Time and tide tarry for no one, and both are on my mind these days due to the political change that is transforming our republic. The United States of America has the oldest continuously operating written constitution, but its structures are being rapidly eroded by a tide of populism. Be forewarned that I am going to share my perspectives on that in this post, so skip it if that is not your thing.

I am far more hesitant about political posts than I once was, given the polarization driven by social media algorithms that increase engagement by amplifying posts that are emotionally charged. Also, Oklahoma is still dominated by evangelical Christians, and over my six decades they have become far more politically active and aligned with the Republican party. If people conflate political stances with religious beliefs, that can supercharge disagreements.

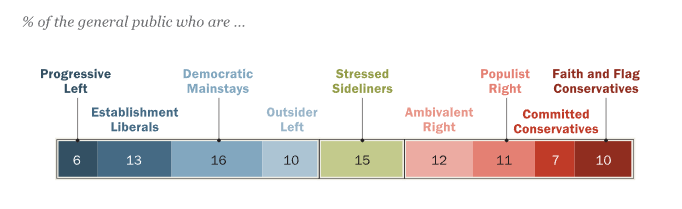

This post reflects my biases, so know that I am among the oldest members of Generation X, and my political typology is that of Outsider Left in the Pew Research Center’s Political Typology Quiz. 90% of my fellow citizens are of a different political type, and that’s A-OK. Given Oklahoma’s partially closed primary system, I routinely change my party registration between Democrat and Republican as needed to allow me to vote for more moderate candidates in primary elections. Like George Washington, I consider political parties the bane of our republic.

- My Ground Rules:

- This is my personal blog, not a debate forum. I am not interested in debating politics or religion with you here or on social media. Hence I turned off comments for this blog post. If you want to argue with someone, you’ll find willing victims in abundance on social media.

- I am not seeking to evangelize here, but instead to share my possibly idiosyncratic takes, in my own detailed fashion, for those who are interested.

- I fully support your right to disagree or disengage. There is plenty else on the internet, and in this blog, that might be more to your liking.

- Finally, as always, nothing here in any way reflects the views of my employer — and I’m grateful that in July 2026 I’ll be retiring from employment and consequently the need for such a disclaimer.

Our enduring political heritage

Our system of government was a product of The Age of Enlightenment which promoted ideals of individual liberty, religious tolerance, progress, and natural rights, being heavily influenced by the Scientific Revolution as well as the trauma from centuries of religious conflict in Europe.

The founders crafted a constitutional system of checks and balances among three branches of government that endured, mostly intact, for well over two centuries. The genius of amendments gave it the needed flexibility to evolve as our nation’s practices slowly and unevenly approached its ideals.

The most painful correction led to the Civil War, when well over 600,000 people were sacrificed in the struggle to end the Constitution’s original sin of chattel slavery. Later notable improvements included expanding rights for women, First Peoples, and, within my lifetime, various ethnic and sexual minorities.

Our system of government survived the rise of autocratic regimes which plagued most of the world across the 20th century, but not without sacrifices. The U.S.A. lost 117,000 people in the first World War, which led to the collapse of the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Russian empires.

[Source]

My father served in World War II in the struggle against Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan, which claimed over 400,000 of his countrymen. I grew up during the Cold War, amidst the détente with the Soviet dictatorship enforced by mutually assured destruction.

Populism

Populism is an anti-establishment approach to politics which views “the people” as being opposed to “the elite”. It shares those characteristics with fascism, but fascism is distinct in its obsessive focus on national or racial purity and aggression. Also, while there are both liberal left-wing and conservative right-wing forms of populism, fascism is inherently right-wing.

While a significant majority of Republicans today embrace fascistic treatment of illegal immigrants, much of the party’s behavior, and its ascendency, are better understood as consequences of it being consumed by populism, not fascism.

