Math was usually my most difficult academic subject. That surprises people who know that I was an award-winning high school physics teacher. I think that having to work to earn As in math improved my teaching. I related to students who struggled with algebra and calculus, and the only reason I earned 19 credits in undergraduate math was because I wanted to apply math to model the world via physics. I was all about applied mathematics.

Earliest memories

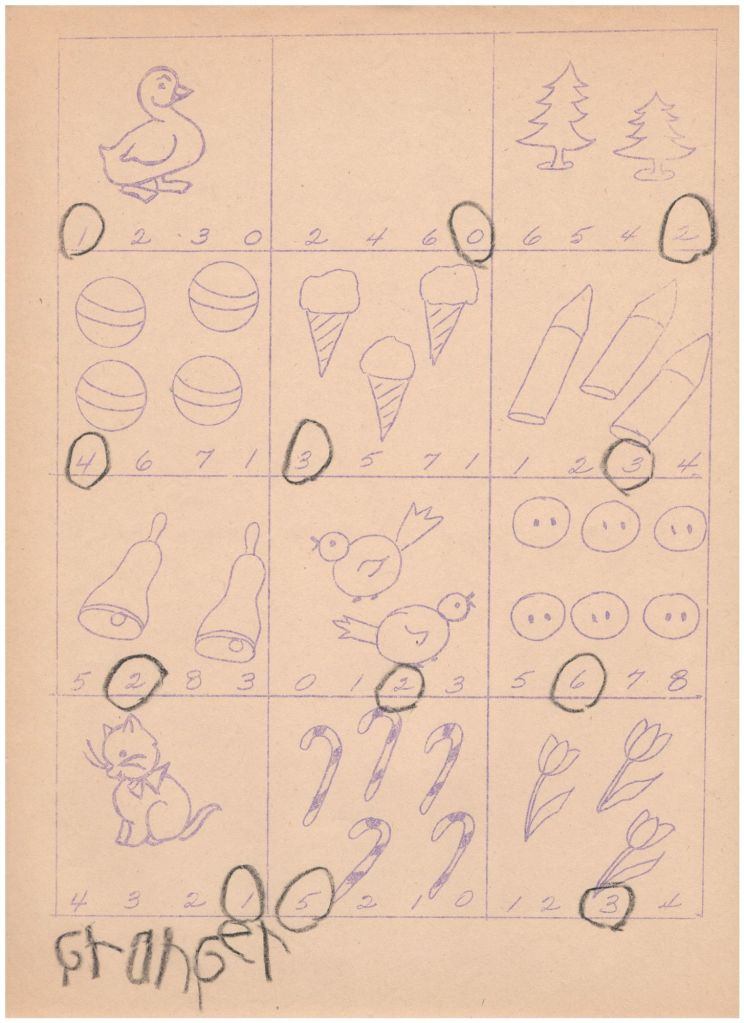

My parents saved a few of my kindergarten papers, including one where I used a black crayon to identify how many objects I saw.

My earliest memory of school math was learning about sets in first grade, drawing big circles around things. That was a consequence of the “New Math” that was a dramatic but temporary change in how math was taught in American grade schools after the Sputnik crisis.

I also recall addition and subtraction in a consumable workbook with an addition problem on a page with a subtraction problem on the facing page. I immediately noticed that the answer to the addition problem was the same as the answer to the accompanying subtraction problem, over and over. I figured it had to be a sneaky trick: they were trying to lure me into complacency, skipping doing the subtraction problem and just writing in the answer. I figured at some point the pattern would break.

I wasn’t about to fall for that, so I diligently did every subtraction problem. The pattern never broke, all the way to the end. I remember turning the last page and heaving a big sigh. All that wasted mental effort!

Flashback to flash cards

In second or third grade, my mother said I had to learn the multiplication tables. She bought a set of flash cards, and I remember stretching out on the smelly green shag carpet in the hallway outside my bedroom. My mother sat cross-legged, flash cards in hand, and proceeded to torture teach me.

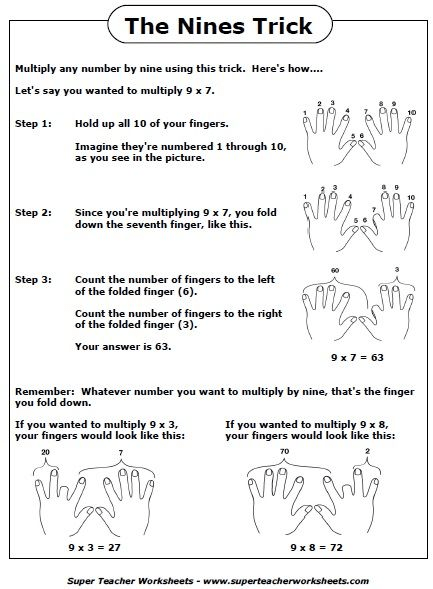

Oh, how I hated it! The only thing I liked was realizing that the sum of the digits in the answers to all of the nines added to nine. 9×3=27 and 2+7=9, 9×6=54 and 5+4=9, and so forth.

