For some time I have been mining my family’s photographic archive for weekly remembrances which I post on Facebook and sometimes expand into posts on this blog. There have been times that I recalled that there was an old home movie clip that would help illustrate a post, but most of those were still trapped on old 8 mm film.

That prompted me to pull out my father’s film projector and screen and the reels of silent standard 8mm films he shot from 1961 to 1979. I had last viewed some of them 15 years earlier in Christmas 2009 when a storm left me snowbound with my parents in Oklahoma City over Winter Break.

Back then, I’d projected the films onto their old portable screen, using a digital camera to record the two films I had shot in junior high with Dad’s 1961 Kodak camera, along with a few clips from other reels he had shot. I decided I would try to digitize the remaining footage.

I set up the screen, put the projector on our ironing board, had a tripod ready for my iPhone, and threaded through the projector the last reel of film that my father had spliced together back in the 1970s. Wendy killed the lights, I flipped the switch, the motor ran, the film advanced, and the bulb glowed…for about a second. Then it blew out.

The Bolex

In August of 1963, three years before I came along, my father plunked down over $160, which is over $1,600 in 2024 dollars, at Pipkin Photo Service at Penn Square in Oklahoma City to purchase a Paillard Bolex 18-5 projector.

Paillard was a Swiss firm that made high-quality equipment: its cameras were used by famous directors like Steven Spielberg, Peter Jackson, Spike Lee, Ridley Scott, and David Lynch when they were starting out. That said, Dad’s little home movie projector began running slow in 1965, and my father paid Pipkin $40 to have it repaired at the factory in Switzerland.