In the U.S.A., populism reaches back to the presidency of Andrew Jackson in the 1830s and blossomed again as the People’s Party in the 1890s, with William Jennings Bryan as one of its famous figures. White settlers brought that populist movement from Kansas into Oklahoma in the land runs of the late 1800s. While the People’s Party faded rapidly after 1896, Oklahoma’s 1907 constitution contained various populist components, including popular election of all officeholders, an initiative and referendum process, and a corporation commission.

Later notable populists were Louisiana’s Huey Long, Alabama’s George Wallace, Ross Perot, and Sarah Palin. Currently Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders are populists on opposite ends of the political spectrum.

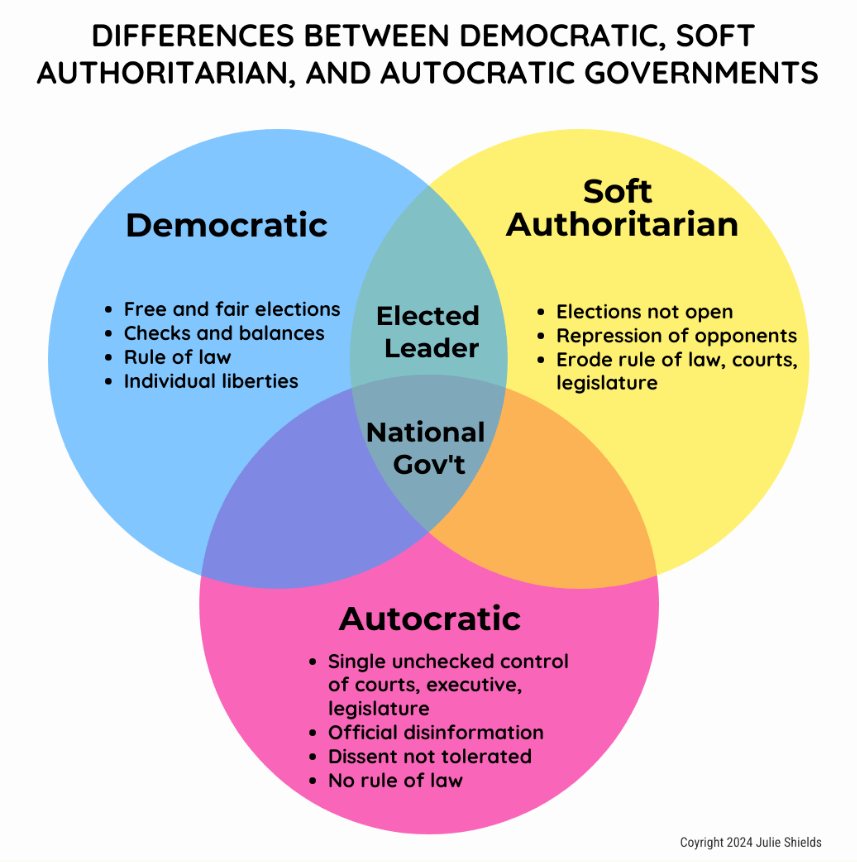

One of the dangers of populism, both in its left-wing and right-wing forms, is that it undermines democratic institutions, erodes social cohesion through its “us” versus “them” mentality, and often leads to negative economic consequences and violations of human rights.