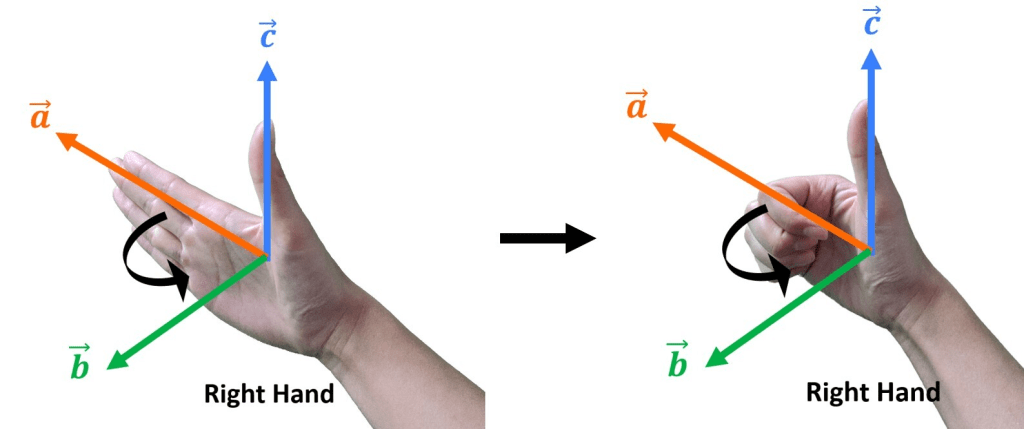

I intuitively realized that had something to do with nine being the final of the Arabic numerals and carrying, but I just used the factoid as a double-check, rather than adapting it into a hand trick. The only hand tricks I ever learned for math were for vector cross products.

Discounts

Difficulty with math was what led me to try and cheat for the only time in school. Mrs. Zaffos was my math teacher in sixth grade, and she could be demanding. I remember her ruler coming out if you said, “one hundred and four” rather than the correct “one hundred four” when you meant 104.

When she taught us discounts, I couldn’t grasp it, and I was too intimidated to ask for help. So the night before the quiz, I took my white vest and used a ballpoint pen to write each discount problem along the inside. My scheme was to learn forward during the test and gaze down inside my vest.

When Mrs. Zaffos started passing out the papers, I felt terribly guilty about my impending behavior and began to sweat profusely. She reached me and exclaimed, “What is wrong with your shirt?”

I looked down to see blue ink stains spreading across my sweaty shirt. I looked up and confessed, “I’m cheating. The answers are written in my vest.”

Mrs. Zaffos pulled open one panel of my vest, revealing an illegible blue stain. She grinned and said, “I don’t think you’re much of a cheater, Granger. Do your best, and I’ll help you later.”

I don’t remember the grade I received on that quiz, but I do recall Olga Lorraine Zaffos giving me extra help until I figured out discounts, God bless her. I was never tempted to cheat in school again.

Regular math was not for me

Our family moved as I finished elementary school, and although we were in the same school district, I was shifted to a different junior high than everyone I had known since first grade. For whatever reason, my records didn’t transfer properly, and my parents had never even heard of Honors classes. So while I got to pick a couple of electives, including Photography, I was enrolled in the regular track for all of the required subjects.

After a week at my new school, my mother asked me how it was going. I said everyone was nice enough, but they seemed rather slow. Even junior high math had been incredibly easy…so easy that it was quite dull.

A week later, the school called my mother. They had finally received my records, and I was to be immediately shifted to Honors English, Honors Science, and Honors Math. I was nonplussed, not realizing that there were classes of differing difficulties. I showed up in the new classes, where I was told that none of my grades from the regular classes would come over, and I needed to quickly make up a couple of weeks of work. I wasn’t at all worried about English or science, but could I handle Honors Math?

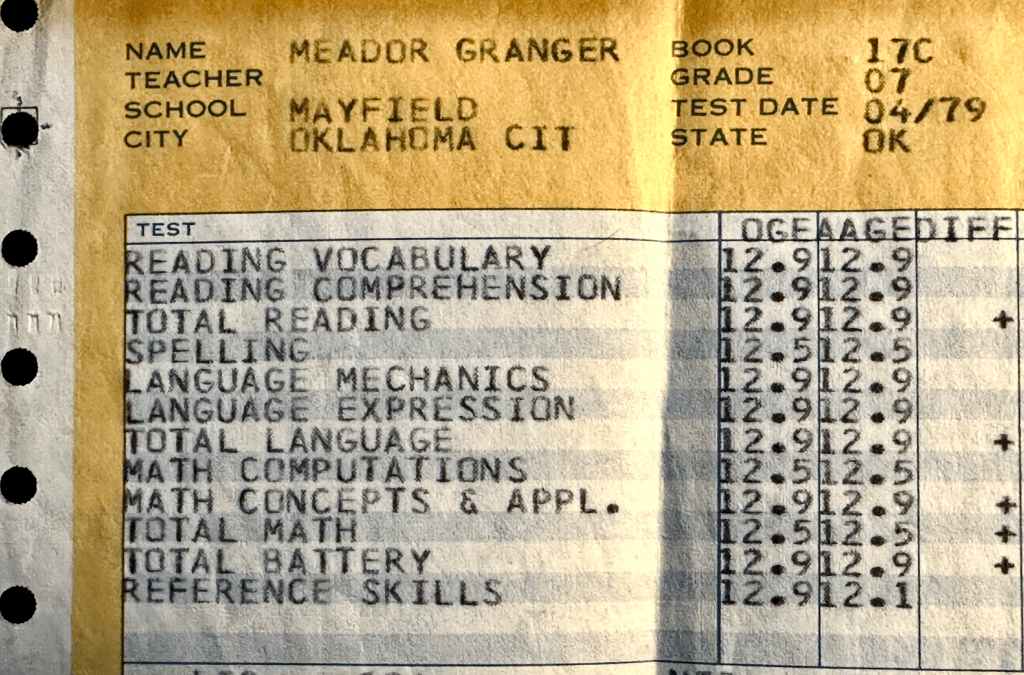

The answer was yes, and it was my seventh grade science class that motivated me to value mathematics. It used the old Introductory Physical Science curriculum developed in the 1960s by the Sputnik-era Physical Science Study Committee. That featured lots of hands-on laboratory work, including us constructing wet cells to power some basic electrical circuits. I decided to read about physics.

