Mary Stewart was a British novelist, born Mary Florence Elinor Rainbow in 1916. She taught in grade schools and lectured part-time at Durham University before moving to Scotland with her husband in 1956. After nearly dying from an ectopic pregnancy and left unable to bear children, she wrote her first novel and effectively launched the genre of romantic suspense, producing a score of novels that sold over five million copies.

A very private person, she reacted against the “silly heroine” of mid-20th-century thrillers who “is told not to open the door to anybody and immediately opens it to the first person who comes along”. She reportedly crafted poised, smart, highly educated young female characters who drove fast and knew how to fight but were also tender-hearted with a strong moral sense.

A change of direction came in the 1970s when she surprised her publishers with a novel about the early years of Merlin, The Crystal Cave, which led to four more Arthurian books. I presume she was influenced by T.H. White’s success with The Once and Future King as well as her own fascination with Roman-British history.

Arthurian Attempts

I read The Crystal Cave back in 2020, a few months before Covid-19 changed our world. I’d waited decades to try another book based on Arthurian legends.

As a child, I’d enjoyed The Hidden Treasure of Glaston by Eleanore M. Jewett, which was published in 1946 and was a Newbery Honor book about a medieval boy’s search for the Holy Grail in an area associated with the mythical King Arthur. In junior high or high school, I recall reading a modern English translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in one of my English classes.

In 1983, when I was in high school, Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon was published. I noticed its striking cover at the Henry Higgins bookstore in our local shopping center and eventually read it. That retelling of Arthurian legends from the perspective of the female characters was quite popular in its day, long before disturbing allegations about the author’s behavior came to light.

However, I did not enjoy The Mists of Avalon, despite the praise heaped upon it. I don’t recall if I finished it or not, but I remember finding it obscure. I also didn’t care for most movies or miniseries set in King Arthur’s time, save for the hilarious Monty Python and the Holy Grail. So I generally avoided Arthurian books, although I did listen to the engaging J. Rufus Fears lecture on Arthurian myths.

In early 2020, for reasons I do not recall, I decided to read something Arthurian. I had no intention of trying 1485’s Le Morte d’Arthur, and I wasn’t ready to commit to T.H. White’s fantasy retelling. I chose Mary Stewart’s The Crystal Cave because it was praised as being more realistic and historical and is told from Merlin’s viewpoint.

It was yet another bildungsroman, following Merlin from age six to young manhood. Thankfully it was indeed light on the fantasy. Instead of a young adult sword and sorcery tale, it was a more serious evocation of fifth century Britain. I recall it as well-written, but I was repelled by Merlin’s machinations to allow Uther Pendragon to tryst with Ygraine and thus create Arthur, and I didn’t continue with the later books in the trilogy. I generally dislike tales of feudalism outside of listening to the Kingsbridge series by Ken Follett or the Chronicles of Brother Cadfael by Edith Pargeter, who wrote them as Ellis Peters.

The onslaught of Covid-19 disrupted my world for some time, and I forgot about Mary Stewart, remaining oblivious that she had pioneered romance suspense with capable female protagonists.

A Forgotten Disneyfication

Then, over five years later, whilst wasting my time on YouTube, the algorithm offered up The Moon-Spinners never had a chance by Once Upon a Record. For whatever reason, I clicked on the video about a 1964 Disney film that was completely overshadowed by Mary Poppins.

As a Gen-Xer, I wasn’t around in 1964, but I’ve seen that year’s Mary Poppins many times, while I had never heard of The Moon-Spinners, and I’ve never seen Hayley Mills other than in some episodes of The Love Boat back when I was a bored teenager in a home with only broadcast television. Hayley’s 1964 film was edited into a three-part movie of the week and shown on The Wonderful World of Disney in 1966, but it was never reissued in theaters.

I had no interest in watching the Disney film, although I was intrigued by the beautiful shots of real-world locations in Crete. Ever since reading Mary Renault’s The King Must Die and The Bull from the Sea for an undergraduate college seminar on ancient Greece, I’ve been interested in Minoan Crete and Sir Arthur Evans‘ fantastical recreations.

The Once Upon a Record video mentioned that Mary Stewart had authored the 1962 book the movie was loosely based upon and how she was not pleased with Disney’s adaptation — a common authorial complaint for Disneyfications. I’ll blame the intervening Covid chaos for the mention of Mary Stewart in the video failing to remind me of reading The Crystal Cave a half-decade earlier.

Ever curious, I downloaded a sample of The Moon-Spinners e-book on my Kindle and also read about the author, finally realizing she had also written The Crystal Cave.