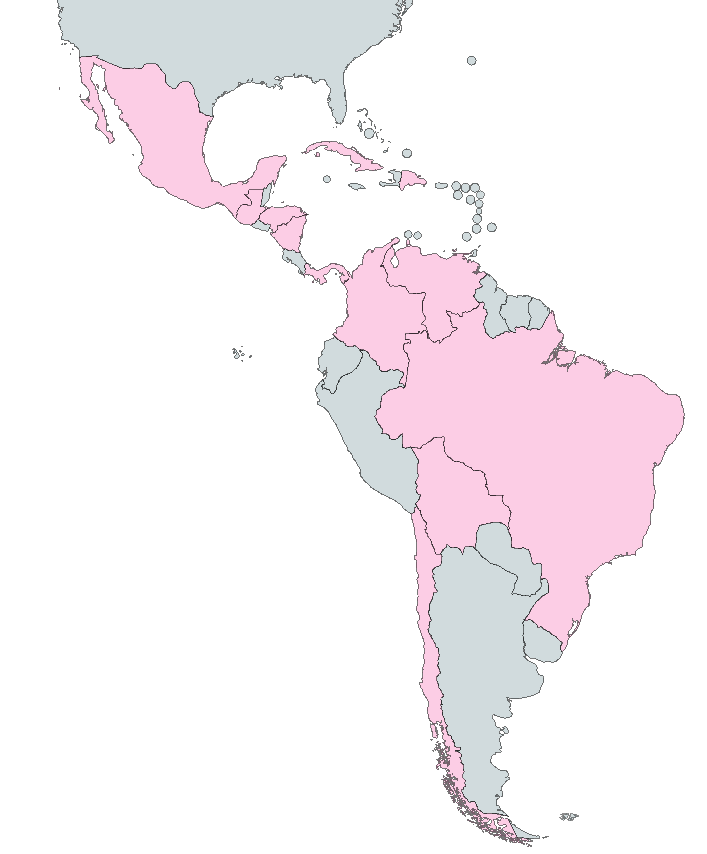

A populist tide rose across the world in the 21st century. In the Americas south of the U.S.A., it manifested as a “pink tide” of left-wing governments extending from Mexico across Central and South America that has cyclically waxed and waned. Several of the new governments were authoritarian, while others remained democratic.

In Europe, populist movements empowered Viktor Orbán in Hungary, the Law and Justice party in Poland, and Brexit, the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union.

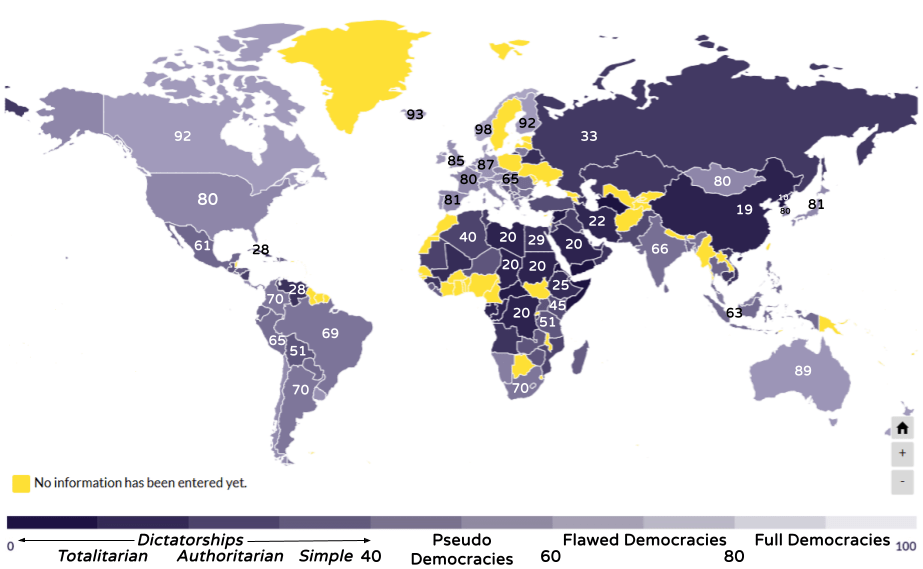

The European Center for Populism Studies has crafted a world map in which darker shades of purple indicate weaker democratic institutions and norms, with numerical ratings on a scale from dictatorships to full democracies, based on a country’s performance across fundamental human rights, civil liberties, rule of law, and elections.

[Source]

In their ratings, the United States of America is on the verge of slipping from full to flawed democracy. Our democratic institutions and norms now fall below those of Canada, northern Europe, and Australia.

