Clang, clang, clang went the trolley

Ding, ding, ding went the bell

Zing, zing, zing went my heart strings

From the moment I saw him I fell.

So sang Judy Garland in 1944’s Meet Me In St. Louis. Although my father rode an interurban trolley to high school up in rural Kansas, my own experience with trolleys is rather limited.

My only regular rides on a “trolley” were as an undergraduate at the University of Oklahoma, which began running the Boomerville “trolley” in 1980. It was made to resemble an old-fashioned trolley, complete with wooden interior seats, but ran around campus on rubber tires, not tracks, and was propelled by an internal combustion engine. There were a few of that style of trolley in the university’s system while I was there from 1984-1988, but they soon added regular coach buses, which I greatly preferred. They had far more comfortable seats and were air conditioned.

I have ridden one actual trolley, the Saint Charles Streetcar Line in New Orleans, which is the oldest continuously operating streetcar line in the world. I’ve seen the Old 300 trolley along the Columbia River in Astoria, Oregon. But I’ve never been to San Francisco, so I have not experienced its famous cable cars.

Real trolleys were once commonplace. Oklahoma City had an extensive system from 1903 to 1947, including interurban lines that stretched north to Guthrie, south to Norman, and west to El Reno. Oklahoma City brought streetcars back in 2018 on new tracks that make a couple of loops downtown, but if you want to experience a historic trolley, you need to go west to El Reno, where the Heritage Express Trolley runs a 1924 car on a 1.5-mile loop.

Tulsa once had three electric railway companies, with service starting in 1906 and peaking in 1923 with 21 miles of rails. An interurban ran to Sand Springs until 1955 and to Sapulpa until 1960.

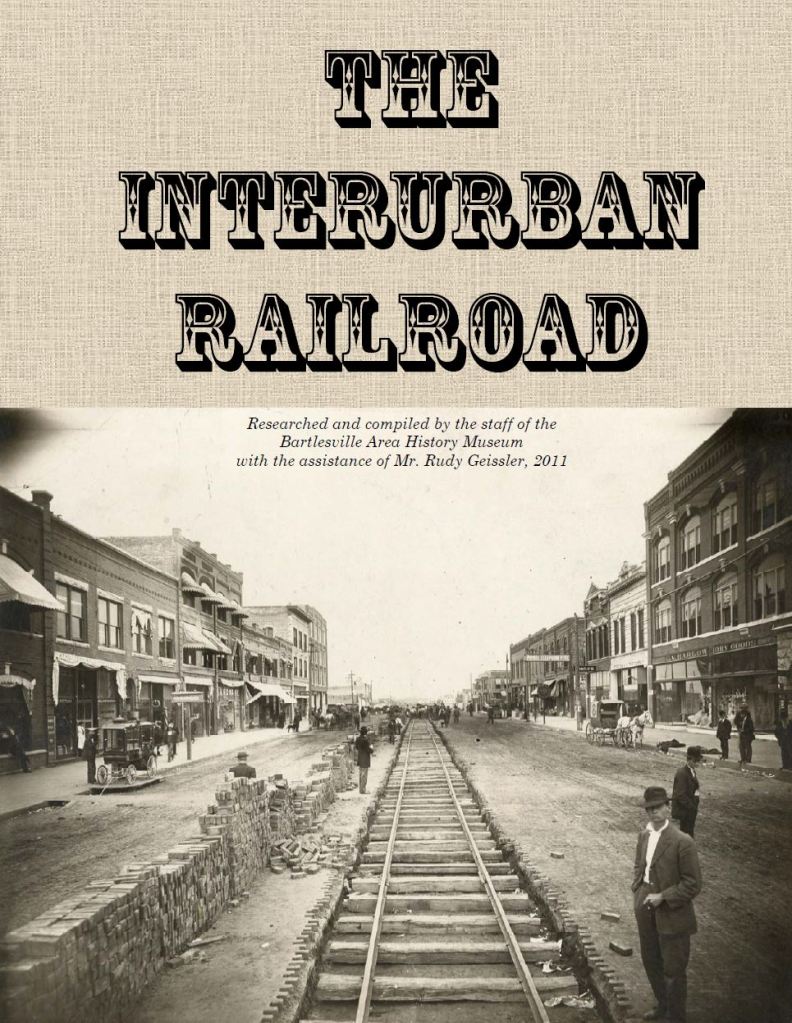

Even little Bartlesville had a trolley. From 1908 to 1920, there was an interurban that extended from Dewey down to the old smelters in southwest Bartlesville. A thorough history has been compiled by the Bartlesville Area History Museum.

