It took me 50 years to finish reading Pinocchio. For decades, I blamed Walt Disney and Charles Folkard for that tardiness: Disney for the false impression his 1940 film gave of the book it animated, and Folkard for a book illustration that backfired.

1971

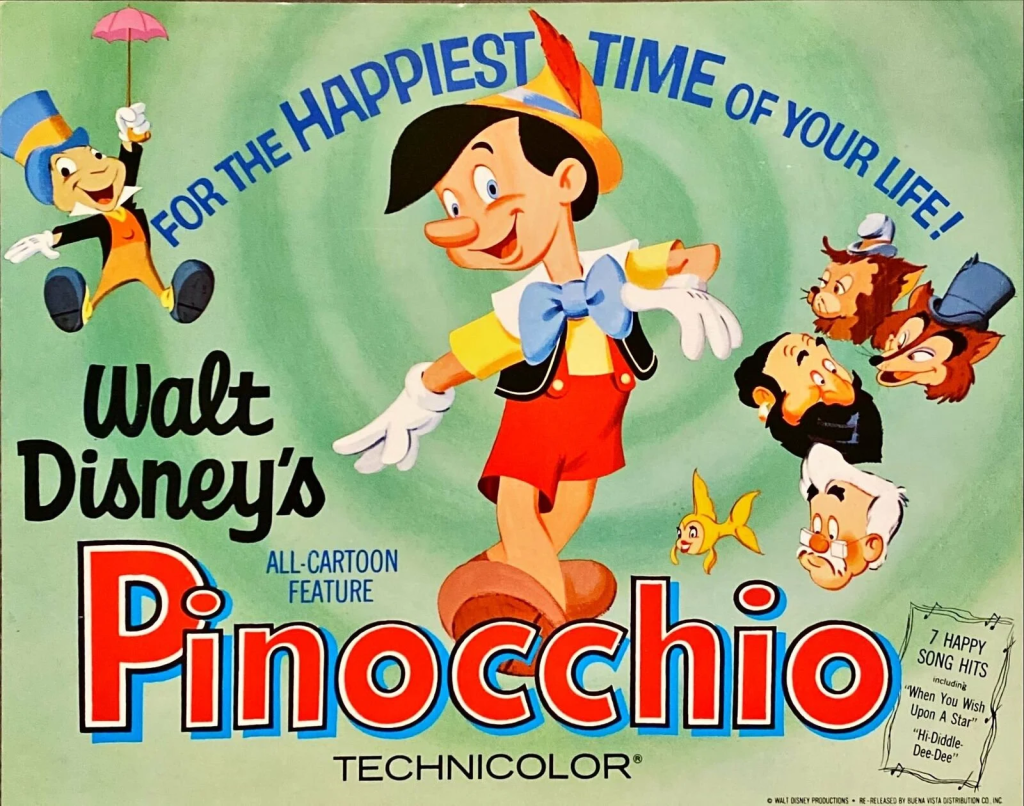

My tale begins in 1971, when I was turning five years old. Walt Disney’s 1940 musical fantasy film based on the 1883 novel was re-released that summer. I greatly enjoyed the film, and I never forgot how Pinocchio and his friend, Lampwick, misbehaved on Pleasure Island and were turned into donkeys after making “jackasses” of themselves. I clearly remembered Pinocchio and his maker, Geppetto, being trapped inside a whale and escaping by making it sneeze. And of course I remembered Jiminy Cricket, how Pinocchio’s nose grew when he told lies, and When You Wish Upon A Star.

Despite its later status as an animation classic, the film was not a box-office success when it was released in 1940. It had cost $2.6 million to create, not including promotion and distribution, and raked in less than $2 million. Walt Disney was quite depressed when both Pinocchio and Fantasia flopped in 1940, although he could take some comfort in the former winning Oscars for Best Original Score and Best Original Song.

My aborted childhood attempt to read the novel

I was precocious, reading 135 books in first grade. So a couple of years later my parents gave me a hardbound edition of the Pinocchio book. It had an orange cover and had been printed by Grosset & Dunlap decades earlier. I suspect my father picked it up at a garage sale.

