Over 2,000 years ago, someone sculpted a full-length lifesize bronze statue of a man on the Greek island of Delos. Such works cost about 3,000 drachmas — the equivalent of two years’ salary for a rich citizen.

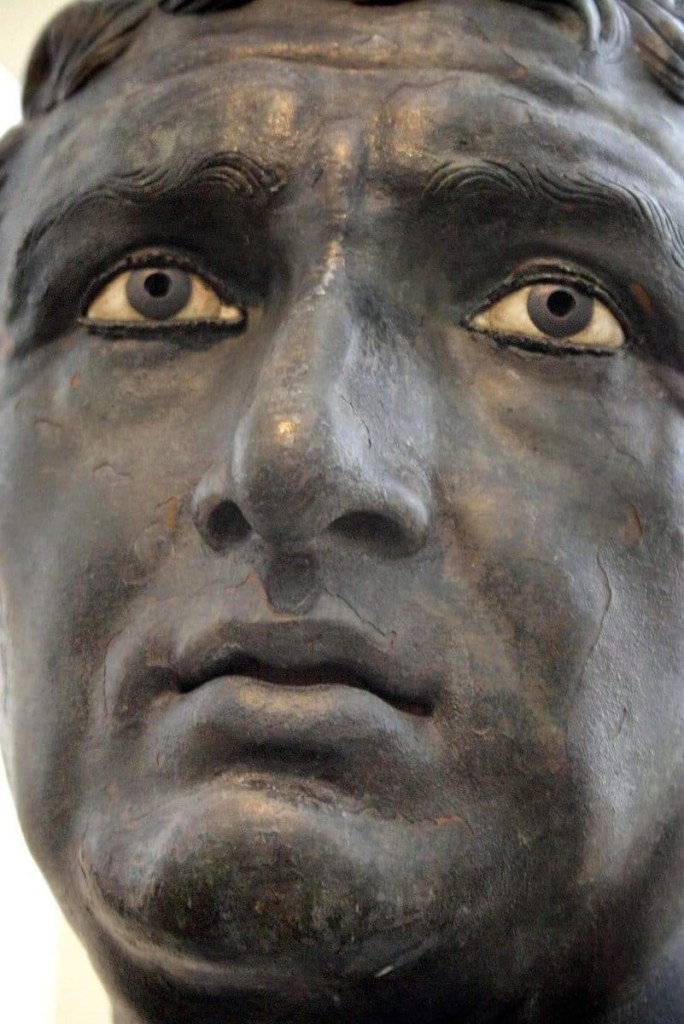

Only about 200 of tens of thousands of such bronze sculptures crafted by Hellenistic artisans survive. Centuries of tarnish have given them dark mottled finishes, but when first minted they would have approximated the color of a tan Greek, with eyes of glass and colored stone, fringed with delicate bronze eyelashes.

Most of the sculptures have lost their lifelike eyes in their struggle against time, buried in sand or sea or ash. Yet this gaze endured.

In 1912 this head was unearthed at the Granite Palaistra, a training ground for athletes. It likely belonged to an honorific statue of a citizen, and antiquities experts say his expression was likely meant to portray civic devotion.

“The face is showing what he’s being honored for — the zeal, attention, care, and energy he’s expended on behalf of his fellow citizens,” shared Jens M. Daehner, a curator at the Getty Museum.

Nevertheless, we know him as the worried man of Delos.

Delos is a tiny island, only a bit over one square mile in area, that was a cult center for the gods Dionysus and Leto. A Greek saying was “ᾌδεις ὥσπερ εἰς Δῆλον πλέων” meaning “you sing as if sailing into Delos” when someone was in a happy and light-hearted state.

But it is never that simple, is it?

When this statue was sculpted in the 100s BCE, the Romans had converted Delos into a free port, and it had become the center of the slave trade. Roman traders went there to purchase tens of thousands of slaves captured by Cilician pirates or abducted in the wars following the destruction of the Seleucid Empire.

It wasn’t long before trade routes changed, and Delos entered a sharp decline before the end of the first century BCE. It was attacked and looted by Mithridates, the King of Pontus, in 88 BCE and again by pirates in 69 BCE. By the second century of the Common Era, the traveler and geographer Pausanias noted that Delos was uninhabited save for a few sanctuary custodians, and six centuries later Delos was entirely abandoned.

We cannot know what our worried man was actually thinking or feeling amidst a prosperous time, but his expression mirrors my own at this point in the evolution of the constitutional republic I was fortunate enough to be born into.

He lived in the time of the Roman Republic, which began with the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom centuries earlier. That Republic was in a state of near-perpetual war, and in its last century was torn by civil strife, attributed by the ancients to moral decay from wealth and the hubris of Rome’s domination of the Mediterranean.

Modern sources cite its destruction to wealth inequality and a growing willingness by aristocrats to transgress political norms. Sound familiar?

Of course the Roman Republic later fell, to be replaced by an authoritarian Empire. That brought 200 years of relative order, economic prosperity, and stability, at the price of near-absolute rule by a series of emperors.

The last of Rome’s “Five Good Emperors”, Marcus Aurelius, wrote in his personal journal: “Never let the future disturb you. You will meet it, if you have to, with the same weapons of reason which today arm you against the present.”

I am armed by reason, comforted by experience, and counseled by patience. Yet my gaze is pensive.