2021 academic year. But they will escalate at Orange Level 1 and, should we rise to Orange Level 2, most of them will be restored to what we became accustomed to this school year.

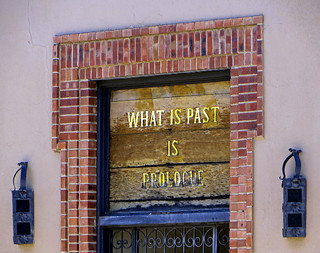

As the bard wrote, “…what’s past is prologue, what to come in yours and my discharge.”

I really appreciate your analysis here. It all makes such sense. Our family will continue to be cautious. And we’ll getting boosters as soon as they say we should! Thank you!