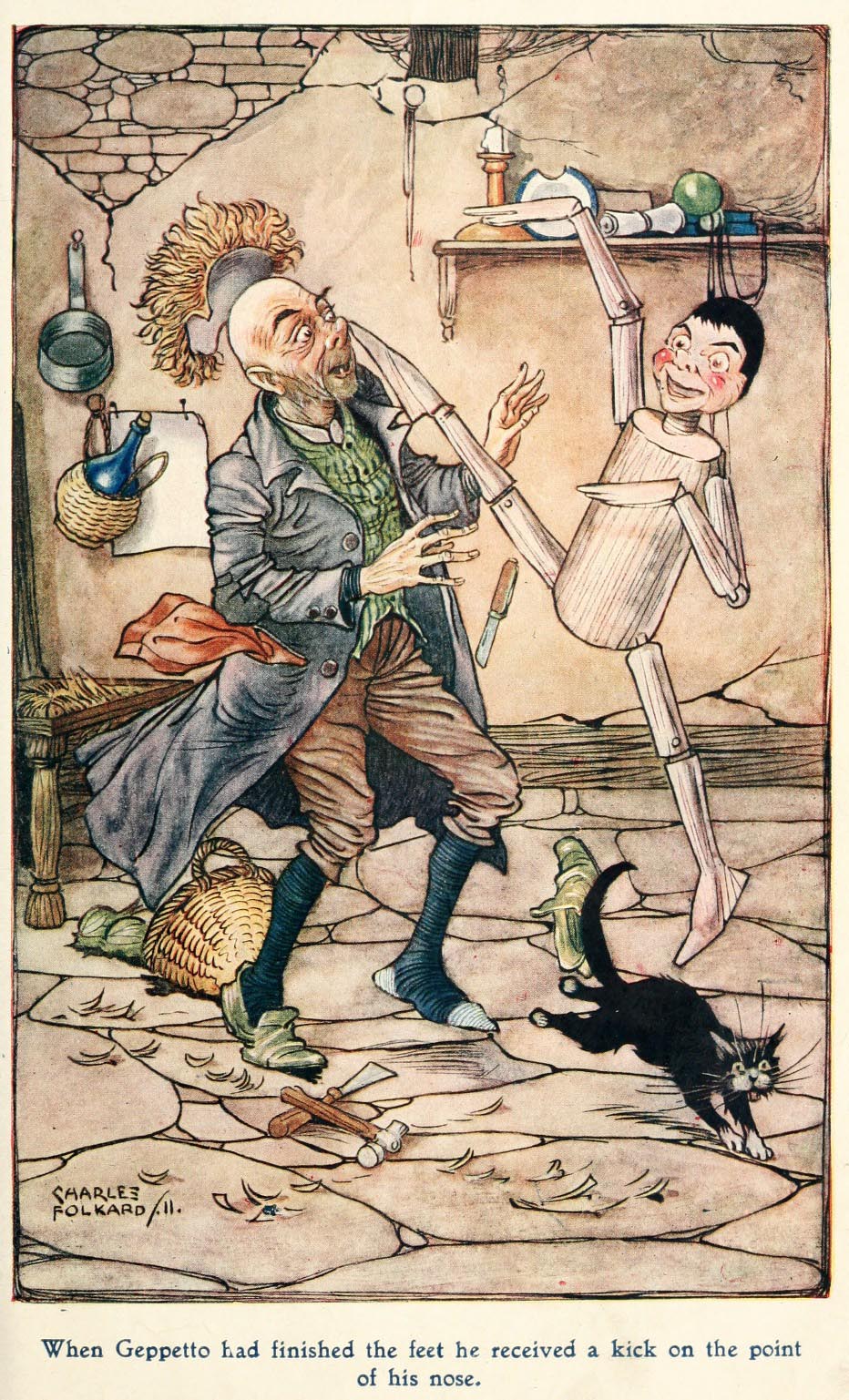

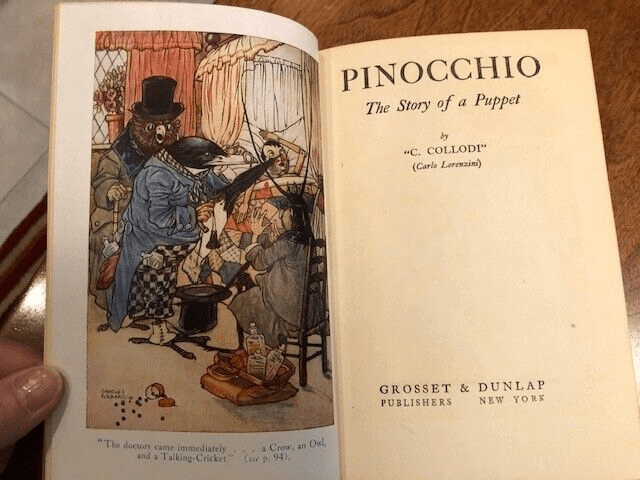

I remember opening the 200-page book and being surprised that it was a novel, not a simple illustrated book. I was then thoroughly unnerved by the only illustration in it, which was right before the title page. It showed an owl, a crow, and a disgusting-looking anthropomorphic cricket examining a marionette lying in a bed. That marionette looked nothing like the Pinocchio I had seen in the film.

