How often do you still use cash? Do you still write some checks? Did you notice credit cards are no longer issued with raised numbers for imprinters? Do you even know what an imprinter is? Do you or should you tap to pay? How we pay for things continues to evolve, and the pandemic accelerated several trends.

The Decline of Personal Checks

It made news when Target stopped accepting personal checks in July 2024, but Aldi, Whole Foods, Old Navy, and Gap had stopped accepting them a decade earlier. While checks have been around for centuries, they are slow, cumbersome, and prone to fraud compared to other payment methods. The average American was writing over sixty checks a year in 2000, but by 2024 that had fallen to less than ten.

Back in the day, schoolchildren would go on field trips to a bank and learn how to write and use a check.

In my case, we rode a school bus to Fidelity Bank’s new tower in downtown Oklahoma City, completed a couple of years earlier in 1972 as part of urban renewal. I remember sitting in a large white room with high ceilings and tall windows as they went over banking procedures, including showing us how to write a check. My mother worked for years at a savings and loan, so I already knew all about that stuff.

My father worked for Cities Service Gas in the First National Bank’s skyscraper a few blocks away. One of my favorite things when visiting his building in the 1970s was to ride the escalator up into its tremendous marble banking hall. The hall is still there, but now refurbished into a restaurant and event space.

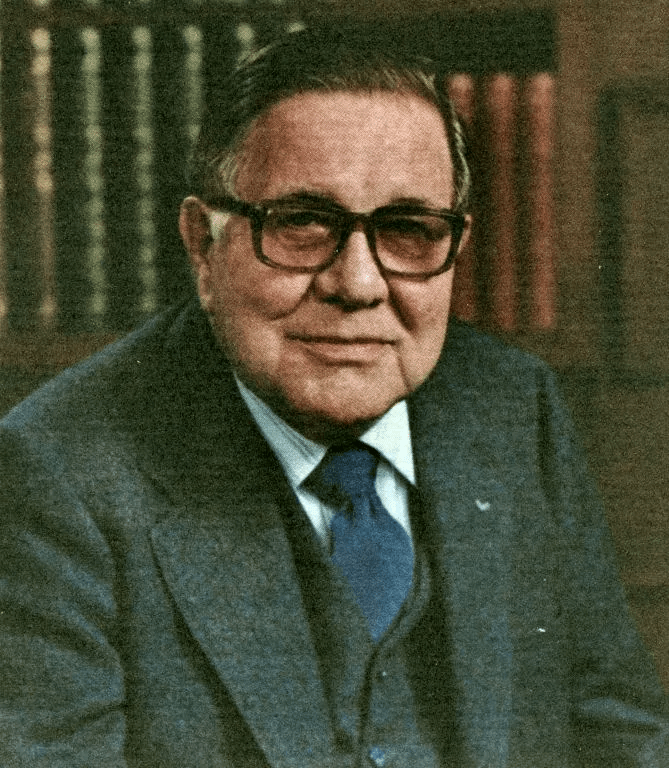

At the time, Fidelity was run by Jack Conn, who spearheaded the Conncourse system of underground tunnels connecting buildings across downtown OKC. It is now known as the Underground with a mile of tunnels that cover more than 20 square blocks.

George Kaiser’s Bank of Oklahoma merged with Fidelity bank in the 1980s oil bust, and I see that Arvest bank took over the former Fidelity/BOK tower in downtown OKC back in 2019. I’ve banked with Arvest, which is owned by the Walton family of Wal-Mart fame, for thirty years.

When I came to Bartlesville in 1989, I opened checking and savings accounts with WestStar, the major local bank at the time, which had begun in 1900 as Frank Phillips’ First National Bank of Bartlesville. In 1994, the Waltons bought out WestStar for $470 million. While I still have around 20 transactions in my checking account each month, I only write one or two checks annually. I’ve heard that fewer and fewer people even know how to properly write a check.

What Took Their Place?

Years ago I started eliminating having to write and mail in personal checks for household utilities. I signed up to have those charges deducted automatically from my checking account. I later started having home and automobile insurance deducted from my checking account as well, although I still write the occasional check for a specialized service like tree removal or fence installation.

The Federal Reserve has released its 2024 Findings from the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, giving us some insights into the shifts in payment methods. Below are the shares of payment instrument use for all payments each year from 2016 to 2023.

Over those eight years, the share of payments handled via personal check dropped by more than half and cash transactions almost halved. Debit transactions increased by 11%, and credit card payments increased by 78%. ACH refers to electronic money transfers between banks and credit unions across the Automated Clearing House network, and those are up 30%. I generate an ACH each month since the school district direct deposits my pay into my Arvest checking account, and I transfer some of that to another bank for my long-term savings since their interest rates are higher.

Cash

For three consecutive years, consumers have reported making an average of seven cash payments per month, so it appears to have a “floor” level. When consumers are asked which payment method they prefer for in-person payments, there has been a significant shift from cash to credit.

That, along with a continuing shift from in-person purchases to online and remote ones, is helping keep the number of cash transactions steady even as the total number of transactions increases post-pandemic.

