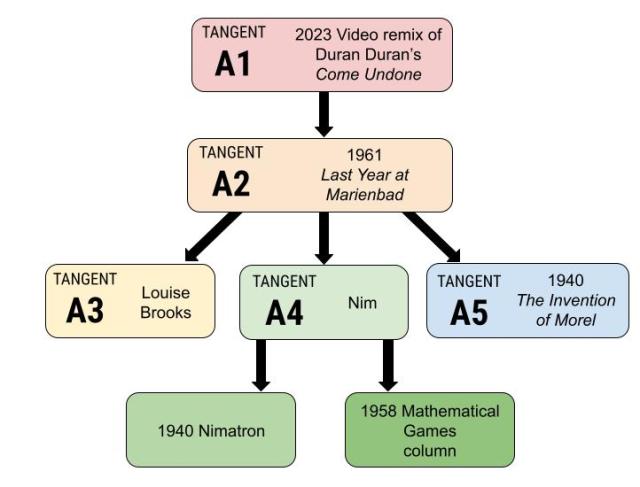

This is the fourth of five snowed-in posts, illustrating the pathways I sometimes pursue due to my avid curiosity. This Tangent began with a video remix of an old song by Duran Duran, which had inserts from the French New Wave film Last Year at Marienbad. That film featured the two male protagonists repeatedly playing the ancient game of Nim.

True to form, the obscure film did not provide the name of the game, but the principles were clear enough:

The game might have originated in China and some say it resembles 捡石子 or “picking stones” while the earliest European references are reportedly from five centuries ago. Charles L. Bouton of Harvard gave it the name of Nim, and he developed the complete theory of the game in 1901. In the film, it is played as a misère game where the player with the last game piece loses, but many variants are possible.

Throughout the movie, Nim is played with cards, matchsticks, chips, dominos, and at least set up for play with photographs. You can play it here.

Martin Gardner wrote about Nim in his Mathematical Games column in the February 1958 issue of Scientific American, illustrating how binary math could determine how to play a perfect game. Edward Condon, who later would be better known for his leadership of a committee explaining away UFOs, co-invented an electromechanical machine consisting of 116 relays, over two miles of copper wire, weighing over 2,200 pounds, that could play Nim: the Nimatron.

Westinghouse Electric built the device, which played 100,000 games at the New York World’s Fair in 1940, winning 90,000 of them. Condon deliberately introduced delays in its computations to avoid discouraging human players, and it was only programmed with a certain number of predetermined games to allow humans a chance to beat it. Most of the losses were to attendants who had learned how to beat the machine in order to discredit complaints that the machine was unbeatable.

Condon designed the Nimatron merely for amusement, failing to recognize the potential of his patent for it that described an internal representation of numbers, a concept that would be critical in the forthcoming computer revolution.

Roland Sprague in 1935 and Patrick Michael Grundy in 1939 independently developed the theorem that all impartial two-player games can be equivalent to a game of Nim.

Here’s a video on how to win at Nim:

I earned straight A’s in all of my math classes, making it through all the semesters of calculus and ordinary and partial differential equations in college and only narrowly avoiding a minor in mathematics. However, math was anything but my easiest or favorite subject. For me, it was always a means to an end, and I can’t feign enough interest in Nim to master its theory.

Similarly, I’m not motivated to try to “solve” Last Year at Marienbad, which was deliberately left open to multiple solutions. In the film, the “husband” of the female lead instigates the game plays, and he always wins. It is clear that his various opponents, including the man gaslighting the woman, do not know the winning strategy. They fumble around, while he knows all the outcomes in advance.

The ending of the movie leaves you wondering if he did not also already know the predetermined loss of the woman. Is the hotel purgatory and the “husband” a representation of death? Perhaps his inherent inevitability explains his remark, “Oh, I can lose, but I always win.”

Or is his apparent loss at the end actually a win? Is he playing a misère game with the woman as the final game piece? There are no solutions, no answers. As Roger Ebert said, “Answers are a form of defeat.”

Another aspect of the film that aroused my curiosity was what influenced its writing and execution. The homage to Louise Brooks is explained by the revival of interest in her silent film career among French critics in the mid-1950s. However, that is purely surface. A greater literary influence, something one should always look for in a Left Bank film, was an Argentine science fiction novella of 1940, the final Tangent in this series.