With Italy a fascist state that joined World War II as one of the Axis Powers in 1940, Disney had chosen to emphasize a Tyrolian setting in the Alps of northern Italy and western Austria for his film. His version of Pinocchio was a fat-cheeked little guy who meant well and wore a little alpine hat with a feather, a far cry from the novel’s skinny, weird-looking jerk who wore an outfit made of flowered paper, shoes made from tree bark, and a little hat from the soft part of a piece of bread.

I was particularly upset by the Talking-Cricket doctor in Folkard’s illustration. Was that hideous half-human half-insect thing supposed to be Jiminy Cricket?

I didn’t know it, but Pinocchio had originated in 1881 as the serial La storia di un burattino in the Italian weekly children’s magazine Giornale per i bambini. Carlo Lorenzini, writing under the pen name of Collodi, stopped his first series at Chapter 15 later that year. But a few months later, popular demand convinced him to extend it to 36 chapters, and he published the complete story as a single book in 1883, with illustrations by Enrico Mazzanti.

The text of my edition was the first English translation of the novel, performed by Mary Alice Murray in 1892. My cheap edition only included that single color illustration, created in 1910 by Charles Folkard for a British publisher. Decades later, I found out that Folkard had created several full-page watercolor illustrations for the novel, along with dozens of line drawings sprinkled throughout far better earlier editions.

Despite my misgivings from that single disturbing illustration, I screwed up my courage and began reading the novel. The deviations in the film were immediately apparent, throwing my young mind for a loop. The novel began with Master Cherry the carpenter, not Geppetto, cutting on a talking piece of wood. Geppetto did not appear until the second chapter, and the two characters became angry and “from words they came to blows, and flying at each other they bit, and fought, and scratched manfully.” Egad!

Geppetto soon carved the “puppet” Pinocchio from the talking piece of wood, with no talk of wanting a little boy, no blue fairy, etc. Rather than living in a shop full of clever clocks, he was so poor that all his room had was a worn-out chair, a crummy bed, a derelict little table, and on the far wall a painted fire.

I remember being confused as a child when the book and the film referred to Pinocchio as a puppet, when he was obviously a marionette. The 2021 annotated translation by John Hooper and Anna Kraczyna reveals that Collodi used the word burattino throughout the novel, which was used loosely at the time to describe both puppets and marionettes. Only once did he choose to refer to Pinocchio with the actual term for marionette.

I made it through Chapter IV, when the “Talking-cricket” appeared. But I was shocked by how it ended:

‘Poor Pinocchio! I really pity you ! . . . ‘

‘Why do you pity me?’

‘Because you are a puppet and, what is worse, because you have a wooden head.’

At these last words Pinocchio jumped up in a rage, and snatching a wooden hammer from the bench he threw it at the Talking-cricket.

Perhaps he never meant to hit him; but unfortunately it struck him exactly on the head, so that the poor Cricket had scarcely breath to cry cri-cri-cri, and then he remained dried up and flattened against the wall.

And that was where I stopped reading for 50 years: Pinocchio killing the character I knew as Jiminy Cricket.

Five decades later…

In January 2024, the copyright on Disney’s 1928 cartoon Steamboat Willie finally expired. That was news, since it meant that the first version of Mickey Mouse was finally in the public domain. I was never interested in Mickey, but the publicity got me thinking about Disney and copyright law.

Back in 1790, copyrights in the USA only applied to maps, charts, and books for up to 28 years. In 1831, that was lengthened to 42 years and extended to musical compositions, but not performances. In 1909, that was lengthened to 56 years and extended to motion pictures.

In 1976, copyrights were extended to the lifetime of an author plus 50 years, and to 75 years from publication for prior works-for-hire created for corporations, in keeping with the Berne Convention, an international copyright treaty. That would have finally ended the copyright on Steamboat Willie in 2003, so in 1998 Disney helped get the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act into law, which extended it to the life of the author plus 70 years and to 95 years for works created by corporations.

