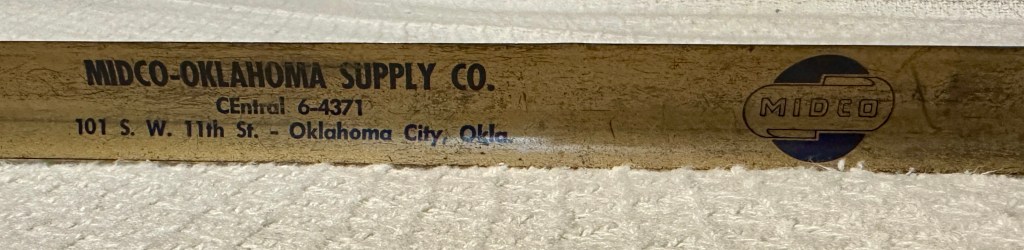

One of my favorite tools is from the early 1960s: a metal roll-up yardstick that I inherited from my parents. I will delve into its design in a later post, but my preternatural curiosity has me chasing after a different rabbit.

Companies used to distribute yardsticks as free advertising. They would print their name, logo, address, and phone on them hoping that you might see it repeatedly over the years as you made use of the tool. In this case, MIDCO-Oklahoma Supply Company of Oklahoma City was the advertiser.

You can tell the yardstick is from the early 1960s since the phone number for MIDCO is in the old exchange-name 2L5N format. I couldn’t help wondering what MIDCO had been, and if it was still around. Answering that led me back to Hubcap Alley and to contemplate what my hometown gained and lost in reinventing itself.