I’ve posted here before about some of the remains of the interurban one can spot along the Pathfinder Parkway near Robinwood Park, and there is still a diagonal Interurban Drive northeast of the park that follows part of the old route that once led past the unincorporated Tuxedo community as it headed north to Dewey.

My father was born in Dewey several years after the interurban folded. But he still got to ride an interurban trolley in the years before World War II, because his family moved north to rural Kansas.

My grandfather had left farming in southwest Missouri in 1923, bringing his family to Dewey in a covered wagon pulled by a team of horses. His brother-in-law, Enoch Weston, was working as a power plant operator at the Dewey Portland Cement Company, and my grandfather hoped to land a job there.

After a considerable wait, he was hired at Dewey Portland, starting out in the foundry and later becoming a machinist in the plant’s machine shop. In 1936, my grandfather got a job as a machinist for the Cities Service Gas Company. Although Cities Service was headquartered in Bartlesville, and would not leave it until 1968, the job site was an isolated compressor station up in Kansas.

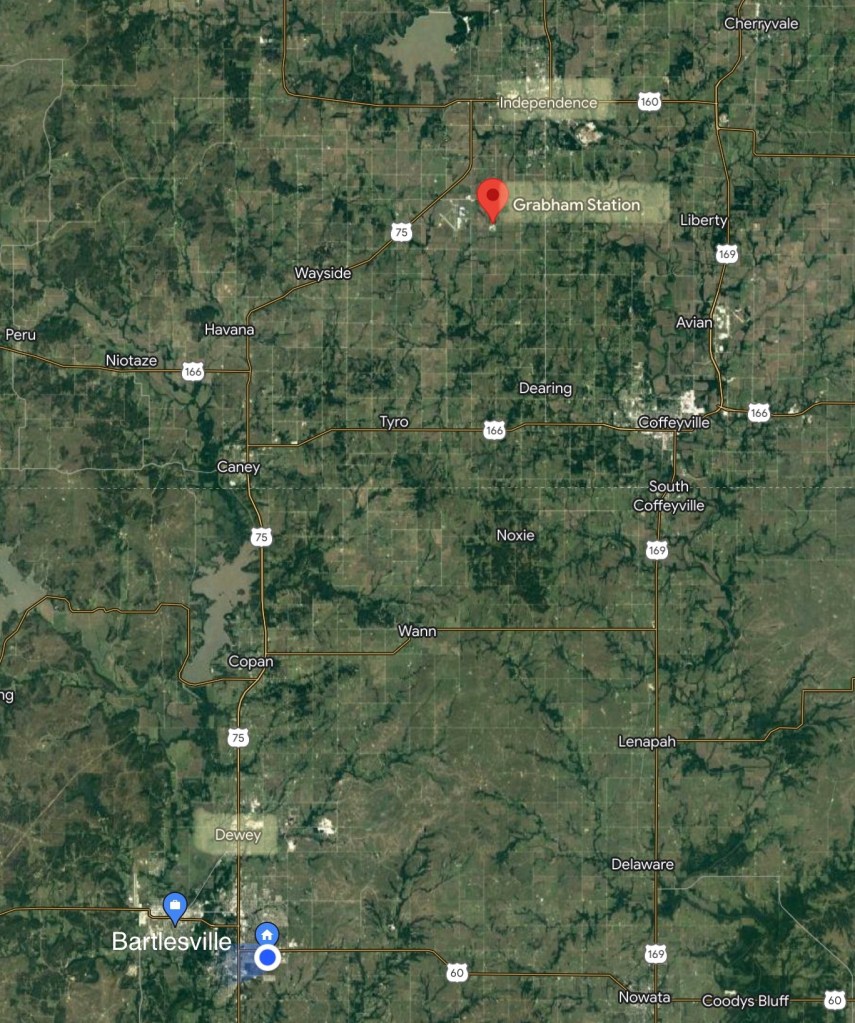

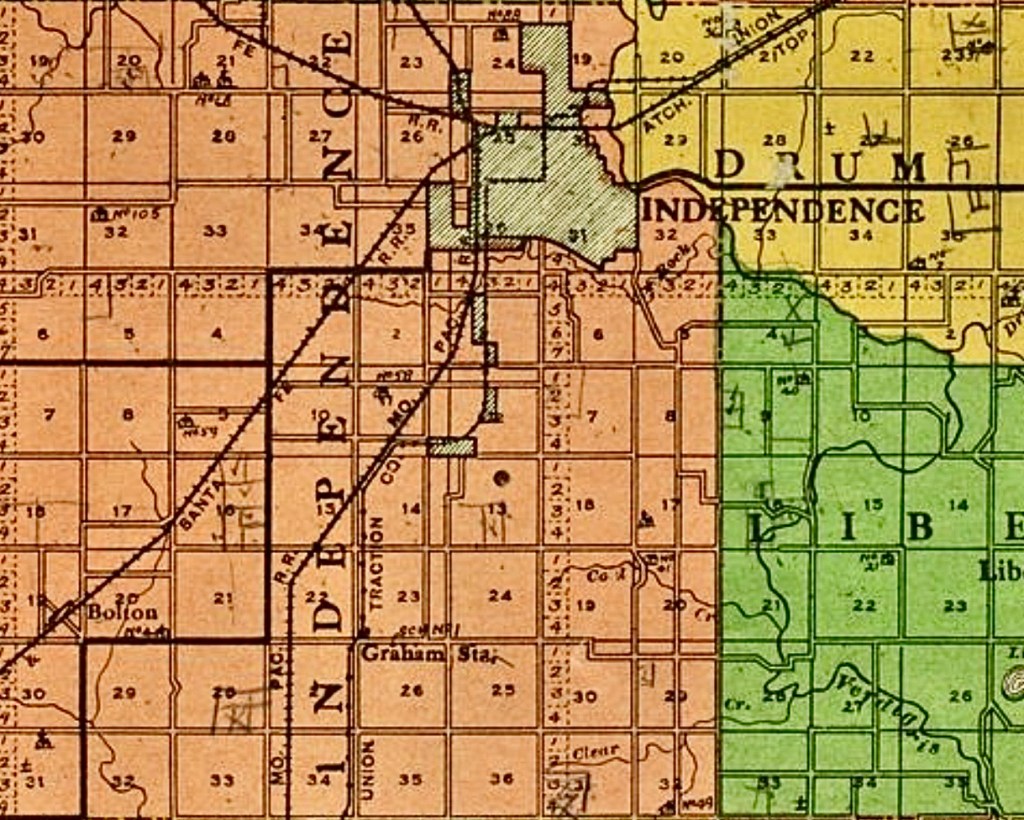

The family moved 27 miles northwest as the crow flies, and maybe 35-40 miles by road, to Grabham Station about five miles southwest of Independence. Dewey was a small town, small enough that the Meadors once packed into their Studebaker Erskine on Saturday nights to drive four miles to Bartlesville to shop and people watch. But Grabham Station wasn’t even a town.

The station compressed natural gas to send it down pipelines to various cities and industries. A pipeline division was stationed there, along with a pipe yard and welding shop. There were about 20 company houses at the station, which employees rented at a modest rate of about $2 per room per month.

I got to know those old houses pretty well, since when he retired, my grandfather purchased two of them and moved them nearer to town and Independence Community College. Those houses were where my grandparents and one pair of my aunts and uncles lived when I was a kid.

My father attended 7th and 8th grades at the Maple Grove one-room schoolhouse about a quarter-mile from the station. As you might guess from the above photos, Dad said there sure wasn’t any grove of maple trees around the school when he attended.

Dad was a pretty smart cookie, being named the 8th grade salutatorian among the 176 rural school 8th graders in Montgomery County. He posed for his 8th grade graduation photo in his first suit.

More to the point for this post, his graduation meant that it was time for him to leave the one-room schoolhouse for high school in Independence.

He could have ridden his bicycle, as he often did in good weather for the quarter-mile to Maple Grove. But to reach Independence, he would have to travel two miles east on a gravel road to then take the paved 10th Street five miles north into town. He only did that a few times, since it was far easier to ride the interurban.