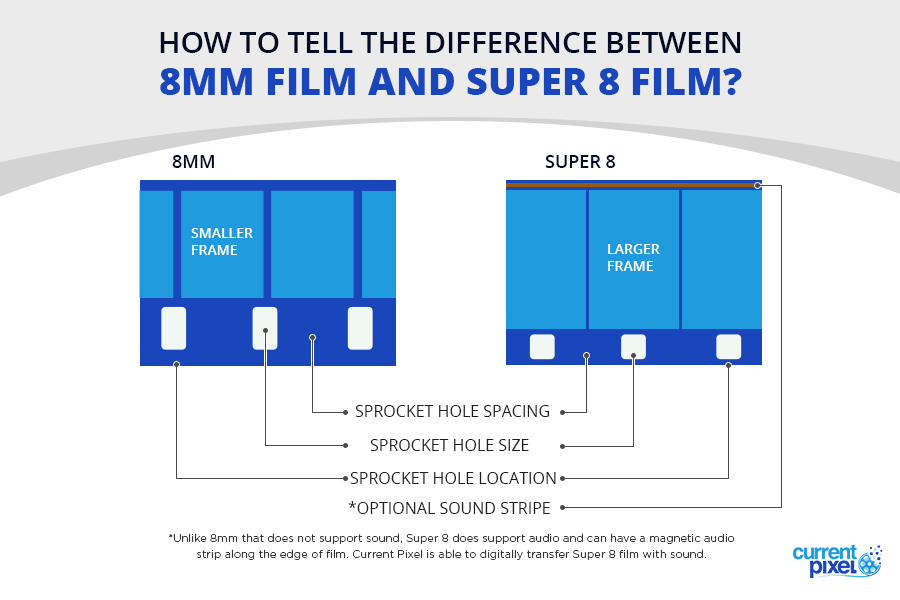

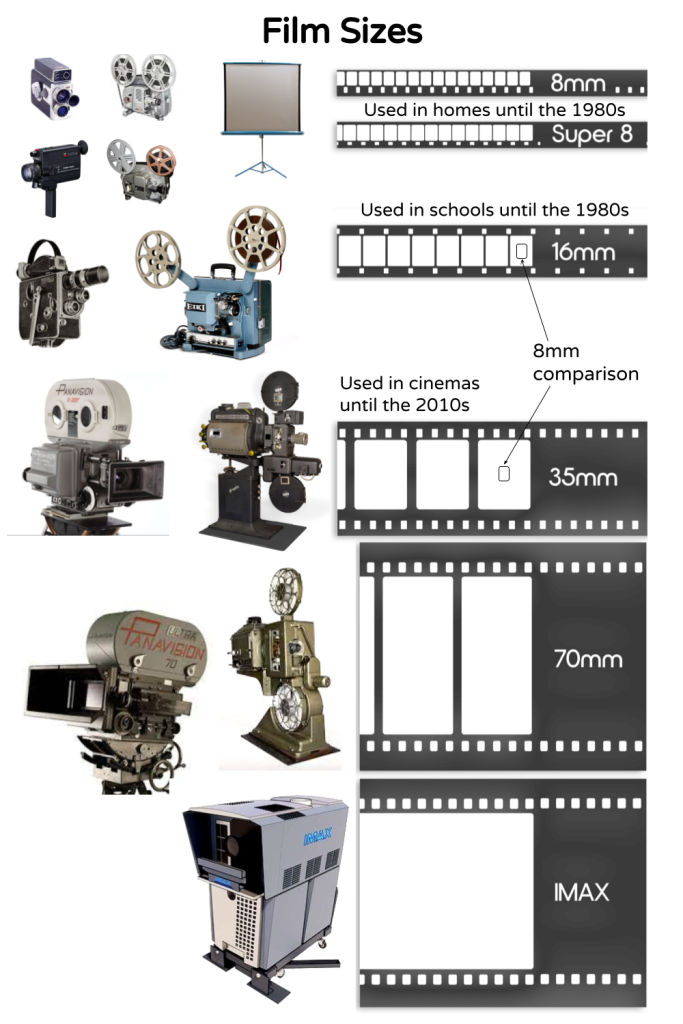

1965 is also when my father’s 1961 camera and 1963 projector were rendered obsolete, since that is when higher-quality Super 8 film became available. Its exposed area was larger and that film was loaded into the camera in cartridges, rather than having to thread it into the camera.

My father, however, never upgraded. He continued to shoot standard 8 mm film until abandoning shooting movies entirely in 1979, five years after Kodak introduced Ektasound: magnetic sound recording on Super 8 film. We would occasionally watch the old silent home movies, and he had paid another $40 in 1976 to have the projector serviced.

The last use of his Kodak camera was when I shot a few films with friends in junior high circa 1980. Decades ago, the chain drive in the projector came loose, but I was able to repair that myself. This time, the repair was simply replacing the light bulb.

The Bulb

I switched to using LED bulbs around the house over a decade ago, so replacing burned-out light bulbs is now pretty rare around Meador Manor. I winced when the one in the projector went out, recalling from childhood that it was a weird-looking thing, and replacing the bulb in a 60-year-old projector was bound to be expensive.

The projector owner’s manual (yes, my father saved everything) indicated that I needed a Philips 13113C/04 lamp, which was an optically advanced bulb with a rear ellipsoidal reflector and hemispherical front mirror to produce a narrow beam with little light loss. It has a little chimney on top so that it won’t blacken over time; the evaporated tungsten rises upward with the heat and is deposited up there.

I was surprised to find that Walmart.com had them for sale, but they listed for $132 each. Amazon had some of the bulbs for about $100, which was still too pricey for me. I was eventually able to find an eBay listing for $65, which would do.

But it took awhile for the bulb to arrive, and in the meantime, I reconsidered my approach.

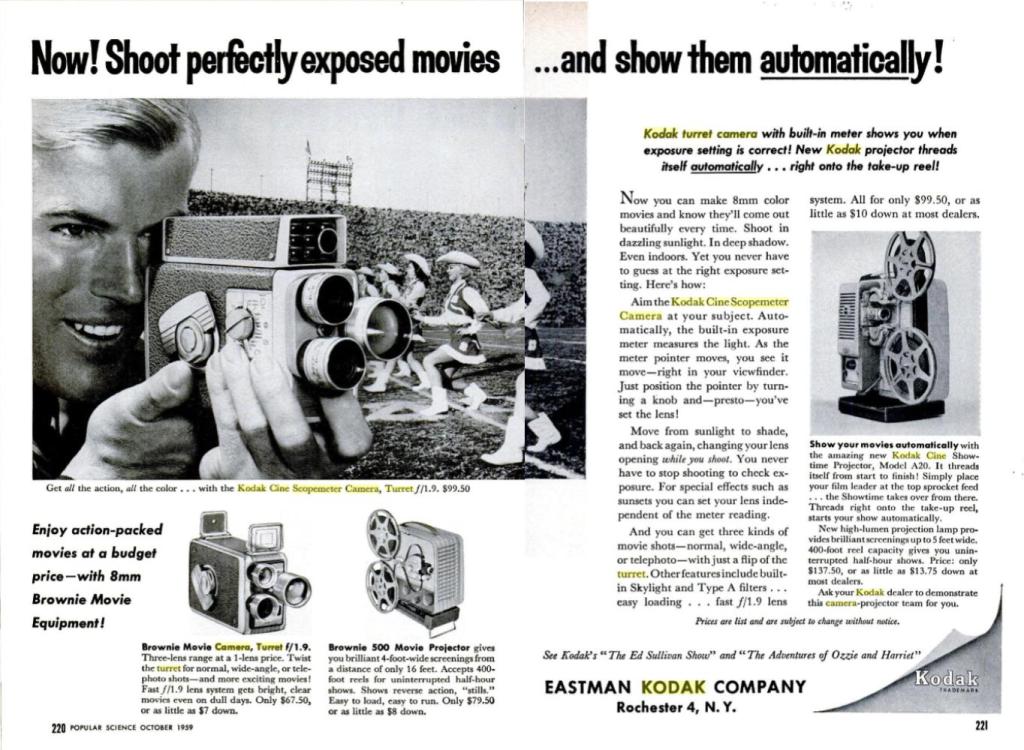

The Camera

Dad purchased his camera in December 1961, a few months after my parents were married. It was a Kodak Cine Scopemeter Turret f/1.9 which Kodak produced from 1958 to 1962. It had 6.5 mm wide-angle, 13 mm normal, and 24 mm telephoto lenses on a rotating turret, and you could shoot with no filter or use Daylight or Skylight filters for different conditions.