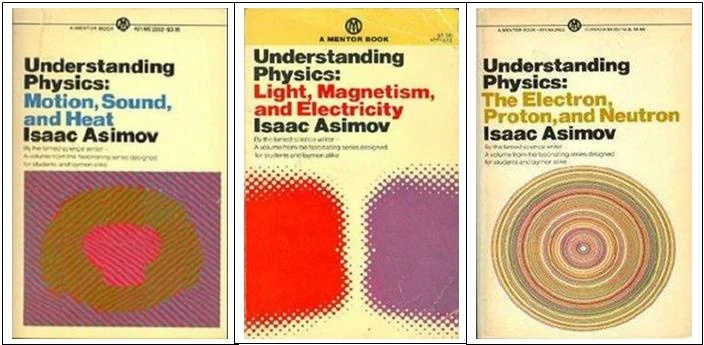

Since I had enjoyed his science fiction novels, I bought and devoured Isaac Asimov’s Understanding Physics books. They were conversational, but chock-full of equations.

The bus would drop me off at school each morning, long before they lifted the metal gates that sealed off the classroom wing. I would traipse over to the choir room, climb the risers, plop down in a seat, and read about physics. I remember how a bored eighth grader one morning spotted me up there reading and came bounding up.

“You’re always reading. What’s so interesting, sevvie?”

At the time, I was a 4’8″ prepubescent seventh grader who weighed 72 pounds. I was known as the worst performer in Physical Education class, except on rules tests, until an even smaller and scrawnier Vietnamese refugee enrolled. So I was quite intimidated by this big eighth grader. I nervously showed him the cover of the book, and his face broke into a wide grin. “Physics?!? Wow! That’s a deep subject for a little guy like you! You must be pretty smart!”

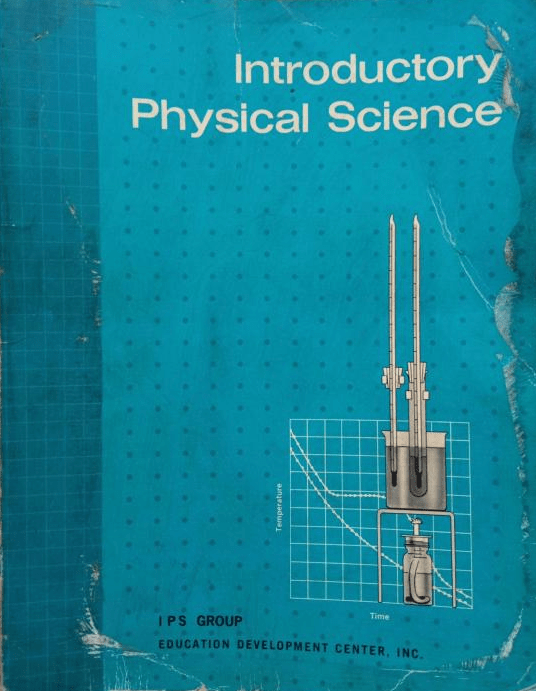

Well, yeah, I was an outlier on one end in PE and on the other end in academics. In April, we all had to take the California Achievement Test. My Obtained Grade Equivalencies were all grade 12…even in math.

A concrete thinker in Algebra

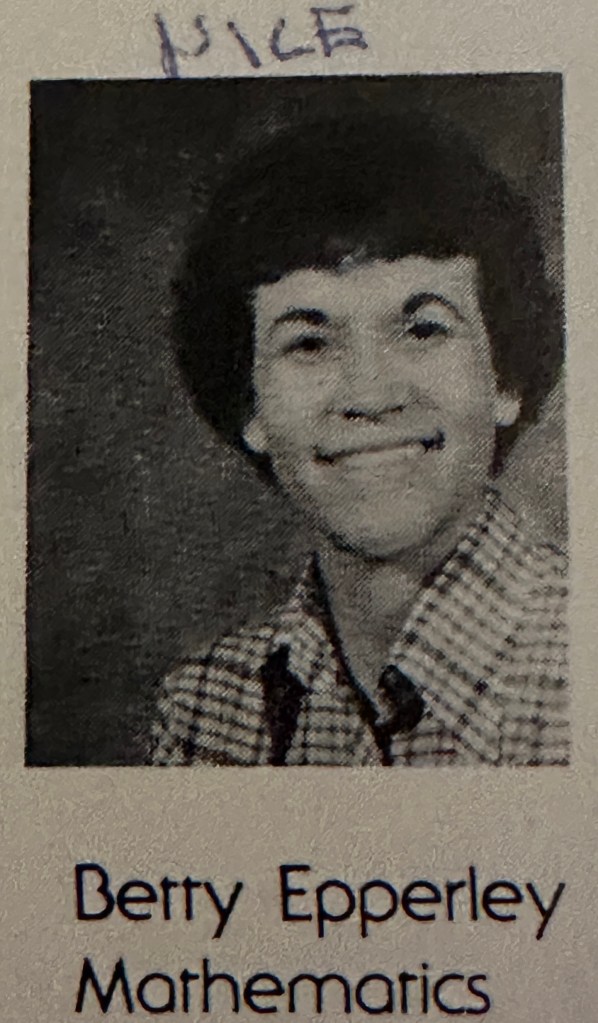

That didn’t make my introduction to algebra the next year any easier. I had to work hard to earn an A, despite the able efforts of my kind teacher, Betty Epperley.