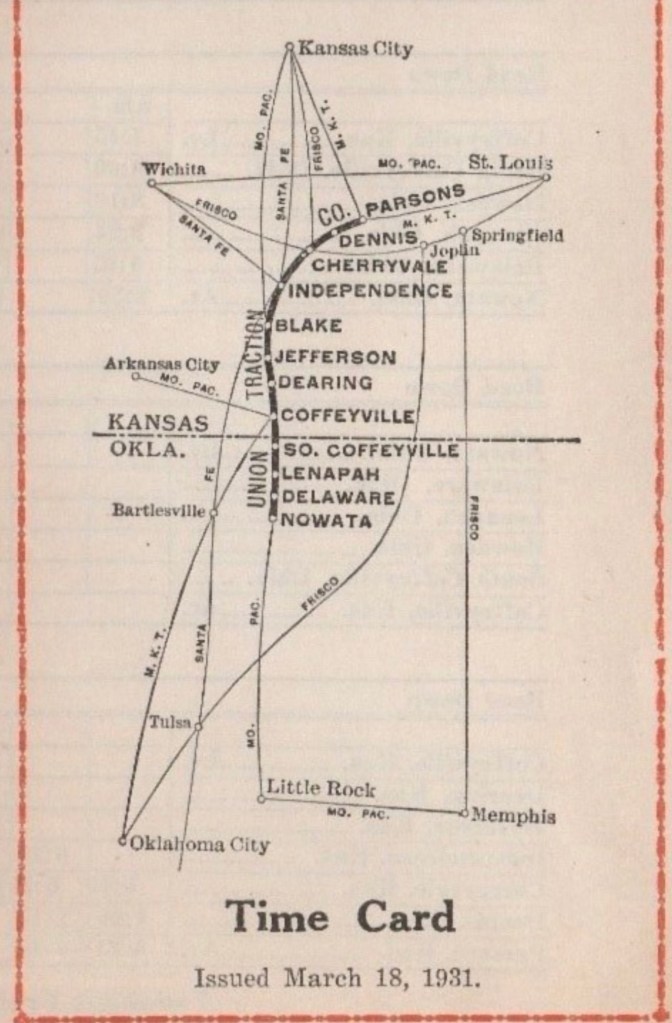

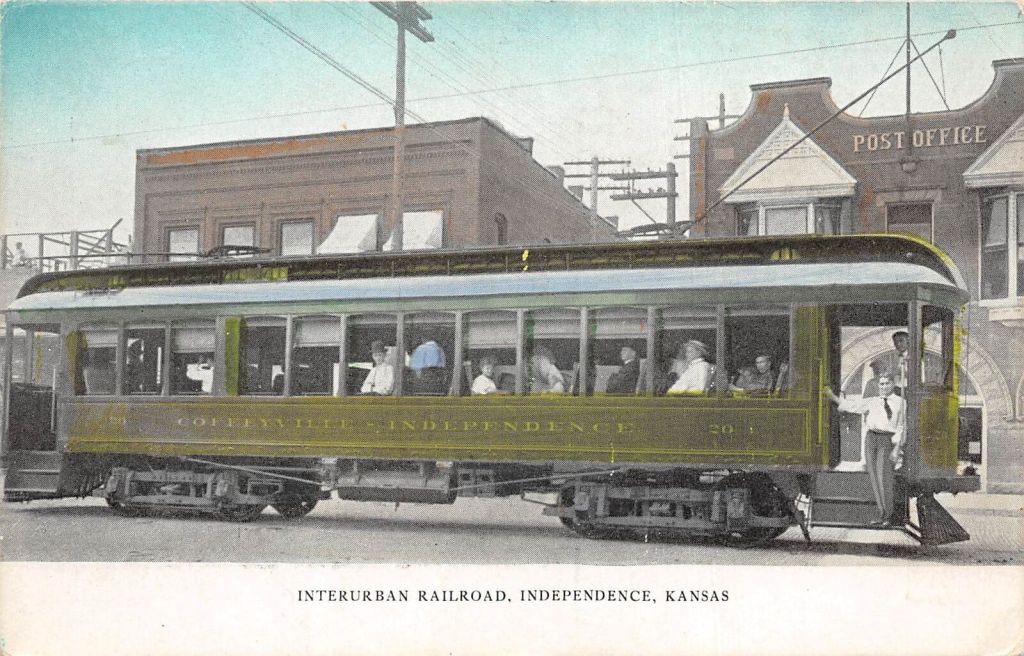

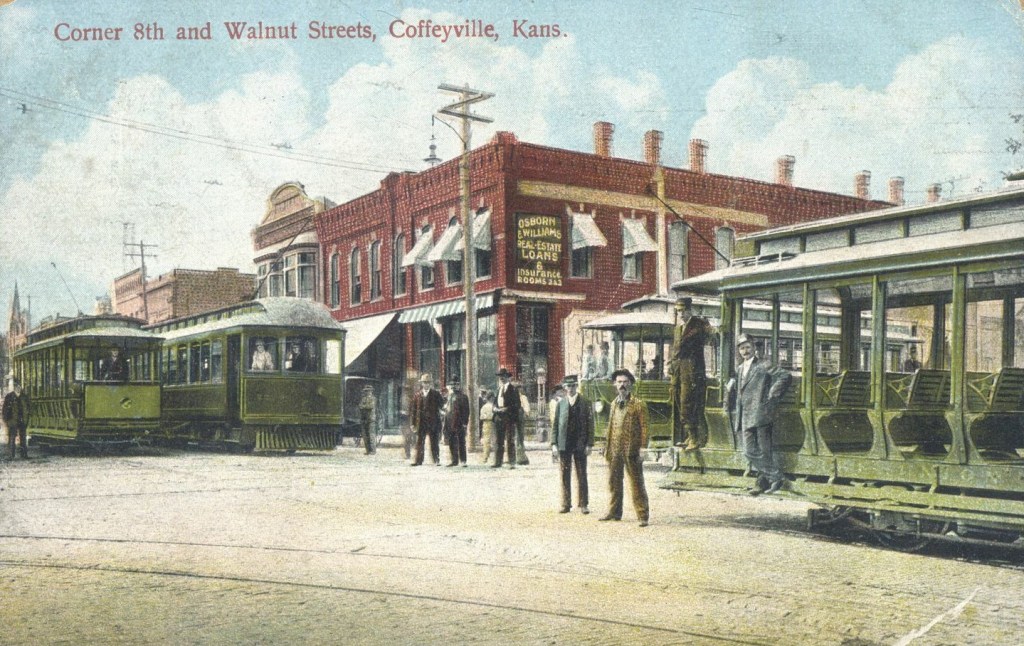

The Union Traction Company was created in 1904 and initially linked Coffeyville, Independence, and Cherryvale, Kansas. By the 1930s it had grown to reach 88 miles from Parsons in the north down to Nowata in Oklahoma. It ran right past Grabham Station, and remained in operation until 1947.

My father wrote:

The rural kids that rode this electric trolley were pretty rowdy at times. A small portion at the rear of the car was closed off from the rest of the car. This rear section was called the “smoker” because that was where smoking was allowed. Isolated as it was from the motorman, it became a favorite area for the “wild bunch” to gather. There was lots of cutting up and loud noise back there. A favorite trick to pull on the motorman was for several boys to get off at one stop and, as the trolley pulled away, one of the boys would run behind the trolley and pull down the mast that rode the hot wire above the car. This disconnected the electric power to the car and stranded it. The poor motorman would have to get out and re‐engage the power mast before the car could move on down the track. Of course the boys would have scattered by then and the poor motorman would not be able to tell which one was the culprit. Don’t you know it took a lot of patience to be a motorman?

Dad would ride the interurban throughout high school, including for jobs at a couple of grocery stores and a year of junior college, until he was inducted into the U.S. Army in 1943. After service in Denver, Europe, and the Philippines, he returned to Independence before enrolling at Kansas University in Lawrence. He didn’t own a car until he bought a 1930 Chevrolet coupe in 1946. I like a story he told about that first car:

It only ran part of the time. I say that because it had a bad habit of suddenly quitting as I was driving along. I found that by getting out and raising the hood, disconnecting the gas line from the carburetor, back blowing the line to the gas tank by using my tire pump, connecting the line back, and closing the hood, I could be on my way once more. Needless to say, when this occurred in traffic it was not only irritating but quite dangerous.

