December 20-22, 2023 | Photo Album

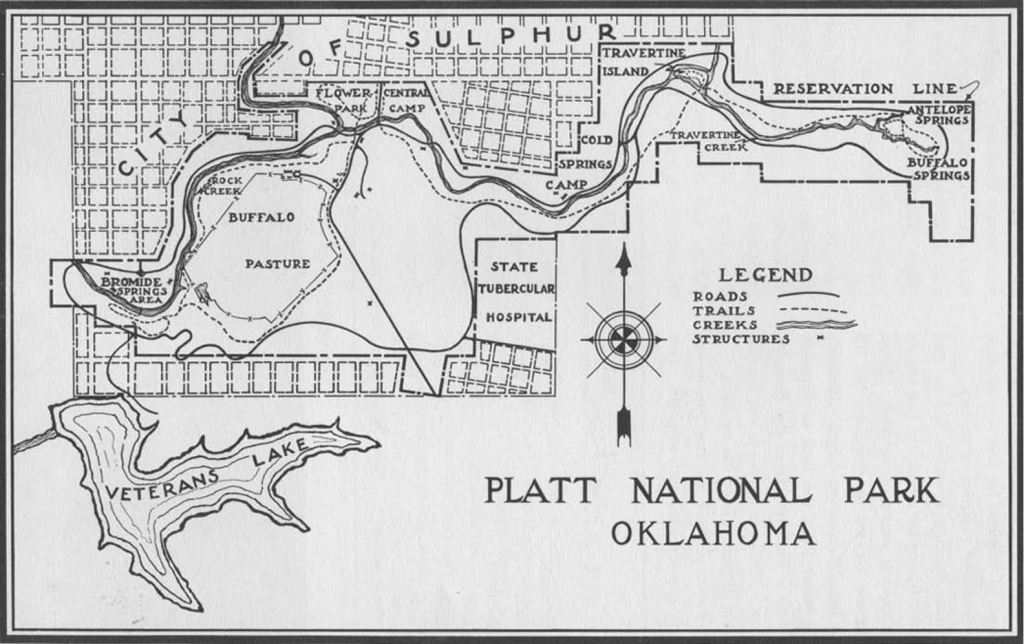

Sulphur Springs Reservation was established in the Chickasaw Nation of Indian Territory in 1902, and it became Platt National Park in 1906. Its national park status was dependent on a deal made with the Chickasaws and Choctaws, who had seen what had happened to the similar hydrotherapy area of Hot Springs in Arkansas. Private entrepreneurs were allowed to build and operate bathhouses there, and the tribes feared they would lose access to the waters of Sulphur Springs unless it was protected.

The city of Sulphur developed directly north of the park, which in the 1930s boasted eighteen sulphur, six freshwater, four iron, and three bromide springs.

The popularity of hydrotherapy waned as more effective treatments were developed for psychological and physical ailments. But Platt remained a popular camping spot, thanks to improvements made by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s.

Robber’s Roost is a lookout 140 feet above Sulphur on Bromide Hill, and the park’s principal mineral springs once issued from its base. Before I was born, my father and mother visited it with my maternal grandmother and three of my mother’s siblings.

Platt was always a target for removal from the National Parks system, with Secretaries of the Interior recommending in 1913, 1925, and 1933 that it be given to Oklahoma and made into a state park. In 1976 Oklahoma finally lost its only National Park when Platt was combined with the Arbuckle Recreation Area and renamed the Chickasaw National Recreation Area.

In the 1970s, my parents would tow their Yellowstone trailer to what we still called Platt to camp in the Rock Creek area just west of Bromide Hill, a campground which had been developed from 1950 to 1967.

Recently I came across a 1977 photograph of myself on Robber’s Roost atop the hill, and that prompted me to suggest to Wendy that we return to Sulphur for a brief visit at the start of our 2023 Winter Break. I had introduced Wendy to Sulphur a decade earlier, and we had returned during Spring Break in 2019.

We set out from Bartlesville on the first day of Winter Break, enjoying lunch at Kilkenny’s in Tulsa before heading down the Turner Turnpike/Interstate 44, exiting at Stroud.

Seminole

For our trip to Sulphur in 2019, after passing through Prague we enjoyed diverting westward to Shawnee to tour its art museum and railroad depot. This time we simply drove due south through Seminole, home of First Peoples who were forcibly relocated from Florida in the first half of the nineteenth century.