MIDCO

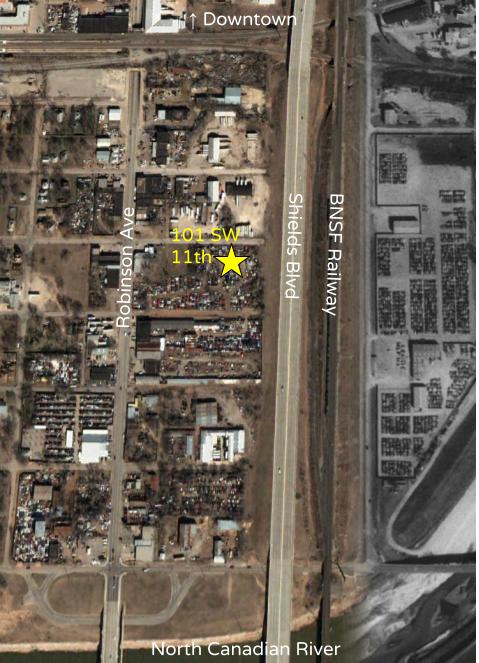

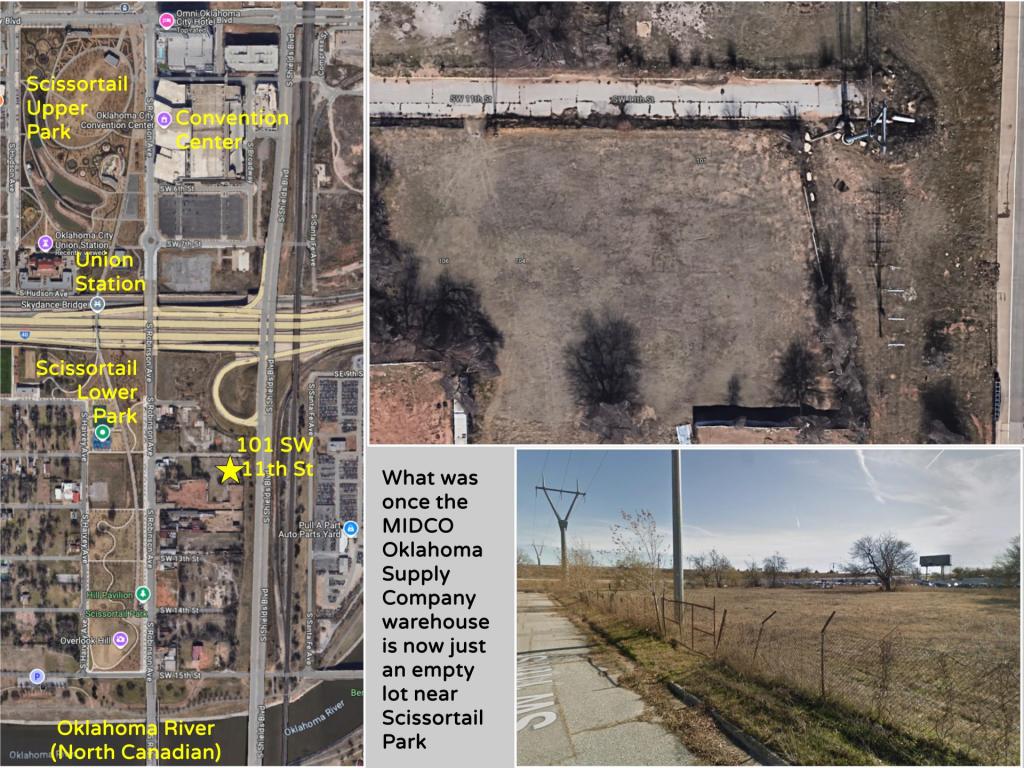

MIDCO was Mid-States Supply Company, which began in 1947 in Kansas City, Missouri. It was a PVF supplier — pipes, valves, and fittings. When it opened a warehouse in Oklahoma City in 1963, it needed a cheap industrial area where its inherently ugly all-business aesthetic would fit right in. So it had a couple of obvious choices: the railroad warehouse area of Bricktown or the automobile scrapyards along Hubcap Alley.

Bricktown

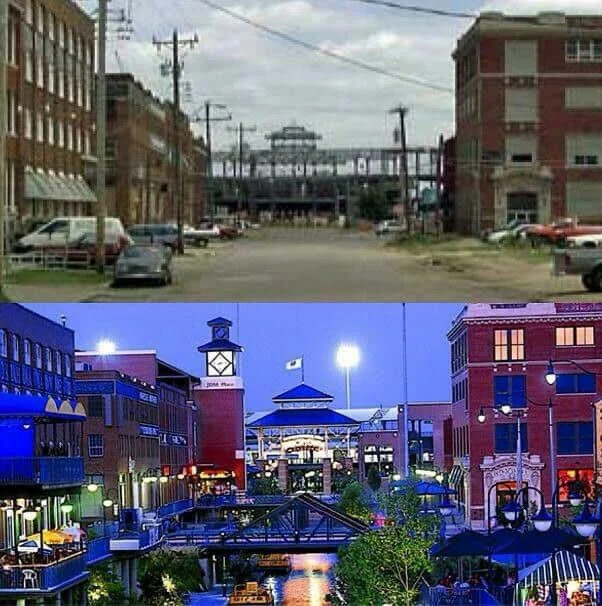

In the late 19th and early 20th century, four railroad companies had freight operations east of the tracks that ran along the eastern edge of the central business district. To avoid fires, they constructed brick warehouses from 1898 to 1930, along with working-class houses nearby. Bricktown declined in the Great Depression, and after World War II many residents left for the suburbs along subsidized highways. Railroads restructured with a lot of freight traffic shifted to highway trucks. By 1980, Bricktown was a cluster of abandoned buildings. So Bricktown was in steep decline in 1963, and MIDCO didn’t locate there.