The end of norms

Donald Trump openly undermines democratic institutions, discredits opponents, and erodes the rule of law. He has been empowered by the ever-increasing polarization of the populace, and thus Congress, and the collapse of the Republican establishment’s foundations of sand, which were swept away by the populist tide.

That populism explains why Republican politicians have abandoned past conservative stances that stressed state rights and the separation of powers while promoting free trade and a pretense of fiscal discipline. The seeming cognitive dissonance or hypocrisy of championing state rights in the causes of abortion restrictions yet embracing the use of troops for immigration enforcement is less surprising once you recognize that the Republicans are now more populist than truly conservative.

Populism also explains Trump’s virulent attacks on science, public health, mainstream media, entire governmental divisions, and higher education. Trump and his supporters leverage the real and earned resentments of the working class, but not to provide tangible benefits to their supporters but instead to destroy institutions and cultural norms associated with a rival, progressive elite.

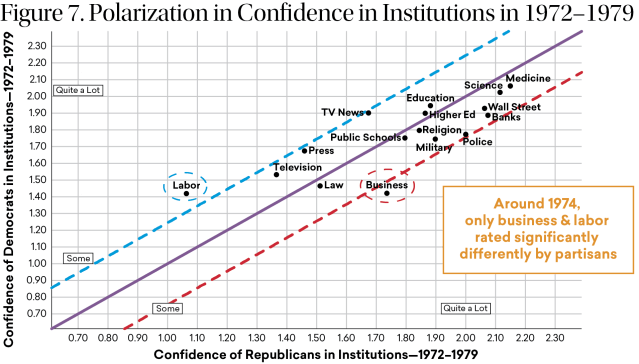

It is illuminating to examine the political polarization in confidence in our various institutions. Consider this chart of Democrat and Republican confidence in the 1970s, when there wasn’t much difference between their trust in most institutions save for Democratic confidence in labor versus Republican confidence in business:

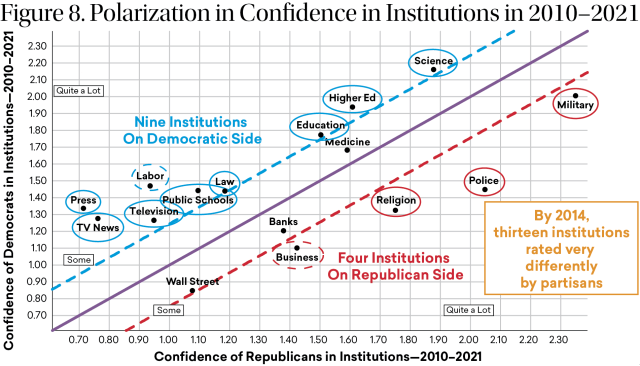

Compare that to the 2010s, when Democrats had more confidence in knowledge-producing institutions while Republicans had more confidence in order-preserving ones.

Now consider which institutions Trump has decimated, with the Republicans in Congress mostly acquiescent even when that damages their own constituencies’ long-term interests.

Why is populism ascendent?

I am a fan of the political and cultural commentator David Brooks. He composed a compelling narrative to explain the populism of the working class:

This story begins in the 1960s, when high school grads had to go off to fight in Vietnam but the children of the educated class got college deferments. It continues in the 1970s, when the authorities imposed busing on working-class areas in Boston [and OKC] but not on the upscale communities like Wellesley [and OKC suburban districts] where they themselves lived.

The ideal that we’re all in this together was replaced with the reality that the educated class lives in a world up here and everybody else is forced into a world down there. Members of our class are always publicly speaking out for the marginalized, but somehow we always end up building systems that serve ourselves.

The most important of those systems is the modern meritocracy. We built an entire social order that sorts and excludes people on the basis of the quality that we possess most: academic achievement. Highly educated parents go to elite schools, marry each other, work at high-paying professional jobs and pour enormous resources into our children, who get into the same elite schools, marry each other and pass their exclusive class privileges down from generation to generation.

