Polly Hotchkiss, Field Enterprises Educational Corporation representative #5592514, was 46 years old when she made the sale. It was March 9, 1968 when she convinced a 31-year-old mother in the Western Village neighborhood of Oklahoma City to invest $228.35, to be paid in three monthly installments, for a 20-volume set of the World Book encylopedia. It was bundled with a 15-volume set of Childcraft books for the mother’s 19-month-old son.

That was a hefty purchase, translating to over $2,000 in 2024 dollars, and my mother paid it in three monthly installments.

I would grow up consulting the Childcraft books, which had simple text and illustrations designed to make learning fun. It had these categories:

- Poems and Rhymes

- Stories and Fables

- World and Space

- Life Around Us

- Holidays and Customs

- How Things Change

- How We Get Things

- How Things Work

- Make and Do

- What People Do

- Scientists and Inventors

- Pioneers and Patriots

- People to Know

- Places to Know

- Guide for Parents

Here’s a sample page from volume 4, with an illustration by Charley Harper:

Although our set proclaimed Our 50th Year on their covers, Childcraft books actually dated back to 1934; the proclamation referred to the origin of the World Book by the same company. Chicago publishers J. H. Hansen and John Bellow had enlisted Michael Vincent O’Shea, a professor of education at the University of Wisconsin, to help them create it in 1917. Editor O’Shea wrote in the preface, “encyclopedias are apt to be quite formal and technical. A faithful effort has been made in the World Book to avoid this common defect.”

Field Enterprises, which had been founded by Marshall Field III, the founder of the Chicago Sun newspaper, purchased World Book in 1945. At one time, it employed over 40,000 salespeople who sold the encyclopedias door-to-door to families across the country, including one Polly Hotchkiss.

By the time I was in fifth grade, I had been making extensive use of the World Book, and my parents took advantage of the offer to exchange the 1968 volumes for new ones at a discounted price anytime from five to ten years after the initial purchase. On September 25, 1976 they paid $152.49 in three monthly installments, which would be over $800 in 2024 dollars. That was about a 50% discount.

I remember being impressed by the human anatomy transparencies in one of the new volumes, where you could build up figures layer by layer.

The informal style of World Book suited me well. But by junior high, I recognized its limitations. So I tried to consult the more prestigious Encyclopædia Brittanica in our junior high library, but I was annoyed by its three-part structure: the Micropædia of short articles, the Macropædia of long articles that might run anywhere from 2 to 310 pages, and a Propædia outline volume.

Speaking of the Britannica, my wife, Wendy, won a set of them a decade later in 1990, when she was a 14-year-old from tiny Eustace, Texas. Wendy won The Dallas Morning News Regional Spelling Bee. Being the best speller among over 10,000 students who competed in spelling bees across 700 schools in northeast Texas scored her the $1,600 set of books, which would be over $3,800 in 2024 dollars.

And yes, she was fascinated by the same sort of anatomical transparency overlays in her set of encyclopedias!

Before she won the Brittanica, Wendy’s family had the Funk & Wagnalls encyclopedia, which they had bought on an installment plan. But printed encyclopedias were soon facing stiff competition…on optical discs.

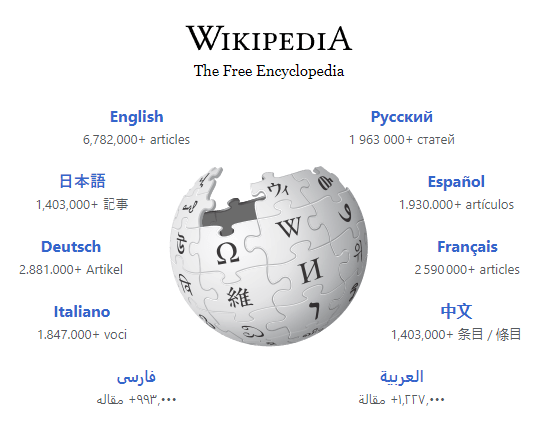

Compton’s put out a multimedia encyclopedia on CD-ROM in 1989, and in 1993, Microsoft launched its Encarta CD-ROM, which was initially based on Funk & Wagnalls after Britannica refused to partner with them. Britannica was in financial difficulties by 1996 and was bought out. Encyclopedias began moving online and by 2004, the free, online, and crowd-sourced Wikipedia was the world’s largest. Encarta itself only lasted until 2009.

Britannica‘s last print edition was in 2010, concluding 242 years of printed publication. World Book still had 45,000 door-to-door representatives in the late 1980s, but sales plunged, and it shifted its focus to selling sets to libraries. As of 2024, the only place they sell their printed set is online, with it consisting of 14,000 pages across 22 volumes, for $1,200.

Why someone would purchase a printed encyclopedia with 17,000 articles versus just using Wikipedia for free, which has almost 6.8 million articles, is beyond me. I presume some are still concerned about the accuracy of the world’s greatest encyclopedia, but this article shows such concerns are overblown.

I love Wikipedia enough that I donate $2.85 each month to support it. I consider that a great deal: I could pay it for the rest of my life and still not match, after adjusting for inflation, what my parents spent in 1968 and 1976 on the World Book. What price do we put on having the world at our fingertips?

P.S. For a fascinating overview of the history of encyclopedias, including Wikipedia, plus far more from museums to kindergarten classes, I heartily recommend the audiobook of Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge from Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic by the polymath Simon Winchester.

Oh the memories of actually feeling the pages and reading for hours. How spoiled we have become with keyword searchable text at our fingertips. Thank you for sharing.

Debbie Neece – Collections Manager Bartlesville Area History Museum 401 S. Johnstone Avenue Bartlesville, OK 74003 (o) 918-338-4292 (c) 918-914-0994

Be mindful of leaving history better than you found it! I am a history hoarder…it is an illness.