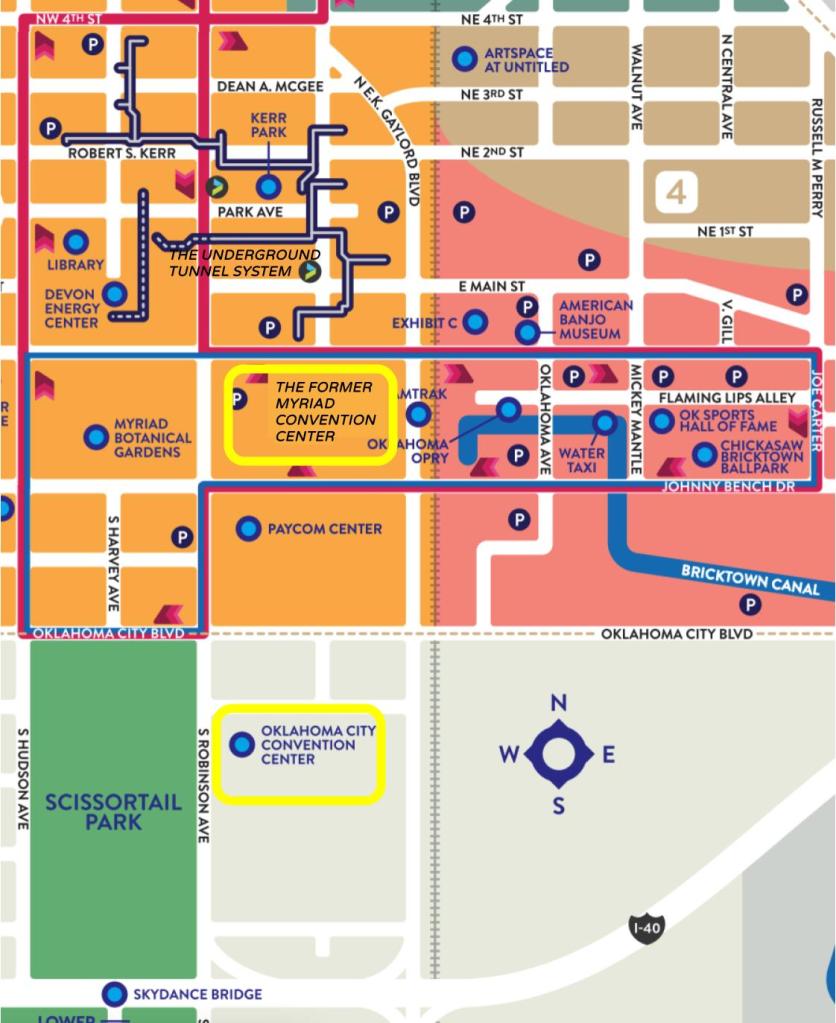

In the 1990s, OKC residents were persuaded to invest in themselves by approving a sales tax for MAPS which renovated the Civic Center Music Hall, renovated and expanded the Myriad convention center, constructed a ballpark and sports arena, and dug the Bricktown Canal to transform that area from an abandoned warehouse district into a more lively entertainment one.

The success of the first MAPS led to three later MAPS projects. MAPS 3 would destroy Hubcap Alley.

Hubcap Alley

Almost as soon as automobiles became a part of city life, working-class families set up repair, tire, and accessory shops. There are blocks of downtown Bartlesville, where I now live, that were dotted with tire and battery companies, metal shops, and garages. Several buggy and harness firms transformed themselves to service the horseless carriages.

In Oklahoma City, the stretch of Robinson Avenue south of downtown toward the dirty ditch officially labeled as the North Canadian River became Hubcap Alley, not to be confused with Automobile Alley up north on Broadway where the car dealerships were located.

Working-class families set up over two dozen repair, tire, and accessory shops along Hubcap Alley, along with big auto salvage scrapyards. If you needed a car part and couldn’t afford new, which was true for most of the folks in Oklahoma City, you would head to Hubcap Alley.

It was the birthplace of Hibdon Tires, and it was anything but pretty. So in the 1950s, it became one of the targets of the first wave of Urban Renewal. Hubcap Alley was considered an embarrassment, an ugly gauntlet for out-of-state visitors passing along US 77 on their way to downtown.

However, the businesses successfully fought back against the Urban Renewal in the 1950s, and MIDCO planted itself at 101 SW 11th in the heart of Hubcap Alley. I don’t know how long it lasted, but by 2002 that property had just become part of the auto salvage yards.