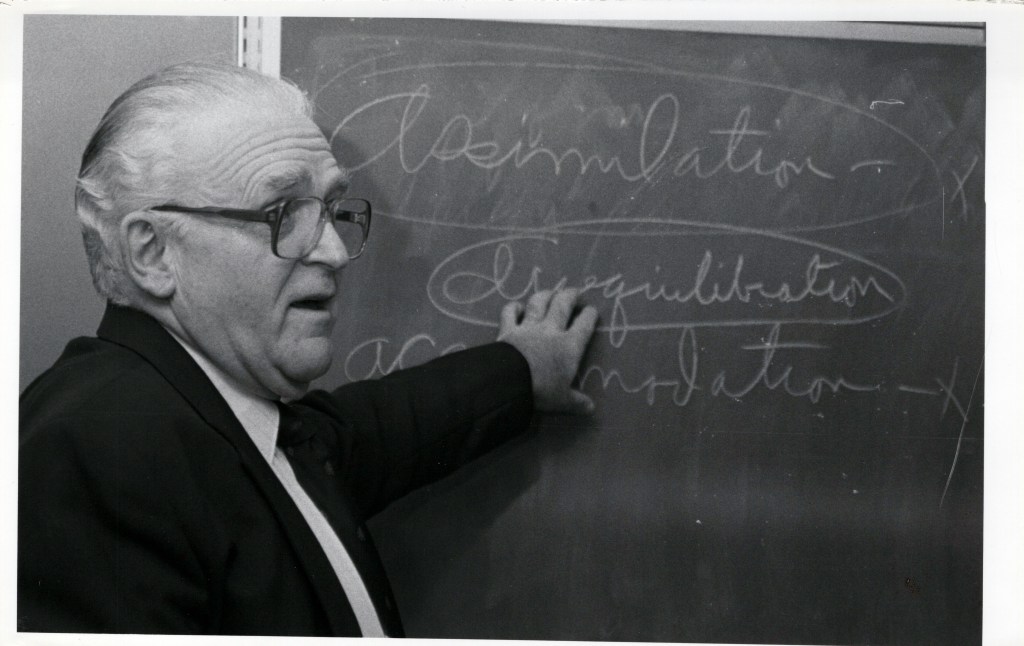

I remember spending hours on the phone some nights with classmate Susan Plant, helping each other through the homework. Once I was trained in Piagetian learning theory in college, I realized that Susan and I were still concrete operational at the start of eighth grade; our minds had not yet matured enough to handle formal operations. Thankfully it began to click mid-way through. As we became formal operational, abstract algebra finally began to make sense.

Mrs. Epperley had to be out for some weeks, and we had Ms. Moon, a long-term substitute. She had a British accent, and I was taken by how she wrote her sevens with a strike-through. I adopted the habit to ensure my sevens and ones were distinct. That habit has persisted for 44 years.

What did the little acorn say when he grew up?

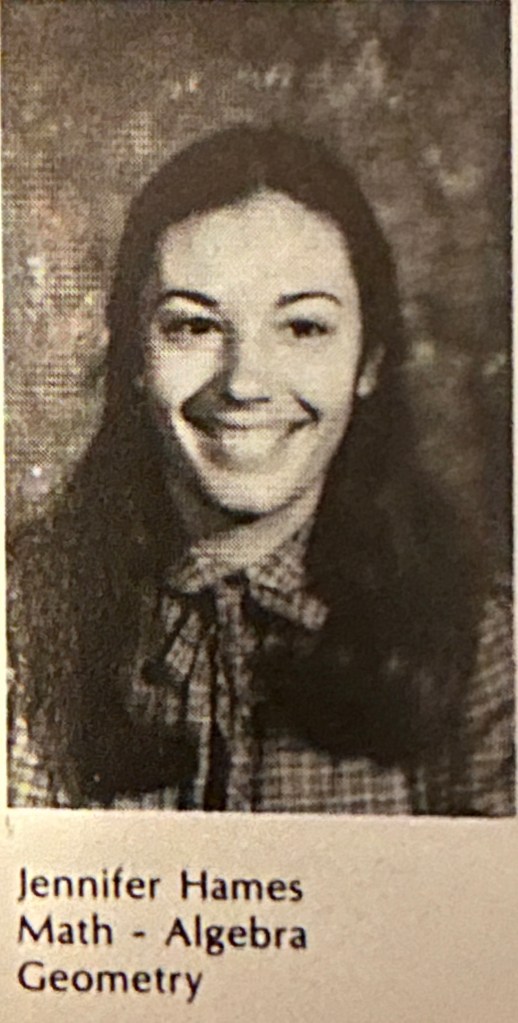

I took Honors Geometry in ninth grade with Mrs. Hames, and I was smitten.

Geometry was so elegant and sensible, and I could visualize everything. I actually enjoyed constructing mathematical proofs and ending them with quod erat demonstrandum, while many of my classmates groaned about the subject.

Speaking of groans, the answer to the above question is, “Gee, I’m a tree!” I have a whole series of geometry jokes, but I’ll spare you more misery.

Algebra II and Math Analysis

In grade school, when asked what I wanted to be, I had always responded, “Music teacher.” However, my father always wanted me to become a writer, and he paid for a writing tutor one summer and ensured that I had my own Science Research Associates Laboratory writing kit at home. When I was enrolling in high school, which was grades 10-12 at the time, Honors and later AP English were inevitable, but I had more freedom in choosing courses than in junior high. I asked my mother for advice on what electives to take. She responded, “You like science and you are actually good at math. So take all the science and math courses you can.”

Beth Thompson was a pale and precise woman who trained her Honors Algebra II students to fold our quiz papers in half length-wise after completing them, writing our name and period on the top of the folded paper. That left a tempting blank space below, and I always finished early. So rather than turn in my paper, I would write a trivia question on it.

Mrs. Thompson would gamely try to answer my questions when she graded my quizzes. I remember stumping her with, “What is a hemidemisemiquaver?

Jay Reagan was the baseball coach and Honors Math Analysis teacher. I enjoyed his class a lot, and throughout my life when people diss coaches with the stereotype that they can’t teach, I always point out that one of my best math teachers was a coach. Baseball, of course, is a sport drowning in statistics, and Coach Reagan could hold his own.

At the end of the academic year, we had actually made it through most of the textbook, a rare feat, and he had us do a fun unit on construction. Geometric construction, that is, with a straight edge, compass, and other devices. I ate that up, and years later, when I taught my own students about Kepler’s First Law of orbits, I made sure to show how an ellipse can be formed by taping the ends of a piece of string at the foci, pulling the string taught with a marker, and moving the marker while keeping the string taut to form an ellipse. That was a valuable way of making the foci more relevant to students, and the object being orbited is always located at one focus of the elliptical orbit.