The problem was solved by my fishing a large silk or rayon rag, that had long streamers of thread along its edges, from the gas tank. The streamers had been periodically floating into the opening to the gas line and stopping the flow of gas to the motor. Problem solved!

Later a valve broke off and exited through the side of the engine block. My father haggled with a shade tree mechanic to replace the valve and braze shut the hole for $35, which he said made the car worth at least $45 at that point! He ended up borrowing $435 from his father to buy a 1929 Ford Model A coupe that served him better for a couple of years.

Despite the hassles of owning and maintaining an automobile, the shift from streetcars to private automobiles was commonplace, with few trolleys surviving for long after World War II. We tend to romanticize trolleys, but most towns are now designed around the automobile, ensuring its continued dominance. Streetcars are now just a rare novelty, and interurbans a distant memory.

Buzz, buzz, buzz went the buzzer

Plop, plop, plop went the wheels

Stop, stop, stop went my heart strings

As he started to leave

I took hold of his sleeve with my hand

And as if it were planned

He stayed on with me and it was grand just to stand

With his hand holding mine to the end of the line.

Hi. I like the little bit of history about the interurban. It adds to what I can remember my uncle telling me. He could very well have been that motorman you mentioned. He worked for Union Electric Traction Company until they transitioned to diesel busses in 1947. I remember watching an old 8mm home movie on YouTube taken on the very last run. It was interesting to see what some of the towns looked like back then. At least the ones that are still there. I don’t remember if your dad’s stop was shown or not. If you want more information please feel free to contact me. duanetull@yahoo.com