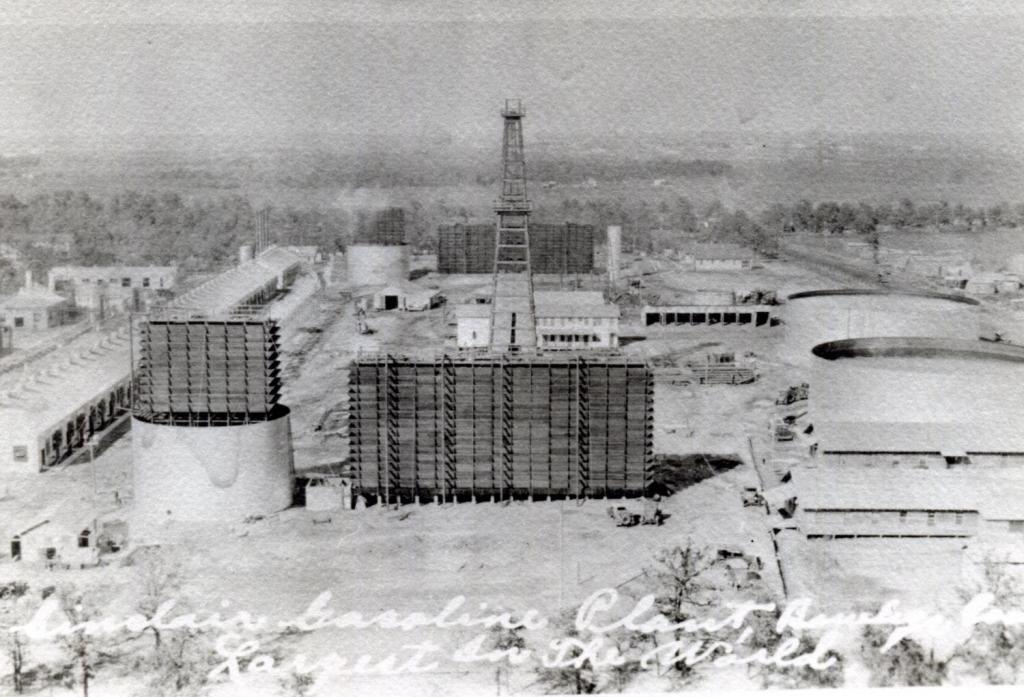

There were originally 24 towns in the Seminole Nation established in Indian Territory in 1856. In 1892 the Seminole government was dissolved and the nation’s territory divided among three thousand enrolled tribe members. Rampant fraud led to only about 20% of the Seminole lands remaining in Seminole hands by the 1920s, when Seminole county became for a brief time the greatest oil field in the world, producing 2.6% of the world’s oil.

In 1926, Seminole boomed from 854 to over 25,000. The town became a morass of mud.

Railroad traffic grew so much that on March 18, 1927 the Seminole yards handled over 24,000 freight cars.

A few Seminoles became wealthy, but most of the riches went to whites. The boom was over by the mid-1930s, and the population stabilized at about 11,000 from 1930 to 1960, but then collapsed to less than 8,000 by 1970 and was 7,146 in 2020, when 20% of its population was below the poverty line. Today, over 13,000 of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma’s 18,800 enrolled citizens live in Oklahoma. Thirty years ago, the Jasmine Moran Children’s Museum was established; it is the town of Seminole’s biggest attraction.

Bowlegs

Five miles south of Seminole is Bowlegs, another oil boom town. But when they built highway 377, it bypassed Bowlegs, and there isn’t even a sign on 377 telling you to turn east for about a quarter-mile on highway 59 to reach the notorious former boomtown.

The Indian Territory Illuminating Oil company (ITIO) brought in the first well there in 1926, and the town grew to about 15,000. ITIO was formed in 1901 and was run by H.V. Foster and Theodore Barnsdall, oil barons familiar to folks where we live in northeast Oklahoma. ITIO was a leader in the oil fields of the Osage reservation, Seminole, and Oklahoma City, and was absorbed into Cities Service by 1940.

The town’s name may have come from Billy Bowlegs, a leader in the Seminole wars when the tribe was still in Florida, and that name might be a corruption of Bolek, an earlier Seminole chief. Billy’s tribal name was Holata Micco, meaning Alligator Chief.

The boomtown of Bowlegs had a bad reputation, with one dance hall nicknamed “the Bucket of Blood” due to its many brawls.

Bowlegs declined rapidly after the boom, with only 105 residents in 1946. Today about 350 people live there, with 24% of the residents living below the poverty line.