I should add that the type of payments one makes is correlated to household income. As income increases, the share of transactions done with cash declines in favor of credit cards.

People like me, who are 55 and older, use cash more than younger generations.

But all age groups are making the switch from cash to credit.

Person-to-person payments have shifted greatly from cash to payment apps.

I’ve experienced that myself, with Wendy routinely sending me money via Venmo when she charges something via an app on her iPad.

Credit Cards

Back in 1970, when I was a kid, only 16% of U.S. families had a bank-type credit card. However, 45% had a retail store card. I recall that my mother had specific credit cards for Sears and J.C. Penney. The latter seemed ironic since she remembered how Penney’s was a cash-and-carry operation until 1958, originally promoting their lack of store credit as a way for consumers to avoid building up debt.

Mom kept using the same cards for decades. They had no expiration date and no magnetic strip, just embossed numbers and her name.

Eventually when she would hand her card over, the clerk would pause, comment on how old the card was, and would have to reach under the counter to pull out an old manual imprinter since the card couldn’t be scanned by the register. They would place the carbonized sales slip and the card in the device and either pull down a lever or slide a bar back and forth to create an impression of the embossed card data.

Finally, sometime in the 21st century, the stores forced Mom to give up her old cards, replacing them with modern ones with magnetic strips.

By the late 1990s, two-thirds of families had bank-type credit cards. The retail cards where the store, instead of a bank, issued the credit began to wane.

Credit card use plateaued at about 75% for the first years of the 21st century, but then rose to over 4 out of 5 families in the late 2010s.

These days imprinters are utterly obsolete, and our latest credit and debit cards lack embossing. They still have have the magnetic strip on the back for old-style swiping. Encoded on the strip are the credit card number, your name, the expiration date, etc.

But in 2015 EMV chips began to be added to the credit cards in the USA, over a decade after they were introduced in Europe and five years after they came to Canada. EMV stands for Europay, Mastercard, and Visa, and using the chip is more secure than the magnetic strip, since it generates a transaction-specific, one-time code that cannot be duplicated ahead of time instead of sharing the actual credit card number.

Most credit cards are still “dip and sign” ones in which you insert the card in the reader, wait for the signal, and then may be prompted to provide your signature, although most card issuers no longer require a signature since signatures are not effective at preventing fraud.

However, some stores still require a signature for transactions over a given amount, have old card terminals that rely on the magnetic strip instead of the chip, and restaurants that lack pay-at-the-table terminals often, but not always, require a signature to validate a tip the customer adds to the merchant slip.

Some expect us to migrate to cards where using the chip in a terminal also requires that you enter a Personal Identification Number, as one commonly must do with bank debit cards. But a newer technology offering better security is preferred: tap-to-pay. A card (or smart phone) with tap-to-pay capability has an embedded antenna.

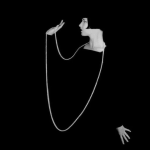

A CT or computed tomography scan of a contactless pay credit card reveals the antenna wires around its perimeter which then coil tightly around the EMV chip.

When you use tap-to-pay, the pay terminal uses alternating current to generate an electromagnetic field at a frequency of 13.56 million cycles per second. That field oscillates across the wires in the credit card, inducing an electrical current in it to power a tiny integrated circuit in the card. The card rapidly changes its resonance to create detectable fluctuations in the terminal’s electromagnetic field, thus communicating with the terminal.

Like transactions where you insert the card to read the chip, each contactless card payment creates a one-time code and avoids transmitting the actual credit card number. But contactless tap-to-pay is even better since you never have to insert your card in a terminal. That avoids falling victim to a terminal secretly outfitted by criminals with a skimmer that actually reads the magnetic strip to gain your credit card number and other information.

I love the tap-to-pay feature. I even instructed one bank to issue me a replacement card since the new one would have tap-to-pay and that was lacking on the card they had issued me a few years ago. But does the use of radio waves for tap-to-pay mean that crooks could walk by you and scan your credit card?

No. The effective range for tap-to-pay is deliberately designed to be quite short, maybe a few centimeters, and the card doesn’t actually transmit the account number, but instead a one-time code. The risk of electronic pickpocketing is minimal compared to physical card theft. So I don’t bother worrying about wallets that block radio waves.

Plus, in the U.S. there is little if any consumer liability if a fraudulent purchase is made. The real danger inherent to using a credit card is in its name: credit.

As people use credit cards more, the debt associated with them is building even as the personal saving rate, which spiked during the pandemic, has fallen. Bear in mind that the debt is volumetric while the saving rate is a flow, but the contrast in the trends is still interesting.

As the Federal Reserve raised interest rates from March 2022 to July 2023 in order to combat high inflation, that prompted credit card interest rates to spike. Axios reported that in September 2024 the average credit card interest rate was at 20.78%, close to the highest on record, and the current average interest rate on store-branded retail cards is a whopping 30.45%.

So if you’re not paying off your credit card bill each month, it might behoove you to start using debit cards instead. Merchants prefer them anyway since their processing fees are lower, disputes and chargebacks are easier to handle, and the money is available to the merchant more quickly.

How we pay will continue to evolve. Here’s hoping we can continue to reduce the friction as well as the fraud.