Mu Alpha Theta

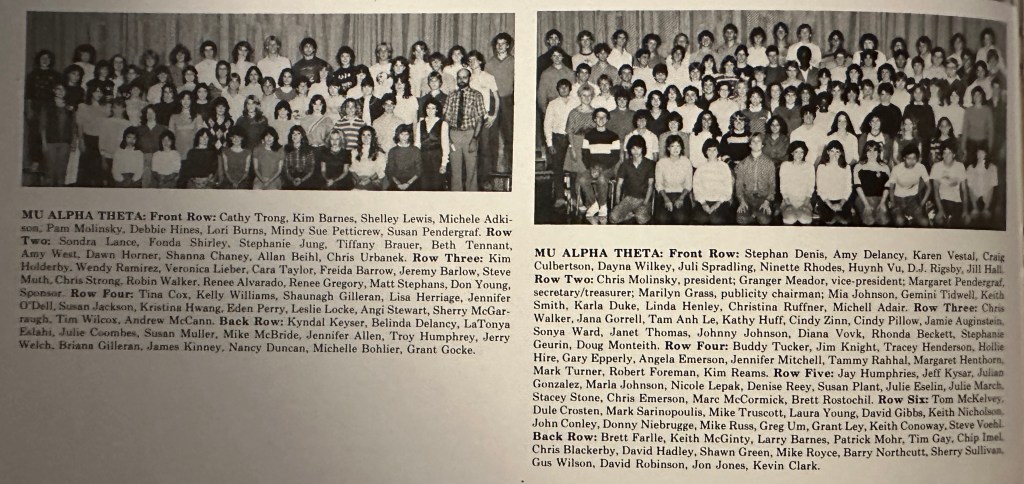

In 10th grade, I had been elected homeroom representative for our Honors Algebra II class in the Student Council, but I didn’t start actively running for offices in student organizations until I went steady with a girl starting in 11th grade. She was more extroverted and motivated me to become the Vice-President of the Honor Society, Parliamentarian of the Junior Classical League, Secretary of the Science Club, and, of all things, Vice-President of the rather large Mu Alpha Theta club…Mu Alpha Theta…MATH.

Our club initiation was at a buffet restaurant, something I had not experienced. The lighting was dim, and I remember going down the buffet line and what I thought was a big pan of mashed potatoes. I scooped a big glob out onto my plate. When we sat down to eat, my girlfriend eyed my plate and asked, “Why did you get so much butter?” Oops!

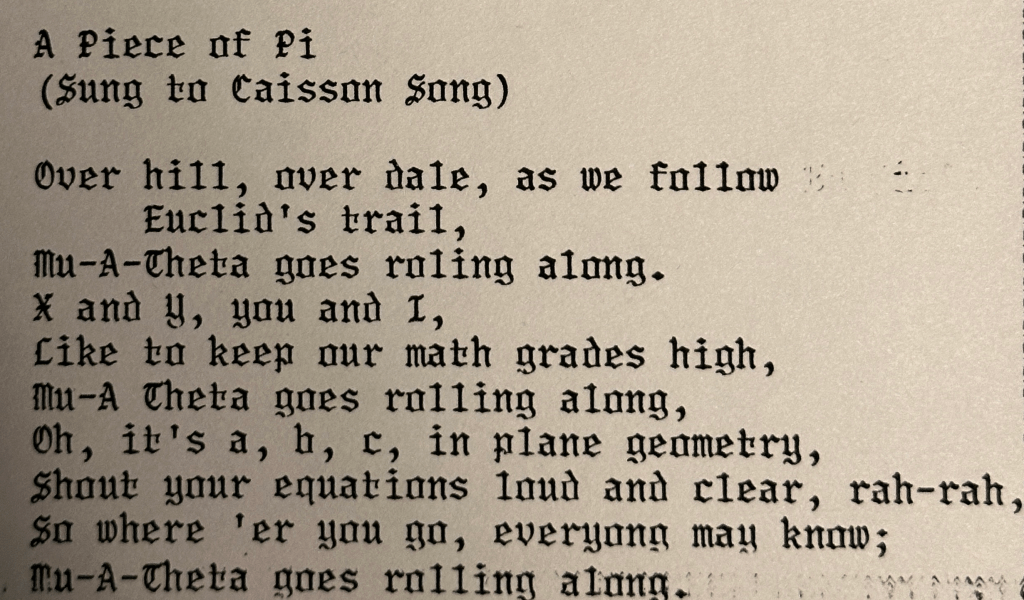

We sang a hokey song at our initiation which was a parody of the original Caisson song once sung by the U.S. Army. Here it is, as printed in the initiation program, complete with typographical errors:

Our club’s fundraiser was Cosino Casino, where people bought tickets in the school cafeteria one evening to use in playing games of chance. We included math lessons with each game, and my girlfriend and I were charged with running a roulette table. We bought a cheap lazy Susan turntable at the T.G.&Y. and my girlfriend decorated it and ran the table.