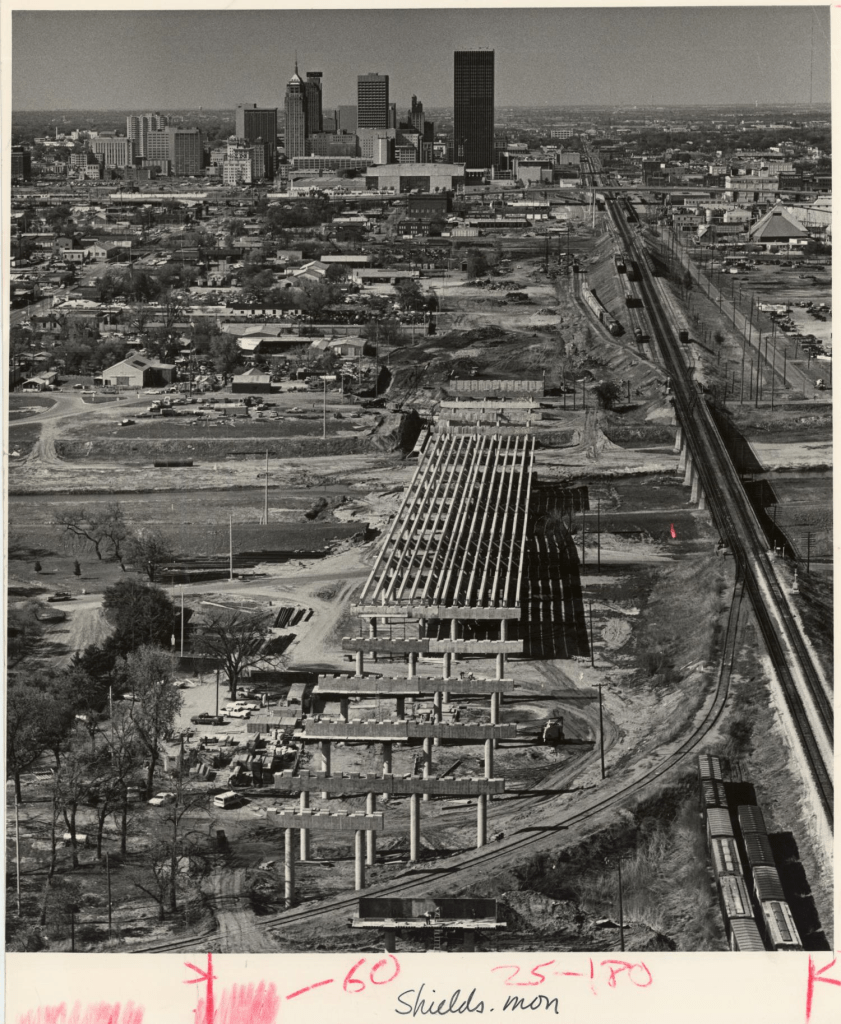

In the 1970s, Urban Renewal became stronger than ever as retail downtown collapsed. But even as it was destroying whole blocks of downtown, Urban Renewal spared Hubcap Alley by extending Shields Boulevard northward to downtown, rerouting US 77 off Robinson Avenue.

The snoots still fretted about how building the Shields extension into downtown as an elevated road, instead of at grade, would ensure no development along that stretch, and thus spare the unsightly warehouses and junkyards to the west along Hubcap Alley as Shields stabbed northward alongside the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railway tracks.

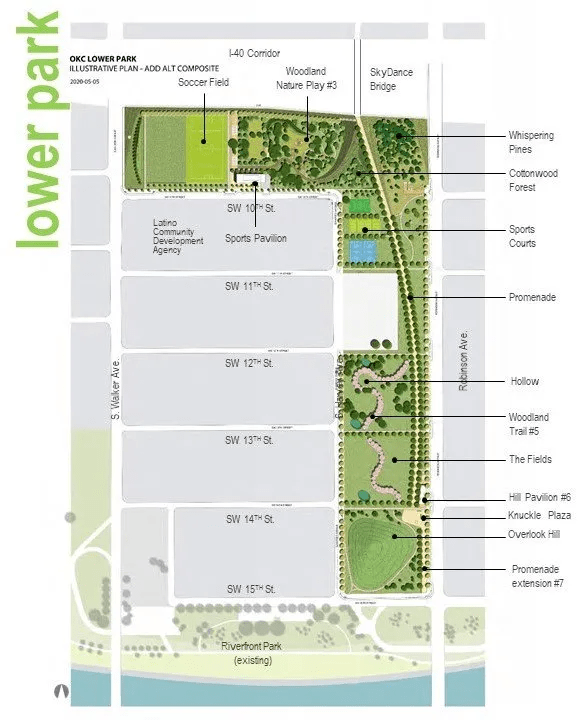

In 2009, the MAPS 3 project approved by city voters included a plan for a massive park connecting Capitol Hill, the Oklahoma River, and downtown.