It was, of course, hypocritical of Disney to lobby for such extensions to protect its own works, given that many of them were based on prior works which had fallen out of copyright. If the copyright law Disney successfully promoted in 1998 had applied to the original Pinocchio novel, Walt could not have made his 1940 film without permission and licensing from the estate of Carlo Lorenzini, since the novel would have remained under copyright until at least 1960.

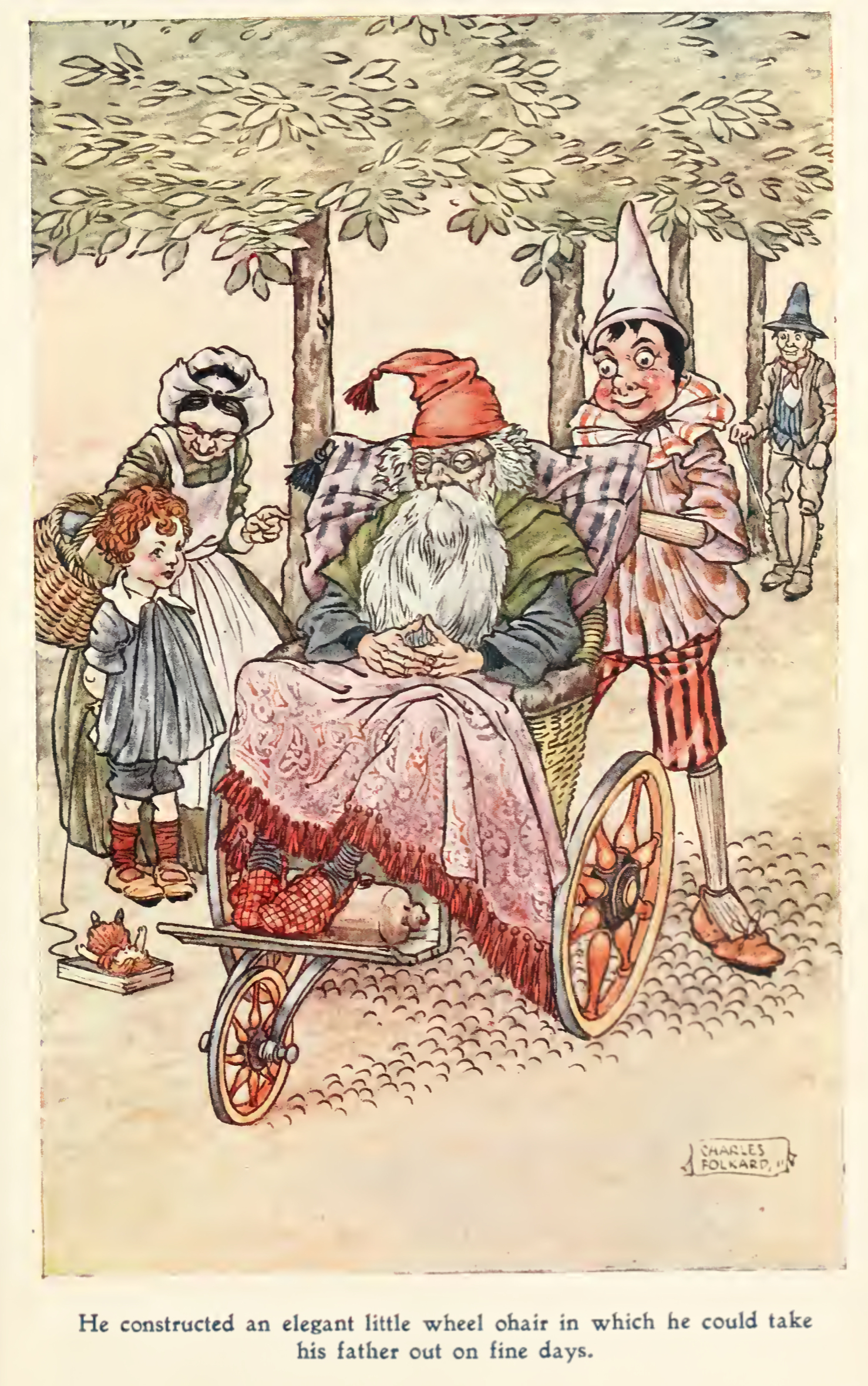

That was bouncing around my brain when an arctic blast had me working virtually from home for three days. That return to my work life during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic reminded me of relaxing videos I had enjoyed during the stressful pandemic, such as Pete Beard’s videos on illustrators. One of his early videos had included Charles Folkard.