Armed with all kinds of economic, cultural and political power, we support policies that help ourselves. Free trade makes the products we buy cheaper, and our jobs are unlikely to be moved to China. Open immigration makes our service staff cheaper, but new, less-educated immigrants aren’t likely to put downward pressure on our wages.

Like all elites, we use language and mores as tools to recognize one another and exclude others. Using words like “problematic,” “cisgender,” “Latinx” and “intersectional” is a sure sign that you’ve got cultural capital coming out of your ears. Meanwhile, members of the less-educated classes have to walk on eggshells because they never know when we’ve changed the usage rules so that something that was sayable five years ago now gets you fired.

We also change the moral norms in ways that suit ourselves, never mind the cost to others. For example, there used to be a norm that discouraged people from having children outside marriage, but that got washed away during our period of cultural dominance, as we eroded norms that seemed judgmental or that might inhibit individual freedom.

After this social norm was eroded, a funny thing happened. Members of our class still overwhelmingly married and had children within wedlock. People without our resources, unsupported by social norms, were less able to do that.

It’s easy to understand why people in less-educated classes would conclude that they are under economic, political, cultural and moral assault — and why they’ve rallied around Trump as their best warrior against the educated class. He understood that it’s not the entrepreneurs who seem most threatening to workers; it’s the professional class. Trump understood that there was great demand for a leader who would stick his thumb in our eyes on a daily basis and reject the whole epistemic regime that we rode in on.

The Democrats once enjoyed strong support from the working class, thanks to their old alignment with labor and the Republicans’ long-term alignment with business interests. But the very successes of unions — the 40-hour workweek, minimum wage, child labor laws, worker’s compensation, workplace safety laws — were secured long before most of us were born. Those successes promoted the growth of the middle class, but with such rights secured, unions began to fade away with the decline of manufacturing, the rise of the service economy, and economic recessions.

Since the 1970s, central features of our politics have been social, cultural, and racial issues. That has affected our beliefs about institutions. Professions have become more ideologically homogenous and extreme, which in turn has fueled partisan distrust. Henry E. Brady of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences shared:

On a 2019 survey, we asked respondents how they would feel about someone close to them choosing a career or marrying someone involved with various institutions. We were shocked and surprised to find that Republicans do not want their kin or friends to have a close association with journalists or with anyone working in higher education. Democrats do not want close connections with anyone in the police, the military, or religious institutions.

Constitutional erosion

The first Trump impeachment failing to result in a conviction was not surprising, given that the prior impeachments of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton failed to yield convictions.

The failure to convict in his second impeachment, after his disruption of the peaceful transfer of power for the first time in the nation’s history, was far more disturbing. That confirmed that populism had taken control of the Republican party, with 43 of the 50 Republican senators abandoning their oaths to support, defend, and bear true faith and allegiance to the Constitution by failing to prevent Trump from running again for the office he had betrayed. No doubt many of them felt that if they stood up for the Constitution their own populist base would consequently turn them out of office: a few days after the attack on the Capitol, over 3/4 of Trump voters, and about 1/3 of all voters, believed “the big lie” that Biden’s election was illegitimate.

Operational norms were mostly reinstated for a few years under Biden, but then his personal hubris led him to betray his party’s and the national interest. Instead of stepping aside to support a healthy Democratic primary process that might have identified a Presidential candidate who could appeal to liberals, moderates, and some populists, he wanted a second term. When his declining abilities made that impossible, the Democratic party made the elitist and fatal choice to have a black woman as its presidential candidate amidst a populist tide in a country in which both racism and sexism remain commonplace. Their blinkered identity politics ensured that Trump, despite his crimes, cruelty, and advanced age, won both the popular and electoral votes.

Thus far in Trump’s second term, Congress, with slim Republican majorities in both the House and Senate, has completely capitulated to the executive. The President routinely violates the law, and Madison’s plan that “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition”, harnessing the natural jealousy and ambition of political actors to prevent any one branch of government from becoming too powerful, has failed.