Dad’s model retailed for $100 in 1959, which would be about $1,000 in 2024 dollars. Fancier units had electric eyes to adjust the exposure, but with Dad’s you had to set an exposure index on the viewfinder box for the type of film being used and then adjust the lens opening to try and center an exposure pointer in the viewfinder.

Dad also had a four-lamp photoflood bar which had to be used when shooting indoors because the color film was so insensitive to light. It was blindingly bright if he switched on all four bulbs, and they would get very hot.

He also had mounted on a board his editing equipment, consisting of a little illuminated viewer, two hand-cranked spindles, and a splicer. Each roll of film was 25 feet. He threaded it into the camera, exposed one half of it, and then flipped the film over and ran it back through the camera to expose the other half. The film lab would slice the film down the center and process it into a 50-foot reel of film, which would yield about 2 or 3 minutes of footage.

Dad would splice the three-inch reels together to form seven-inch reels with 26 to 29 minutes of footage. He would scribble on a piece of scrap paper what the different scenes were, and stuck those in the can with each reel.

Digitizing old movie film

I’ve digitized a LOT of old film lately. I previously shared how I invested a thousand dollars in a couple of print and film scanners, and I’ve now scanned over 20,000 photographs at work, and have started scanning my parents’ still photographs. At work, I’m currently working my way through over 50 cans of black-and-white 35mm photographic film negatives, cutting it down to 6-frame strips that I manually run through a scanner, but that approach would never work for movie film shot at 16 or more frames per second.

The size of the exposed area of an 8mm film is quite small: less than 5 by 4 millimeters. The films I watched in elementary school and junior high in the 1970s were 16mm with over four times that resolution, and the 35mm film commonly used in cinemas before 2010 had over twenty times that resolution.

So for digitizing a movie, the cheap approach is to project it the old-fashioned way and record that with a modern camera. But I knew the limitations of the projected images from the 1960s technology I had inherited, so I decided to make yet another investment. I purchased a film scanner that would digitize the old footage frame-by-frame and output a digital video file.

The Wolverine

There is no clean way to say how many pixels you can resolve on a piece of film, but a rule of thumb is that you can scan 8mm film at 1K (1024×768), 16mm film at 2K (2048×1536), and 35mm film at 4K (4096×3072). So I invested $400 in a Wolverine MovieMaker-PRO that can scan standard and Super 8 movies at a resolution of 1440×1080.

The market for such devices is limited, so they are updated infrequently. The device couldn’t handle SD memory cards with a capacity over 32 gigabytes. All of my SD cards were 128 GB, and Wendy’s was 256 GB. So I ordered a 32 GB card from Amazon for $10 before I thought to search my car.

Back when I was still taking photos with superzoom 35mm digital cameras, I kept an extra SD card in the car. Sure enough, I found an old 16 GB card in the car, slotted that into the scanner, threaded up a three-inch reel of film, and gave it a whirl.

The frame-by-frame scanning process is quite slow. It took over 30 minutes to scan a three-inch reel, and it can take about four hours to scan one of my father’s seven-inch reels. Below is a look at the digitizer in a YouTube review.

The Wolverine outputs MP4 videos that play back at 20 frames per second. My father’s projector runs at 18 frames per second, while the actual frame rate of his spring-wound Kodak Cine Scopemeter Camera from 1961 was supposed to be 16 frames per second.

So after copying a video off the SD card onto my Windows 10 computer, I use CyberLink PowerDirector 365 to slow down the output videos by 20%. I also crop the video image as needed and have the software perform noise reduction and video stabilization.

I was able to compare what the Wolverine produced with what I had shot the cheap way back in 2009 by capturing the output of the original projector. Here is the 2009 transfer:

Here is the edit of the 2024 scan:

The dramatic improvement in the clarity, steadiness, and color of the digitized films led me to abandon using the 1963 Bolex projector for anything except rewinding. Getting the scanned film back onto the original seven-inch film reels using the Wolverine unit would be painfully slow, while the Bolex makes short work of that. I did replace the bulb in the projector, but I never switched it on, just rewinding the films with the bulb off.

In a month I scanned and edited two three-inch reels and six seven-inch reels of film, with only two seven-inch reels and a three-inch reel remaining. So it won’t be long before everything is in my digital archive, and I can return the old film and the equipment to storage.

Some clips I have already shared online are of specialty interest. I posted eight minutes of planes landing or taking off at Love Field in Dallas in 1965:

I also shared glimpses of downtown Atlanta and Stone Mountain in 1969:

I’ve given up my copyright on those two sets of visuals so they are in the worldwide public domain, although the royalty-free music I licensed for the videos is still copyrighted. Much of the material I have digitized is only of personal interest, although the gentle readers of this blog will see a few digitized clips pop up in future posts.

I so enjoy your blog visits. Thank you!