That was enough to prompt me search out Folkard’s other watercolor and gouache illustrations for Pinocchio.

I could tell some of the scenes had been adapted into the Disney film, but several had not. So I decided to finally finish reading Pinocchio. I no longer owned the old hardback copy of my youth, which was just as well given its paucity of illustrations. So I ordered two print editions: a Golden Books for Children edition from 1920 that included Folkard’s illustrations, and a 2004 edition with illustrations by Roberto Innocenti. I didn’t bother downloading older editions of the book with original illustrations by Mazzanti, as those did not appeal to me.

Then I decided to write this blog post about the experience, and regular readers will know that usually prompts me to do a considerable amount of research. So I purchased the Kindle edition of the splendid 2021 annotated translation by Hooper and Kraczyna. Footnotes can be a pain in a paper book or on a dedicated Kindle device, but they are quite usable in the Kindle app on an iPad. You can simply tap the footnote number to overlay it on the bottom of the page, which you can read and then tap to dismiss.

Surprises

If you are unfamiliar with the classic Disney film and/or the novel, Jon Solo to the rescue. He has made over 200 videos about the origins of children’s tales, and here is his complete summary of the plots of the 1940 Disney film and the novel:

One thing that was immediately apparent when reading the novel was what a rascal Pinocchio was. He could be mean-spirited and irresponsible, and he suffered mightily for it. His legs were burned off, and he almost burned alive as firewood.

I enjoyed him meeting the fox and the cat, with the former pretending to be lame and the latter faking blindness. They reminded me of Mark Twain’s twin grifters in Huckleberry Finn, the duke and the dauphin.

Pinocchio is shown to be truly naive, an easy mark, in contrast to how quickly Huck Finn figured out the ruses of the pair of crooks he encountered. Collodi was imparting lessons for children living in the impoverished rural areas of the recently-united Italy. Mandatory schooling was gradually being extended, and he repeatedly arranged for evil consequences when Pinocchio shirked school.

The story does not begin as a fairy tale. The famous Blue Fairy, who appears early on in the Disney film as a blonde in a blue dress and brings the marionette to life, doesn’t appear in the novel until the end of its first part, and then as the unexplained ghost of a little dead girl, waiting for her coffin to arrive.

Many translations call her the Fairy with Turquoise Hair, but Hooper and Kraczyna state that is incorrect. The novel uses the term turchino, which means dark blue, not turchese, which would be turquoise. It was believed that her later and older incarnation in the text was based on blue-eyed Giovanna Ragionieri, who was a young teenager when the book was being written. But her initial introduction is dreamlike and frightening, perhaps partly based on a memory of the author’s sister Marianna Seconda, who died at age six. Death was familiar to Lorenzini: five of his nine siblings died before reaching the age of seven.

That familiarity with death and intense suffering led Collodi to pull few punches in the early chapters. The original series of stories ended tragically with Chapter XV. Here is how Mary Alice Murray translated the cruelty of the barely disguised cat and fox, who want the remaining gold coins Pinocchio has hidden in his mouth:

‘Let us hang him!’ repeated the other. Without loss of time they tied his arms behind him, passed a running noose round his throat, and then hung him to the branch of a tree called the Big Oak. They then sat down on the grass and waited for his last struggle. But at the end of three hours the puppet’s eyes were still open, his mouth closed, and he was kicking more than ever.

Losing patience they turned to Pinocchio and said in a bantering tone: ‘Good-bye till to-morrow. Let us hope that when we return you will be polite enough to allow yourself to be found quite dead, and with your mouth wide open.’ And they walked off.

In the meantime a tempestuous northerly wind began to blow and roar angrily, and it beat the poor puppet as he hung from side to side, making him swing violently like the clapper of a bell ringing for a wedding. And the swinging gave him atrocious spasms, and the running noose, becoming still tighter round his throat, took away his breath.

Little by little his eyes began to grow dim, but although he felt that death was near he still continued to hope that some charitable person would come to his assistance before it was too late. But when, after waiting and waiting, he found that no one came, absolutely no one, then he remembered his poor father, and thinking he was dying . . ., he stammered out: ‘Oh, papa! papa! if only you were here!’

His breath failed him and he could say no more. He shut his eyes, opened his mouth, stretched his legs, gave a long shudder, and hung stiff and insensible.