Many of the Republicans in Congress were elected as populists, and some of them simply do not believe in government. That is why they are quite effective at destroying programs and institutions yet repeatedly fail to produce promised alternative plans for health care, infrastructure, or other common interests. Their primary achievements are continuing tax cuts, despite the consequent explosive growth in the national debt.

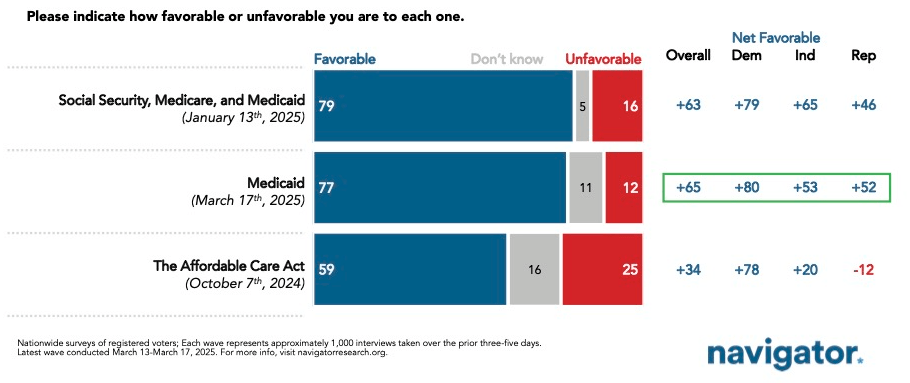

A portion of them genuinely believe in the long-discredited theories of trickle-down economics, while others no doubt hope that the unsustainable debt will eventually force the curtailment of the Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid entitlements and further weaken the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Bear in mind that the GOP opposed the creation of all of those programs, which enjoy broad overall support. Only the ACA has a net unfavorable rating among Republican voters, but Republicans in Congress still passed legislation that will result in millions of people losing Medicaid coverage, and they joined Democrats in continuing to ignore the depletion of the Social Security Trust Fund in 2033.

Republicans know that most of their policy goals would not survive senatorial filibusters. They could vote to further weaken or fully eliminate the filibuster, but that would in turn make them vulnerable when their control of the Senate slips. So they have adopted a long-term strategy of allowing the executive to illegally enact their policy goals. Their hope is that, whenever the Democrats eventually do regain majorities in Congress and control of the White House, the Democrats’ more diverse and moderate coalition would be restrained by the filibuster and the rule of law.

Also, by allowing Trump to accomplish their policy goals by fiat, they avoid direct votes that would attach to them blame for his various destructive acts that will inevitably have significant negative long-term consequences.

The considerable cost of that strategy is how it empowers a cruel and incompetent executive branch and accelerates the slide into competitive authoritarianism. While authoritarianism appeals to many people who value short-term action over long-term stability, it inevitably lowers economic growth and restricts civil rights and liberties.

One reason the Republicans in Congress are allowing the executive branch to violate the law and the Constitution is their misplaced trust that the judicial branch will eventually contain the worst excesses. However, the machinations of Mitch McConnell that created a supermajority of right-wing Supreme Court justices has severely undermined the judicial branch’s legitimacy and enforcement of the rule of law. The unitary executive theory that a majority of the court now embraces is a concentration of executive power that betrays the clear vision and intent of the founding fathers, who deliberately made the legislative branch the most powerful. It is also at odds with why the American Revolution was fought.

The increasingly unmoored reasoning of the partisan Supreme Court has freed the president from the rule of law, but even that might not suffice for Trump. His administration could become more brazen in its repeated violations of lower court orders and, if the Supreme Court eventually ends its campaign of appeasement, he might refuse to follow its rulings.