When I was a child, my mother and my spinster aunts read hundreds of Harlequin Romances, which I dismissed as boring trash, although I never actually read one. In 1957, Harlequin had acquired the North American distribution rights to the romance novels published by Mills & Boon in the British Commonwealth. It eventually acquired Mills & Boon and published six novels each month which were sold in supermarkets, drug stores, and the like. My aunts remodeled an entire room of their house, filling it with shelf after shelf of Harlequin Romances. The company has published about 5,000 titles under that imprint but has many others, and it currently publishes over 120 new titles each month in North America and over 800 globally. I wouldn’t be surprised if many of the storylines are now developed with artificial intelligence and eventually are entirely drafted by AI with human proofreader edits.

I have always enjoyed mysteries, and romances have blended into many of them. Given that Mary Stewart is touted as a talented pioneer in romance suspense, and remembering how her first Merlin book was well-written, albeit unable to prompt me to continue that series, I decided to read The Moon-Spinners. I needed a palate cleanser after reading Thornton Wilder’s ponderous The Eighth Day.

The Romance Suspense

Mary Stewart sketched a Cretan windmill for her publisher as a design idea for the book cover. Hodder in the UK used that for its first edition hardback book cover, but I notice that a later paperback edition added a running male figure to the scene and “Nicola — in an island nightmare of terror and pursuit”. Neither were improvements to my eye, but they would have been helpful to casual shoppers, although they are confusing since Nicola is actually the female protagonist of the story and not pictured on the cover. The US cover was similar to the original UK one, but instead of depicting a windmill in the bright Mediterranean sunlight, Charles Geer‘s illustration was dark and moody.

You might think the windmill has something to do with the title, but while a windmill does play some role in the plot, the character of Nicola shares the tale of the moon-spinners to help lull someone to sleep:

They’re naiads – you know, water nymphs. Sometimes, when you’re deep in the countryside, you meet three girls, walking along the hill tracks in the dusk, spinning. They each have a spindle, and onto these they are spinning their wool, milk-white, like the moonlight. In fact, it is the moonlight, the moon itself, which is why they don’t carry a distaff. They’re not Fates, or anything terrible; they don’t affect the lives of men; all they have to do is to see that the world gets its hours of darkness, and they do this by spinning the moon down out of the sky. Night after night, you can see the moon getting less and less, the ball of light waning, while it grows on the spindles of the maidens. Then, at length, the moon is gone, and the world has darkness, and rest, and the creatures of the hillsides are safe from the hunter, and the tides are still . . .

Then, on the darkest night, the maidens take their spindles down to the sea, to wash their wool. And the wool slips from the spindles into the water, and unravels in long ripples of light from the shore to the horizon, and there is the moon again, rising above the sea, just a thin curved thread, re-appearing in the sky. Only when all the wool is washed, and wound again into a white ball in the sky, can the moon-spinners start their work once more, to make the night safe for hunted things . . .

The novel begins with Nicola being dropped off after a car ride at a trailhead to a small Cretan village by the American tourists Mr. and Mrs. Studebaker. It may not have been Stewart’s intention, but I interpreted those as names the protagonist gave to them that merely reflected the make of car they drove.

On her walk toward the village, Nicola pauses at a bridge and then takes a side path up to the villagers’ fields where windmills whirl, pumping irrigation water through the ditches. She then opts to follow an egret up a ravine. Stewart’s writing is evocative:

For some reason that I cannot analyse, the sight of the big white bird, strange to me; the smell of the lemon flowers, the clicking of the mill sails and the sound of spilling water; the sunlight dappling through the leaves on the white anemones with their lamp-black centres; and, above all, my first real sight of the legendary White Mountains . . . all this seemed to rush together into a point of powerful magic, happiness striking like an arrow, with one of those sudden shocks of joy that are so physical, so precisely marked, that one knows the exact moment at which the world changed.

She ascends the hillside and is soon threatened by a knife-wielding man, tends a man with a bullet wound, and is drawn into ‘skulduggery’. Nicola’s independence and self-assurance are rapidly made evident.

Nicola’s first hint of trouble was a sudden shadow, and near the conclusion of the resulting scene, with the immediate threat vanquished, Stewart adjusts her grip on the reader with Nicola thinking, “Suddenly, out of nowhere, fear jumped at me again, like the shadow dropping across the flowers.”

Her style is light and deft in a speedy first-person narrative that was a welcome contrast to the pontificating third-person prose in the Thornton Wilder novel I had just finished. I was soon 1/8 into the book and struck by how Stewart’s elegant prose elevated scenes reminiscent of the childhood Nancy Drew or Trixie Belden mysteries my spinster aunt loaned me when I had exhausted the Hardy Boys.