I was pleasantly surprised by the quality of highway 377 from Stroud through Prague to Seminole. It was mostly a four-lane divided highway with little traffic and a good road surface. It was just a two-lane south from Seminole to the Canadian River, expanding again to a divided four-lane for the short drive from there to Ada. We then took the ridiculous two-lane Chickasaw Turnpike from Ada to Sulphur.

Legislators forced Governor Bellmon to build it in the late 1980s. He knew it would be a big money-loser, so he had it built with only two lanes. It was in poor condition by 2002, an albatross that neither the turnpike authority nor the department of transportation wanted. The turnpike’s pavement was finally rehabilitated in 2006. In 2011, the last four miles of it near Sulphur was transferred to the department of transportation, reducing the weird little toll road to 13.3 miles. It collected $896,000 in tolls in 2020, which was about 0.3% of the tolls collected statewide. The Chickasaw earned a bit more than $67,000 per mile that year, while the original 86.5-mile Turner Turnpike from Oklahoma City to Tulsa earned about $850,000 per mile. Back in 1954, voters approved cross-pledging turnpike revenues, so the sensible turnpikes support the rest.

Sulphur

For our previous stays in Sulphur, I booked the Hollywood Suite at The Artesian hotel. This time, I used VRBO to rent a vacation home a few miles outside of town to the west of the Lake of the Arbuckles. So before going to the cabin, we stopped to buy breakfast and lunch groceries at Sooner Foods.

I noticed a portrait hanging on the wall by the checkouts, which told me we were dealing with a family-owned business. The portrait was of James Rae Howe, who established the store in 1954. He owned and operated stores in Sulphur, Davis, and Tishomingo, and he rebuilt the Sulphur store after it was destroyed forty years ago in a fire caused by a lightning strike.

James Rae Howe passed away in 2011, and his son Kemper is now President of the chain. I am pleased to note that Sooner Foods has employed many deaf students at the Sulphur store over the years; Sulphur is the home to the Oklahoma School for the Deaf, and Kemper Howe is a member of the Oklahoma School for the Deaf Foundation.

At our rental home, we were thrilled to find a large Christmas tree in the living room.

Wendy promptly spotted a cat without a tail meowing at us on the deck.

That evening she bought a food-and-water dish and some cat food at the Dollar General for our new feline friend, which she named “Sugar Plum”.

We dined in town for two evenings, at opposing ends of the opulence scale. As we drove through town on our way to the rental, Wendy spotted a Carl’s Jr. and mentioned how she missed eating at them. I had avoided the chain for decades, having been repulsed by its ads of hamburgers dripping sauce on clothing in the 1990s. (I haven’t watched television in years, but reportedly the chain shifted to sexually suggestive ads from 2005 to 2017. I can only imagine.)

So we dined at Sulphur’s Carl’s Jr. franchise. Wendy enjoyed a Famous Star cheeseburger, while I had some chicken tenders.

The following night we enjoyed a meal at Springs at The Artesian that cost three or four times as much. I enjoyed a chicken fried steak with country gravy, mashed potatoes, and green beans, while Wendy had a spicy chicken sandwich, and I made sure that we ordered the honey glazed carrots she has always loved there.

Bromide Hill

The primary activity of our trip was a one-mile hike on Bromide Hill. The weather was a thin overcast in the 60s without too much wind, so it was great for hiking.

We drove up and parked at Robber’s Roost. Junipers around the entry steps had mature seed cones, which look like berries.

Many of the cones/berries had fallen onto the steps at Robber’s Roost.

There, high above Sulphur, I posed for a shot we could later compare to the one taken of me there 46 years earlier.

Wendy then posed for a shot we could later compare to her first visit to the overlook ten years earlier.

Bromide Hill is formed of conglomerate rock of the Vanoss Formation. That material forms the surface of much of the recreation area, with only limited areas having underlying shale and sandstone layers of the Simpson Group.

The first name of the area was “Council Rock,” and the “Robber’s Roost” moniker arose after its use as a hideout for outlaws. Springs along the banks of Rock Creek had a salty taste from bromide in the water, and people took the waters in hopes of curing stomach trouble, nervousness, and rheumatism.

By 1908, over 100,000 people visited the area annually, with many visitors camping in the area for three days or longer, taking the waters. Cliffside Trail was established along the face of Bromide Hill, and in 1912, 4,466 feet of cement walks and stairways were built on the Rock Creek side of Bromide Hill. The walks had iron banister posts and a chain, but the chain soon rusted and flaked onto hikers’ hands. Portions of Cliffside Trail washed away in a flood in 1916.

The postcard shows Bromide Hill sometime after 1916, as it includes an iron bridge that was built over the creek after the 1916 flood. It would be dismantled in 1943 and yielded 25 tons of scrap metal for the war effort.