By the way, lest a non-native form the wrong impression, Capitol Hill was once a small town south of the river, two miles from the actual state capitol. A newspaper man purchased the hill in 1900, hoping it might become home to the state capitol, but the capitol was instead built a mile northeast of downtown. Another scheme for a suburb location for the capitol led to the non-existent Putnam City, a story I’ve shared previously.

As for the Oklahoma River, that is a renaming of a seven-mile stretch of the North Canadian that now has several locks creating small lakes for rowing, kayaking, and canoeing regattas. You guessed it — that was another MAPS 3 project, part of the same package that dealt with Hubcap Alley.

MAPS 3 funded the city’s acquisition of the west side of Robinson Avenue from the then-new rerouting of Interstate 40 all the way south to the river. Car shops and junkyards were transformed into the skinny lower half of Scissortail Park.

As intended, that meant that the remaining scrapyards on the east side of Robinson lost business as former customers presumed all of the junk dealers were gone. It also led hopeful developers and speculators to start buying those properties, betting on rising values near the new park. A&A Auto Parts & Salvage, the last holdout with about 400 cars on its lot, closed in 2022.

So 101 SW 11th Street is now just an empty lot east of the Scissortail Lower Park, south of the new convention center, part of the landscape that MAPS 3 denuded.

The snobs finally won, and the lights went dark along Hubcap Alley. Below you see the fancy northern part of the park just west of the new convention center, with the distinctive spikes of the Skydance pedestrian bridge to the south across Interstate 40.

I’ve yet to see Scissortail Park or the new convention center, but I’ve driven under Skydance Bridge a few times. If I were ever at the convention center, I might walk across Skydance Bridge to the lower park, which is far less compelling than the northern portion since the lower park was really just a mechanism for destroying Hubcap Alley.

A Lost World

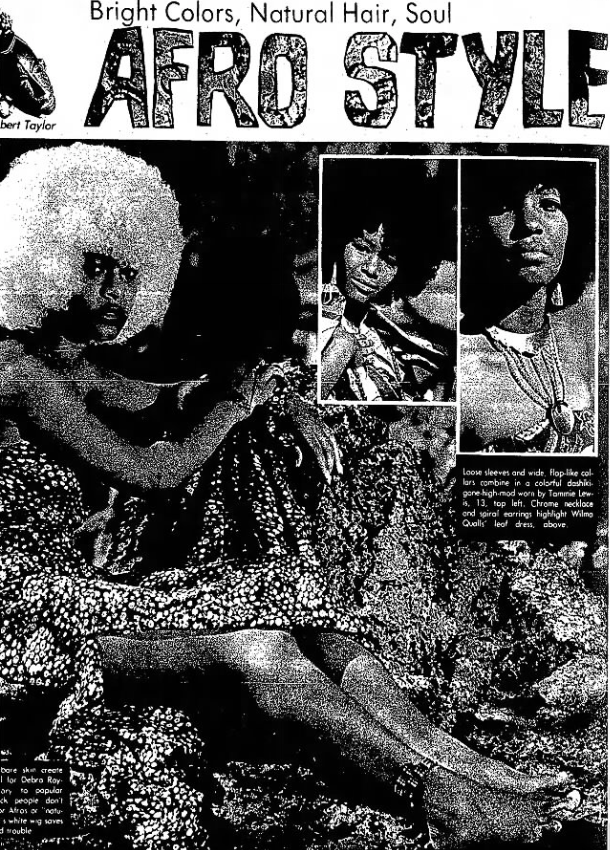

I have rather mixed feelings about it all. I grew up in Oklahoma City and knew it was not a beautiful town, but rather a flat, sprawling, and eminently practical-minded mess. I grew up in a city that sported the junkyards of Hubcap Alley, the world’s largest stockyards, and the diaspora of Deep Deuce after the Civil Rights era, when the black culture that had earlier created Ralph Ellison stretched out into a truly funky stretch of 23rd Street.