While as a kid I was fine with the minimal involvement of the teenage sleuths’ nearly invisible romantic partners, I quickly sensed that in this story the 22-year-old Nicola might well end up romantically entangled with Mark, the young man who had been shot, even though Stewart was careful not to overplay their initial introduction.

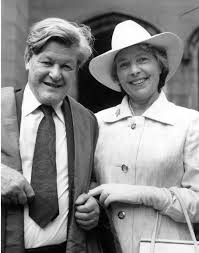

Mind you, Stewart moved fast in her own romance. Elsie of the Tea & Ink Society shares this: “Mary met her husband Frederick at a Victory in Europe Day celebration dance in 1945. It was a costume party, and Frederick was unselfconsciously wearing a girl’s gym tunic, lilac socks, and a red hair ribbon. It was pretty much love at first sight, and the couple were married three months later.”

Stewart begins each chapter with a brief literary excerpt. For Chapter 3 she selected, “When the sun sets, shadows, that showed at noon but small, appear most long and terrible.” That is drawn from Nathaniel Lee and John Dryden’s 1679 adaptation of Sophocles’ Oedipus. A fuller quotation is:

When the Sun sets, Shadows that shew’d at Noon

But small, appear most long and terrible;

So when we think Fate hovers o’er our Heads,

Our Apprehensions shoot beyond all Bounds,

Owls, Ravens, Crickets seem the Watch of Death,

Nature’s worst Vermin scarce her godlike Sons,

Echoes, the very Leavings of a Voice,

Grow babling Ghosts, and call us to our Graves:

Each Mole-hill Thought swells to a huge Olympus,

While we fantastick Dreamers heave and puff,

And sweat with an Imagination’s Weight;

As if, like Atlas, with these mortal Shoulders

We could sustain the Burden of the World.

Heady stuff!

Stewart’s descriptions of the settings were superb. I could readily visualize them, thanks to paragraphs like this:

The place he chose was a wide ledge, some way above the little alp where the hut stood. As a hiding place and watch-tower combined, it could hardly have been bettered. The ledge was about ten feet wide, sloping a little upwards, out from the cliff face, so that from below we were invisible. An overhang hid us from above, and gave shelter from the weather. Behind, in the cliff, a vertical cleft offered deeper shelter, and a possible hiding-place. A juniper grew half across this cleft, and the ledge itself was deep with the sweet aromatic shrubs that clothed the hillside. The way up to it was concealed by a tangling bank of honeysuckle, and the spread silver boughs of a wild fig tree.

The story zips along at a fairly rapid clip, with Nicola showing no hesitation in staying overnight to care for the wounded man with a murderer on the prowl, with the next 1/8 of the novel spent on the mountainside avoiding his search. Nicola reaches the village 1/3 of the way into the story and immediately starts to piece together the puzzle.

Nicoloa’s much older female cousin appears, as the character herself phrases it, “at half-time”, and I appreciated this description of her: “Some people, I know find her formidable; she is tall, dark, rather angular, with a decisive sort of voice and manner, and a charm which she despises, and rarely troubles to use.”

The story includes a major red herring, so Stewart does not shy away from manipulating the reader. Overall, I enjoyed the novel, although I did not discern deeper meanings in it beyond a fun adventure, and it lacked the emotional depth and connection that Edith Pargeter could bring to some of her characters in the Brother Cadfael and Inspector Felse mysteries. The first person narrative sometimes shifts plot points into remote retrospectives that are relayed, not related, to the reader. I didn’t find Stewart’s tale particularly romantic, with little time given for Nicola and Mark to develop any sort of relationship beyond trying to protect each other and implausible feats of derring-do, although the settings were suggestive.

I regard the work as a well-written adult version of a Nancy Drew mystery with superb travelogue elements. I’m certainly willing to read more of Stewart’s romance suspense stories, but I would only expect them to be light reads that serve as quick escapes and palate cleansers.