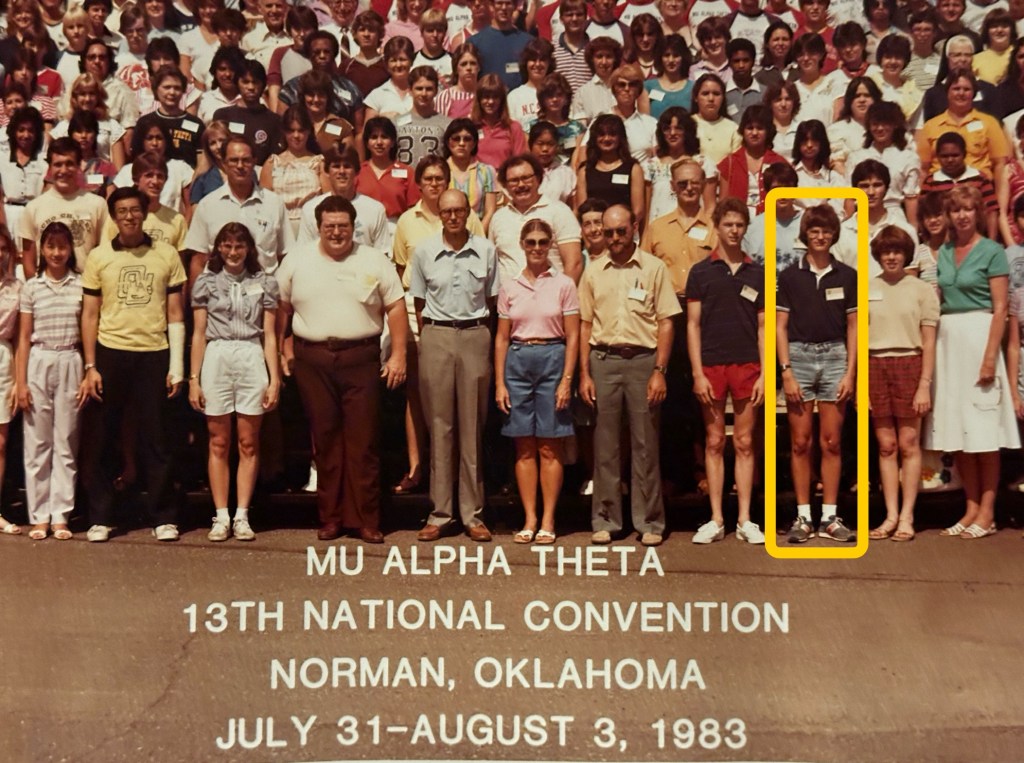

Our school co-hosted with Norman High the national Mu Alpha Theta convention in the summer of 1983. Hundreds of kids from all over the country converged at the University of Oklahoma for activities, including plenty of math contests. I remember staying in one of the high-rise dorms. I would end up spending my freshman year in college living in one of them.

After graduating from high school, I attended the 1984 national convention in New Orleans. We went to the World’s Fair, where I remember seeing the space shuttle Enterprise and visiting Sea World. My other memory is of dining at a restaurant in the French Quarter and ordering a steak. When they asked how I wanted it, I didn’t know what they meant. The waitress prompted me, “Rare? Medium? Well done?”

I figured “well done” sounded good. When my steak came out, it was blackened, but not in the Cajun fashion. Someone across from me noticed it and asked me how I’d ordered my steak. The math teacher seated next to me looked over and responded, “Cremated.”

Math Bowl & the ASVAB

In addition to Mu Alpha Theta, I was on our high school’s Math Bowl team. Great…a math competition with top students from other schools, all with time pressure! I was actually surprised at how well I performed, having been cajoled into joining and figuring I might be a huge flop.

I did well enough on the PSAT and SAT to earn a College-Board-sponsored National Merit Scholarship, and I took the ASVAB, the Armed Services Vocational Aptitude Battery. Part of the results identified recommended roles we might fill in the military. The chief recommendation it gave for me was Nuclear submarine engineer.

Calculus

I took Calculus in high school from Judy Jolliff; she is in a pink shirt three down from me in the above convention photo. She was spirited, but I found Calculus quite difficult. I remember our class sometimes looking to Barry Northcutt, the school quarterback, for help, as he was a Calculus whiz. Yet another stereotype smasher.

For both semesters of Calculus, although I was exempt from mandatory finals thanks to my attendance, I had to take those tests and score well, including acing the second one, to earn an A in the course. I studied hard and pulled it off.

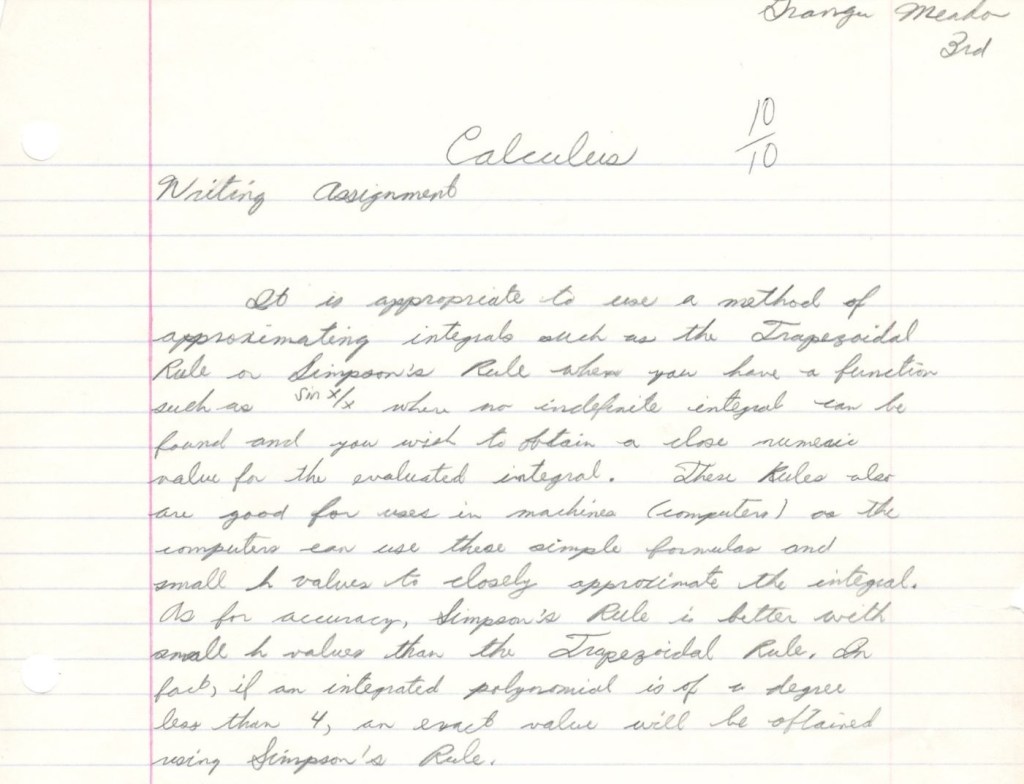

It is telling that the only high school Calculus paper I saved was one in which I was writing, not calculating.