The Soul Boutique offered high-end mod and Afro fashions along an urban corridor that looked like the set of Starsky & Hutch, with big colorful Cadillacs sporting curb feelers and people strutting along in crushed velvet.

It was all rather gritty. The collapsing downtown spread urban blight and street crime. The fancy shops on the ground floors of the skyscrapers were closing, and Main Street was emptied while I explored the underground Conncourse.

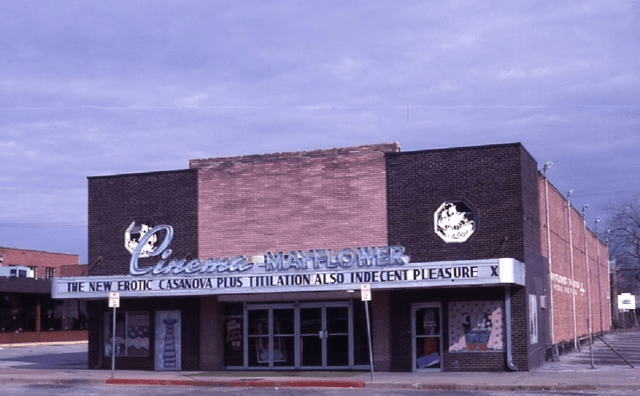

The old Mayflower cinema on 23rd Street had opened in 1938 showing Bing Crosby in Pennies from Heaven. It had a nautical theme contrasting to the southwest look of its architectural twin, The Bison. While the Bison closed in 1971, the Mayflower survived…by becoming a porno house directly across the street from the famous Gold Dome of Citizens State Bank.

OKC knew it was in trouble by 1962, when 53 downtown retailers had closed or moved to the suburbs. City leaders Dean McGee, Stanley Draper, and E.K. Gaylord pushed for Urban Renewal, and businessmen hired architect I.M. Pei to redesign the 528 acres of the central business district.