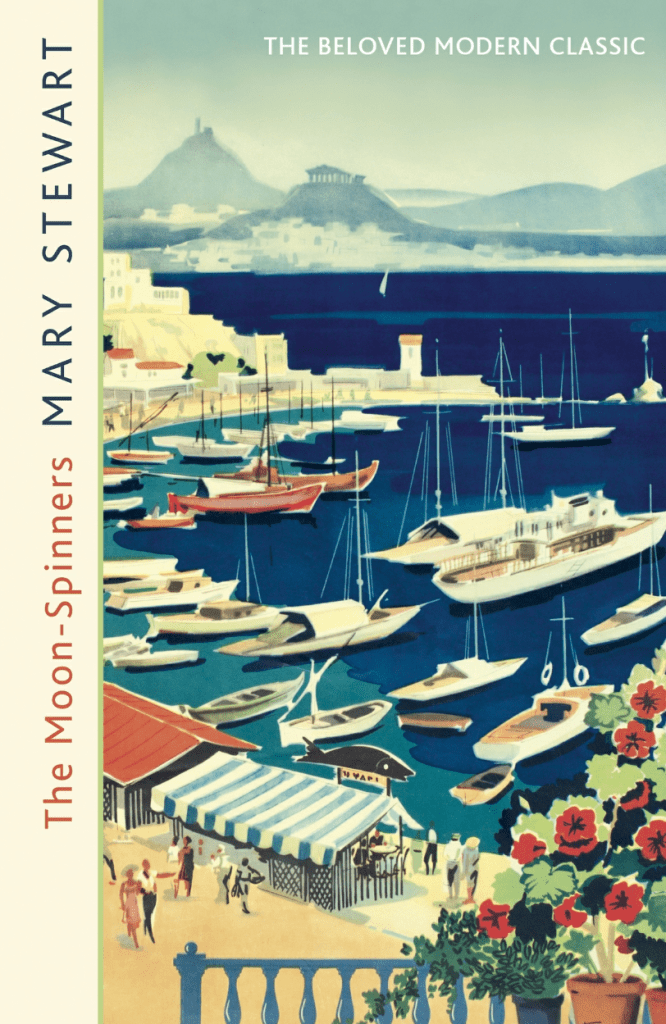

Publishers Hodder & Stoughton have reissued much of Mary Stewart’s fiction under the Beloved Modern Classics label, at least in Kindle editions. I appreciate their beautifully restrained cover designs featuring illustrations that resemble travel posters.

Given her evocative descriptions of the settings, her standalones seem well-suited to armchair travelers. This fast-paced adventure set on the sunny isle of Crete would have been especially welcome on a cold wintry day.

Stewart wrote 15 standalone novels in the romance suspense genre, separate from her five Arthurian books. Elsie of the Tea and Ink Society says, “Her earlier books supply greater drama and thrills and are more Gothic in tone, while her later novels are gentler but still masterfully plotted.”

For both yours and my reference, here is Elsie’s listing with her Amazon links and brief descriptions of Stewart’s standalones:

Madam, Will You Talk? (1955) – set in Provence, France

Wildfire at Midnight (1956) – set on the Isle of Skye, Scotland. Murder mystery elements.

Thunder on the Right (1957) – a Gothic novel set in the Pyrenees in France

Nine Coaches Waiting (1958) – elements of Gothic, fairy tale, and fugitive story. Set in the mountainous Savoy region of France.

My Brother Michael (1959) – set in mainland Greece

The Ivy Tree (1961) – an impostor/mistaken identity story set in Northumberland, England

The Moon-Spinners (1962) – set in Crete

This Rough Magic (1964) – set in Corfu

Airs Above the Ground (1965) – a murder mystery with a touch of espionage, set in Austria

The Gabriel Hounds (1967) – set in Syria and Lebanon

The Wind Off The Small Isles (1968) – a novella set in the Canary Islands, Spain

Touch Not the Cat (1976) – set in the Malvern Hills in the West Midlands of England. Fantasy/supernatural elements.

Thornyhold (1988) – set in Wiltshire in South West England. Fantasy/supernatural elements.

Stormy Petrel (1991) – set on a fictional island in the Hebrides of Scotland

Rose Cottage (1997) – a gentle mystery of family secrets, set in a small village in the North of England

Stewart’s quick story was most welcome after my failing to complete V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas and reading Thornton Wilder’s remote The Bridge of San Luis Rey and stolid The Eighth Day, but I’m not ready to tackle more “literature” just yet.

As I compose this post, I am still listening to film director William Friedkin’s splendid memoir on my weekend walks, so I want to stick with fiction in my physical or electronic book reading for now. My Kindle collection still has five unread Ellis Peters novels, along with a couple of novellas and sixteen short stories, but I’m not ready for another mystery, either.

So, since it is now Banned Books Week, I’ve started Tim Huntley’s little-known 1980 novel, One on Me, a science fiction pulp paperback I bought at the end of 2023 after Bookpilled cited it as funny but having some controversial content. I doubt there were ever enough copies in circulation to get it banned, but it certainly would offend the blue-nosed bullies.