My top student awards in upper school were in English for three out of four years, Biology, Physiology, and Physics. I won state scholastic meets in Spelling and English, and my writing earned me some awards and was instrumental in my being named a U.S. Presidential Scholar by President Reagan, which took me, my parents, and a favorite teacher to the White House and a week in Washington, DC. The only time I was the top math student was in Honors Geometry, but I wanted to learn more physics in college, despite my ambivalence about pure mathematics.

When I enrolled at university, I avoided pursuing a Physics major, given its theoretical emphasis and demanding mathematics. Instead, I tried Engineering Physics, which was more practical-minded. My ACT English scores were so high that the University of Oklahoma (OU) gave me free advanced standing credits in English, but I had to take tests at the university to earn advanced standing credits in math. (The only Advanced Placement course at my high school was in English, and while I was the top student in the course, I didn’t take the AP test for college credit since OU had already awarded me credits.)

I managed to test out of Analytic Geometry and Calculus I. I decided to not even try to test out of Calc II, as I thought it would help me to repeat it, bolstering my grasp of Calculus to help me in my physics classes.

Well, Calculus II wasn’t as hard as I had imagined; my high school course had actually prepared me well. But Calculus III would be entirely new topics, and I wanted to avoid a big lecture hall class like I had for Calculus II. So I enrolled in a night class, which I knew would be small with some adult students. At the time, the university ensured the professors for the night math courses were native English speakers to avoid getting complaints from adult students who didn’t tolerate accents well.

That gambit paid off, and it was the first time I enjoyed Calculus, as the topics included things like parametric surfaces where my love for geometry could shine.

Differential equations with Resco

I went on to courses in ordinary and partial differential equations, which the university called Engineering Math I and II. The first course was in a huge lecture hall with Dr. Richard Resco. Right from the start, we knew it was going to be interesting.

He would always come into the hall, no matter the weather, in shorts and sandals. On the first day, he gazed out at the hundreds of engineering students and told us that he wanted us to appreciate math for its own sake, not just as a tool.

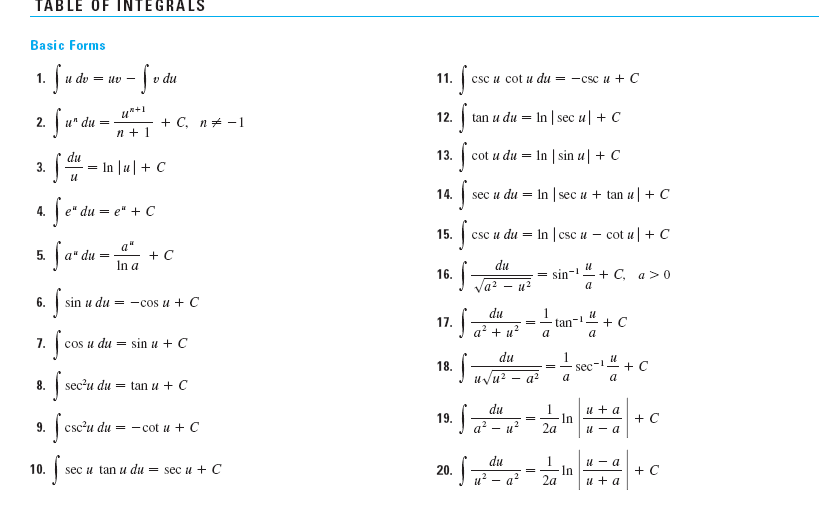

My girlfriend and I were seated in the front row. Resco walked up to her, flipped open her textbook, and loudly asked, “What are those things printed inside the cover?”

She replied, “Integral tables?”

Dr. Resco nodded, and then slammed the book shut. “They’re a crutch, not a wheelchair!”

My girlfriend looked over at me, wide-eyed, and then glanced down at my notes. I had written, “Integral tables: crutch not wheelchair.” She rolled her eyes and sighed.

Another memorable incident is one I often shared with my own students when we were studying friction and they learned that we symbolize the friction coefficient with the Greek letter mu (μ). One day, Dr. Resco had worked his way through some calculations that took a couple of pages just for one problem. Then he showed us a shortcut, involving the integrating factor, also labelled μ, which drastically shortened the process.

After demonstrating how μ worked, he turned around, triumphant. Then his face fell as he gazed around the hall. He grew visibly frustrated and yelled, “You just don’t get it, do you?”

My girlfriend and I, who no longer sat on the front row, glanced at each other. Dr. Resco threw down his chalk and started gesturing at the boards of calculations.

“Mu is a gift! You engineers have no appreciation for it?!? Mu is your friend!”

Then he went down on his knees and started genuflecting to the board. “You should appreciate mu! Worship mu!”

My girlfriend again glanced over at my notebook. I had written, “μ is our friend, and Resco completely lost it today.” She nodded in agreement.

Later I found out from my friend Sam, who was a math major with Dr. Resco as an advisor, that Resco had been going through a bad divorce at the time. Bless his heart. Richard Resco taught at OU from 1981 until his death from cancer in 1997. He bequeathed his entire estate of almost $350,000 to endow Graduate Fellowships in Mathematics at OU. And I still remember that mu is my friend.