In 1931, a 200-foot retaining wall was constructed at the base of the hill to prevent erosion from Rock Creek and to provide a hiking trail.

Civilian Conservation Corps Camp 808 was authorized for the park in April 1933. 169 young men were set up in tents by the end of May, with another 25 “local experienced men” who were stonemasons, carpenters, plumbers, and tradesmen to teach and supervise the crews.

The park service’s landscape architects judged the park’s trail system to be “antiquated and totally inadequate” and specified trails be constructed 4.5 feet wide with “careful attention to drainage and appearance and gradient”.

The trail up the hillside was completely rebuilt, replacing “flimsy flights of concrete steps” with a long, stone-walled ramp. An 80-foot retaining wall was installed under Robber’s Roost, and the CCC built an extension to the top of the hill in 1935.

In 1937, the Rock Creek Causeway was built below the west end of Bromide Hill. To this day it provides access to the Robber’s Roost parking area up top as well as to the Rock Creek Campground.

By 1941, visitors were less interested in the mineral waters issuing from the hillside spring. In 1943 the park superintendent reported that the trails suffered from erosion, with the trail to the top of Bromide Hill being the most-used and in bad shape. Drainage repairs were made, and the Bromide Trail along the base was rebuilt in 1952.

The flow of Bromide Springs dried up after 1966, with the last trickle from Bromide Springs for two months in 1973. Stone swales with drainage culverts are located along the cliff side of the trail; some of those were constructed in 1990.

After posing at Robber’s Roost, we took the trail down the north side of Bromide Hill. The stone retaining walls always impress me, along with the rock gutters on the cliff side of the trail.

I clearly recall being intimidated hiking up the long ramping switchback as a child. Thus I led us down the hillside, not up it, to then join the Bromide Trail alongside Rock Creek.

After a 15-minute walk down to the creek, we ventured out onto a pedestrian causeway near the Bromide Pavilion.

We could see the Rock Creek causeway for vehicles to the northwest.

I shot some video of the water flowing in the creek.

Then we walked down to the automobile causeway, where I took a shot of Rock Creek flowing onward to the northwest.

The steep western end of Bromide Hill was to our left as we turned south.

The familiar sign for the turnoff to the Rock Creek Campground was there.

We stayed on the road to the left to gradually wind our way around and up the back side of Bromide Hill. There is no walkway along the road, but it was easy to shift onto the grass shoulder whenever a car approached. That made for a gentle return to the minivan up top.

My tracker informed us that the entire one-mile walk took us 45 minutes, with stops. It was just beginning to mist as we returned to the minivan, reminding us of how rainy it was a decade earlier when I first brought Wendy to the park.

Homeward

Our visit to Sulphur was just a brief getaway. Instead of returning home through Ada, Seminole, and Prague to join the Turner Turnpike at Stroud, we took busy Interstate 35 from Davis north to Norman.

I-35 is quite overloaded south of Norman. Texas is preparing to spend $2.5 billion to widen I-35 to six lanes, with it expanding to eight from Denton to the Oklahoma border within the next 15 years. But Oklahoma only has $492 million in its eight-year plan for widening and improving 35 miles of I-35, whereas there are $3 billion in needs along that 126-mile corridor. In the future, I will consider taking old slow highway 77 to avoid the hectic I-35.

I bought Wendy some shoes at the Brown’s Shoe Fit in Norman, and we had lunch at the old El Chico in Sooner Mall. I ate there regularly throughout college from 1984-1988, when it was Sooner Fashion Mall. The mall was quite busy, which was interesting to see given how our local mall has been moribund for years and over my lifetime I’ve seen the closures of Shepherd Mall and Crossroads in the OKC metro and the Southroads, Eastland, Kensington, and Promenade malls in Tulsa.

We then struggled along I-35 through the metro and then shot along the Turner Turnpike to Tulsa. I’m glad that the Turner will eventually be entirely widened to six lanes to reduce truck jams, but that will take years to accomplish.

We enjoyed our brief excursion to Sulphur, but we will likely hunker down for the rest of the break. Wendy has picked out a 1935 Frank Capra film, a Bette Davis comedy from 1942, and a 1949 Joseph Mankiewicz movie for us to watch. I’ve retaliated with a 1941 Howard Hawks film, an Ealing comedy from 1955, and a Billy Wilder movie from 1961. A couple of them aren’t available to stream on Amazon Prime, YouTube Premium, or iTunes, so I ordered those on optical disc. I am skeptical that we’ll get to them all before we return to work, but we should have fun trying.