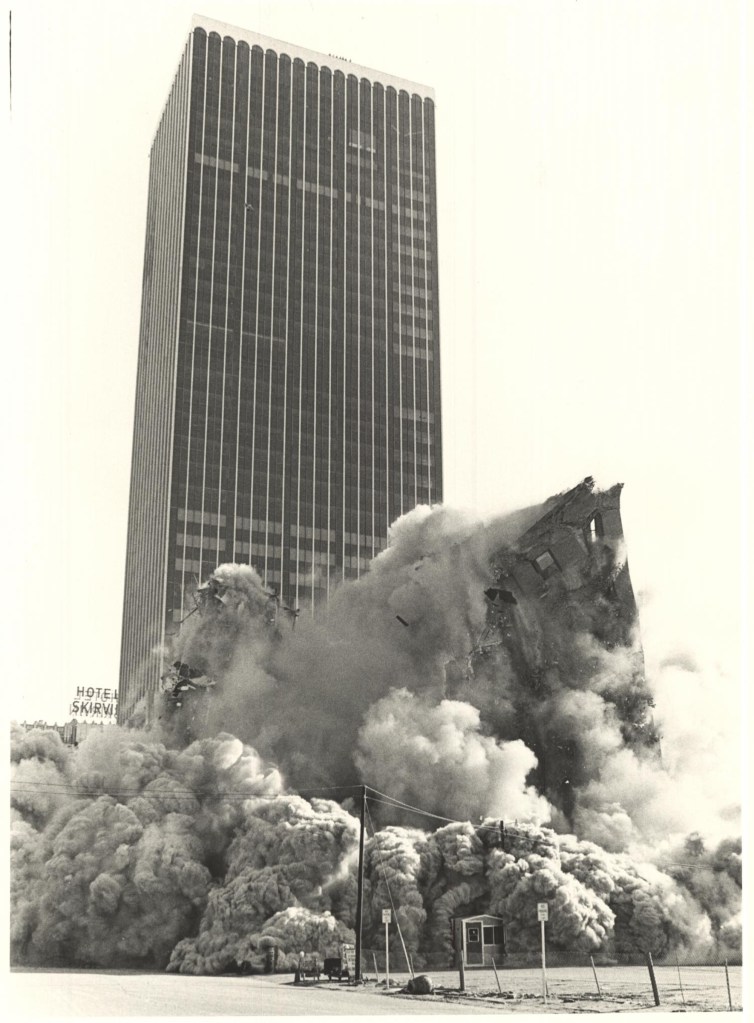

His way of dealing with the small lots and aging structures was to demolish hundreds of buildings to form superblocks for larger-scale development. To his credit, his original plan did call for retaining notable landmarks like the Biltmore and Huckins Hotels, but that wasn’t how things went.

The large-scale demolitions began in 1967, but the plan ended up destroying far more than it rebuilt. In 1971, the Huckins Hotel at Broadway and Main, which had once been the temporary state capitol, was the first of the city’s buildings to be brought down with explosives.

The big John A. Brown department store was to be rebuilt, but in 1974 the out-of-state Dayton Hudson Corporation announced they would entirely abandon downtown for suburban malls. The site for a Main Street Galleria was cleared, but it just became a surface-level parking garage.

Along with Brown’s, the beautiful old Criterion Theater and the Baum Building had been torn down, but the Galleria shopping area never materialized, and the Century Center Mall ignored the street and never thrived.

My parents would sometimes take me downtown to visit my father’s office in the First National Building downtown. Eventually we parked at the new Century Center, and I was struck by the oddity of driving up and down its spiral ramps. It was strange to see so much of the city razed to make way for megastructures.

Just across the street was the brutalist and cheaply built Myriad convention center. My high school proms and commencement were held there, and I was struck by its unadorned and grim bare concrete interiors.

In 1977, one of the last acts of destruction was blowing up the old 26-story Biltmore Hotel. The original Pei Plan called for “Tivoli Gardens” around the hotel, but the hotel was judged to no longer be economically viable. The Myriad Botanical Gardens simply grew a bit to swallow up the Biltmore plot.