The Walter Way

My final undergraduate math course was a stark contrast to its predecessor. Engineering Math II, which was about partial differential equations, was taught in a small classroom with Dr. Walter Wei. I guess most engineers didn’t need to go that far in math, but Engineering Physics demanded it.

Wei was new to teaching and unfamiliar with class procedures. While he was friendly, I sometimes struggled to understand his heavily accented English, and I remember being utterly stumped by one assignment. When I showed up for class, defeated, I was relieved to find that no one had been able to do it. Dr. Wei came in, and we shared how all of us were baffled. He grinned, admitting that there was no known solution to the problem he had posed. He had wondered if one of us might find one!

Someone once asked about his research, which I think had to do with topology or manifolds. He said he was working on developing a new mathematical technique, laughingly saying that he hoped it might become known as “The Walter Way”.

We did have revenge on Dr. Wei, telling him that it was a tradition for the professor to bring the students milk and cookies for the final exam. He did so, and when we sheepishly confessed that we had been pranking him, he looked at us, goggle-eyed, and then laughed heartily. And yes, I enjoyed having milk and cookies on the last day I took a math class as an undergraduate.

Changing majors

The termination of my undergraduate math courses coincided with a change in my major. While I had loved my first courses in Physics for Majors, with the fabulous Dr. Stewart Ryan, aka Dr. Indestructo, and Modern Physics with Dr. Suzanne Willis, I didn’t appreciate the subsequent engineering and physics coursework. Immediately after being named an Outstanding Sophomore in Engineering Physics, I decided to quit.

I remember standing in my apartment in Norman, wracking my brain about what major to shift to. A favorite university professor of mine had tried to recruit me into Letters after having me in Latin class and her honors seminars on ancient Greece and Rome. But I had demurred. Should I switch to Letters? That might lead to teaching those subjects at a university. However, I liked high school far more than university, where many professors cared more about their research than about teaching undergraduates. What to do?

I had once wanted to teach music. I liked high school. I loved basic physics, but I was disillusioned with college and engineering. So what had I liked enough to want to do it for a living?

Teaching…high school…physics. Suddenly, I felt a surge of elation, a true calling I had lacked until then. A fresh course of action coalesced.

If you’re searching for that one person who will change your life, take a look in the mirror.

I applied to the College of Education at OU, determined to become a high school physics teacher. Dr. John “Jack” Renner, an outstanding leader in science education and the Learning Cycle, interviewed me. I thought he would be thrilled to have me, but after reviewing my transcript he tried to send me away.

Jack Renner said I was too bright to be teaching high school science, that full-time physics positions in Oklahoma high schools were quite rare, and that I should stick with Engineering Physics. “Get your degree and then teach physics at a university, not a high school.”

As you might guess, I was adamant. He eventually caved, and I informed Dr. Ryan, my Engineering Physics advisor, of my decision. He was disappointed but kind and understanding.

No minor matter

Back in 1988, to be certified to teach a high school subject, you had to have earned a certain number of college credits in it and also pass a certification test. I was told that if I wanted to teach physics, I should also certify in math since full-time physics positions were rare, and they often took on some math courses to fill out their schedule.

Well, I wasn’t about to do that. I did ask if I had enough math credits to earn a minor in Mathematics. They checked and said that if I would take just one more math course, such as a methods course about teaching it, I would indeed earn a minor. Another math course? No thanks!

So instead, along with Physics, I certified in Chemistry, Biology, Botany, Zoology, and Earth Science. If I had to teach something else, it would be a science course.

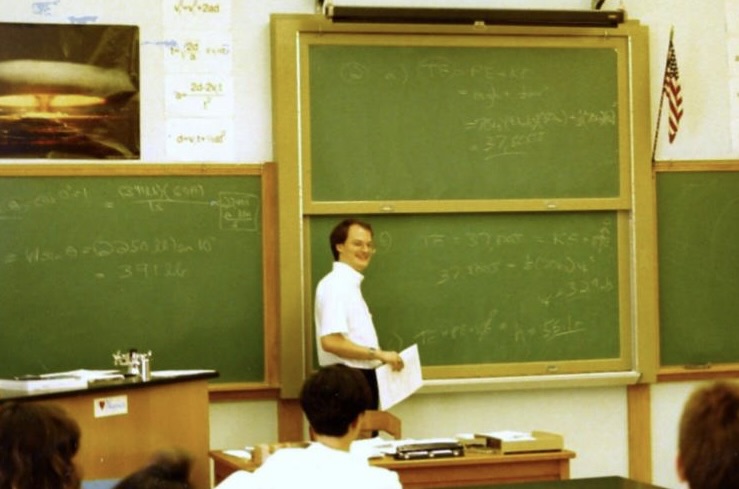

My change in major after two years of Engineering Physics coursework delayed my graduation by a semester, even with me taking summer school courses. So I graduated in December 1988 and substituted in the three high schools in my old Putnam City district from January to May 1989. Substituting when I was 22 years old was challenging, but a happy memory is when I filled in for one of the Calculus teachers, who also had a couple of physics sections. The teacher had left instructions for the students to read the next section in the respective textbooks and do the best they could on the assignments.

As the first class of students walked in for Calculus, they saw me and clearly thought, “No lesson today!”

So they were shocked when I told them to get out their notes and proceeded to teach that day’s lesson. Some gasped, “You’re a sub who can teach calculus?”

When I finished the lesson, the kids actually applauded and got to work on the homework problems, with me circulating to help them individually as needed. Word spread, and for the rest of the day kids came in, saying things like, “I heard we have an amazing sub today.”

My reputation was sealed at that school when I taught the physics lesson as well. That experience was so redeeming, after my years of struggling with math, that I almost regretted not certifying to teach math. Almost.

Wonderful write up of your education history! My boys were very lucky to have you as a teacher!

My best to you and the boys!