If that happens, the only remaining Constitutional tool to constrain him would be his impeachment in the House and conviction in the Senate, which is unlikely given that most Republicans in Congress have already abandoned their oaths. A military coup is unlikely, so I expect that it would require massive civil unrest to overturn Trump’s authoritarian regime in such a scenario.

However, I do not actually expect Trump to be so deranged. My prediction is that he will continue to flaunt his power while avoiding too direct a confrontation with the judicial branch. His corruption of the government has already enriched him greatly, and he will grant himself and his cronies pre-emptive federal pardons when he leaves office. His narcissism leads him to expect to continue to elude justice, and I expect he might, as our legal system has always been too slow, corrupt, and politicized to hold him to account. His greatest enemy is time in the form of his ongoing physical and mental decline.

A longer view

There is also the long-term issue that while Trump’s charisma, brazenness, and demagoguery have channeled the populist tide to power his pulverizing mill, his departure from office and eventual death will not dissipate it. The class resentment he manipulated will remain a potent force that future charismatic demagogues could wield.

Democrats remain disorganized, and they are distinctly and deservedly unpopular. Their best hope for retaking parts of the federal government is that the economic shocks of Trump’s policies will trigger a significant recession in 2026 or 2027. Of the eleven recessions after World War II, ten occurred under Republican presidents. Republicans rely far too heavily on tax cuts and deregulation for economic growth, while Democrats are usually more pragmatic in heeding economic and historical lessons.

However, I expect little long-term success for Democrats so long as they continue to fail to recognize and harness the energy of the populist tide. Their coalition relies far too much on minority identity politics, is out of touch on cultural issues, alienates young men and rural voters, and is more reactive than visionary in directly addressing more problems of the working class.

David Brooks highlighted the populist problem for me, and he posits that America’s historical distinction from class-driven Europe could be parlayed into a counter-narrative to Trumpism that rejects class conflict and embraces social mobility. He notes that, “Trump’s ethos doesn’t address the real problems plaguing his working-class supporters: poor health outcomes, poor educational outcomes, low levels of social capital, low levels of investment in their communities, and weak economic growth.”

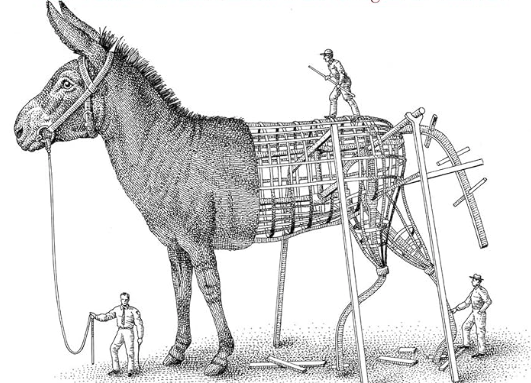

He points out how the Populist Progressive movement of the late 1800s was a response to the political corruption, concentration of corporate power, huge inequality, and racial terrorism of that period. Progressives in big cities and populists in small towns “wanted to help those who were being ground down by industrialization” and “believed in using government to reduce inequality and expand opportunity.” He wonders if a new coalition could help us cope with the rise of the Information Age, reforming our universities, Congress, corporations, the meritocracy, and the new technocracy.

Brooks envisions an alliance that is “economically left, socially center right, and hell-bent on reform” and rejects the endless class and culture wars. However, he also points out one of the bleak realities of our age: “Americans have at most a two-week attention span, so to control the conversation, you need to stage a series of two-week mini-dramas, each with high-stakes confrontations and surprises.” Any counter-movement may have to become part of that depressing milieu.

Brooks closes his essay by noting that America’s cyclic process of rupture and repair follows a sequence: “Cultural and intellectual change comes first — a new vision. Social movements come second. Political change comes last.”

All that takes time, and I am genuinely concerned that the stable government I grew up with, featuring bipartisanship, general respect for the rule of law, a belief in and agreement with the deeper operating principles of our constitution, and a hope for a better tomorrow might not return in the few decades I hope to endure.