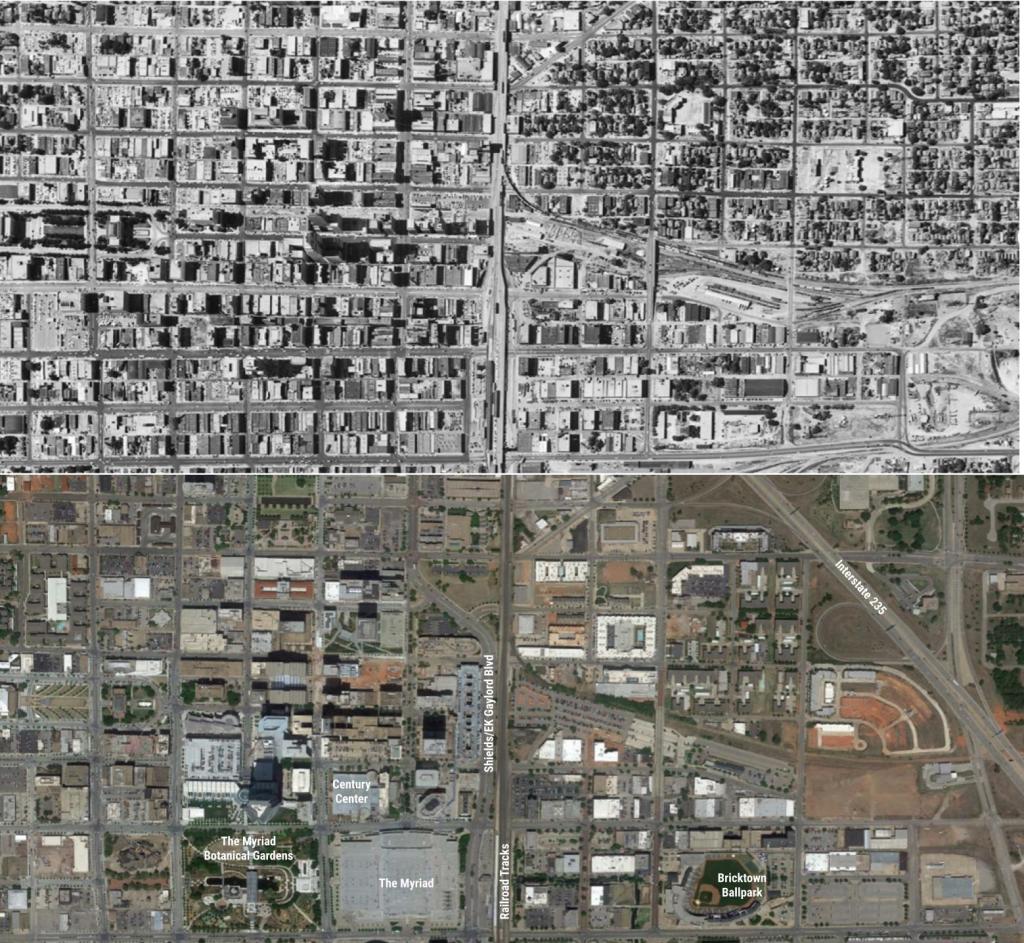

The Oklahoma City Urban Renewal Authority’s contractors leveled 447 buildings, and private owners tore out another 75 between 6th and I-40, from Shartel to the Santa Fe.

The street grid and fine-grained commercial core of the early 20th century was replaced with superblocks, large public projects, parking facilities, and freeways.

The city reeled for some time after the appalling destruction of the 1970s Urban Renewal, which had been followed by the 1980s oil bust. We should bear in mind that many of the old buildings failed to meet modern safety and accessibility codes, had antiquated heating, and could be difficult to retrofit for air conditioning. The Biltmore, for example, unlike the old Skirvin, First National, and Colcord buildings, lacked the high ceilings needed for ductwork retrofits, so it used window air units.

The Colcord Building of 1909 was the city’s first skyscraper with 14 floors stacking up to 145 feet. Charles Colcord built the office tower of steel-reinforced concrete, having seen the devastation in San Francisco from its 1906 earthquake and fires. But saving it cost $2 million in the 1970s; there simply weren’t the resources to make similar investments on a large scale. It is now a luxury hotel, and Wendy and I enjoyed a stay there. Time marches on, and now the Colcord is dwarfed by the neighboring Devon Energy Center, a ridiculous 844-foot 50-story example of corporate hubris.

Oklahoma City finally tried again at a modified form of urban renewal in the 1990s with MAPS, which at least combined some big new structures with renovations and repurposing of some of the remaining old ones. Bricktown was revived by its ballpark and big ditch.

MAPS 3 addressed the Myriad’s shortcomings by building a new convention center to the south, which struck me as counterintuitive, placing it at some distance from several major hotels and doubling the walk to Bricktown’s restaurants. Oklahoma City’s summer weather is anything but pedestrian-friendly, and I’m skeptical about the expensive new streetcar system making up for the inconvenience. The old Conncourse tunnels, now called The Underground, are now blocks away, and were never extended to Bricktown anyway.

Just as the Myriad had its gardens to the west, MAPS 3 ensured that the new convention center would have the even larger Scissortail Park. It all seems rather wasteful and duplicative, and a year ago OKC voters doubled down on that approach by approving a sales tax extension that will fund a new arena on the site of the old Myriad. That will render obsolete the intervening downtown arena built by the first MAPS project, an $89 million investment from 1999 to 2002. That first MAPS arena only had a useful life of a bit over 20 years, and the new arena will end up costing a whopping billion dollars.

I find it all a bit bewildering and alienating, but I’m not a sports fan and I haven’t lived in OKC since 1989. So I don’t pretend I know better than the people who live and play there. What I do know is that the decades of MAPS projects have allowed my hometown to sand and scrape off much of the grit that I grew up with. The city is far sleeker and more appealing these days, yet it is still busily gnawing holes in its inner core in a continuing quest for bigger and better.

What does it all mean? That what I think of as my hometown is long gone, and if I’m honest, maybe that’s for the best.