Jeepers! The influence of the Christian gospels is clear, as is the warning about boys who disobey their fathers. If the tale had ended there, as originally intended, I question if it would have become a classic.

There is a clear change in the storytelling after that point. It reads much more like a fairy tale, with the dead blue-haired little girl, who occupied a small house in the woods, eventually becoming an adult fairy who lives in a mansion. She intercedes to save Pinocchio and, after many more travails and his final redemption, changes him into “a smart, lively, beautiful child with brown hair and blue eyes who was as happy and joyful as a spring lamb.”

The moralizing tone is far more noticeable in the second part of the book, which introduces Pinocchio’s most famous characteristic, a nose that grows when he lies. But he also tells at least six notable lies that have no effect on his proboscis, so it is not a consistent consequence.

Another Biblical parallel in the latter section of the book is when Pinocchio finds Geppetto inside a large sea creature. I was interested to find that Collodi did not make it a whale. He knew that most whales had large mouths but their throats were too small to swallow a person. He made the creature a shark, a pescecane, in a likely reference to loan sharks, which were described in Italy as pescecani. Collodi’s own father had fallen into the clutches of a usurer, and Collodi went into debt to assist him. So, as Hooper and Kraczyna put it, “…father and son both experienced what it was like to end up in the ‘belly of the shark.'”

While the Talking-cricket, Pinocchio, and the blue-haired girl are each reincarnated in different ways, some miscreants end badly. The cat ends up going blind for real, and the fox goes from pretending to be lame to suffering from ringworm and paralysis, forced to sell his tail to be made into a salesman’s fly whisk. Pinocchio answers his murderers’ pleas with a series of proverbs:

Stolen money never bears fruit.

The devil’s flour all turns to bran.

Those who steal their neighbor’s cape usually die without a shirt.

And then there is Lampwick, Pinocchio’s friend who lured him to abandon school to spend months of leisure at Playland. They caroused and played games until catching donkey fever, but the novel does not depict them smoking, drinking, and fighting like the Disney film has its bad boys doing on Pleasure Island. For once, Disney’s version is nastier than the novel, but the film does not depict Lampwick’s ultimate fate after his transformation into a jackass.

In Chapter XXXIII of the novel, the narrator says he does not know the fate of Lampwick. But in the final Chapter XXXVI Pinocchio finds Lampwick:

As soon as Pinocchio entered the stable, he saw a pretty little donkey lying on the straw, all skin and bones from hunger and overwork. After he had had a careful look at him, he became deeply troubled and said to himself: “But I know that little donkey! His face isn’t new to me!” And kneeling down close to him, he asked in donkey dialect: “Who are you?” In response, the little donkey opened his dying eyes and, stammering in the same dialect, answered: “I’m Lamp . . . wick . . .” Then he closed his eyes again and breathed his last.

So the novel retains some bite even with its metamorphosis into a literal fairy tale. The contrast between how Pinocchio treats the Talking-cricket early on and Lampwick at the end certainly illustrates his character growth.

The novel continued to surprise, even to its last lines. When Pinocchio finally turns into a boy, he kisses Geppetto and asks, “And where do you think the old wooden Pinocchio has gone?”

“There he is — over there!” replied Geppetto, and he motioned toward a large puppet that was propped up in a chair, his head turned to one side, his arms dangling and his legs crossed and bent at the knees. It seemed miraculous that he could stay upright.

Yikes! So the marionette wasn’t transformed into a boy. Rather the consciousness once trapped in a piece of wood was transferred into a freshly created boy. If I were Pinocchio, I’d be having quite the existential crisis at that sight.

It is that repeated disturbing strangeness, the perplexing weird nature of the novel, that makes me glad that I finally finished it after a gap of over a half-century. Was it worth the wait? Sì.

Disney made a TV musical called “Geppetto” in 2000, in which an all-star and largely-Star-Trek cast shows Geppetto’s character growth from a childless single man who thinks parents are unworthy of their kids to an unexpected single parent who thinks his son is unworthy of him to a loving father at last. The scenarios contrived by the Blue Fairy to teach him lessons are jaw-dropping — in that they could so easily have gone horribly wrong — and the songs are really pretty good, but the production is cheesy verging on camp. The version of Pleasure Island presided over by Usher (!) is… like a fabulous gay bar for underage boys? Questionable choices were made. But it has a good message for us childless adults about the pitfalls of parenthood!