What do the song PEnnsylvania 6-5000, the book BUtterfield 8, and the movie Dial M for Murder have in common? All of their titles refer to telephone exchanges. Bartlesville only used exchange names in its phone numbers for about a decade, circa 1958 to 1968.

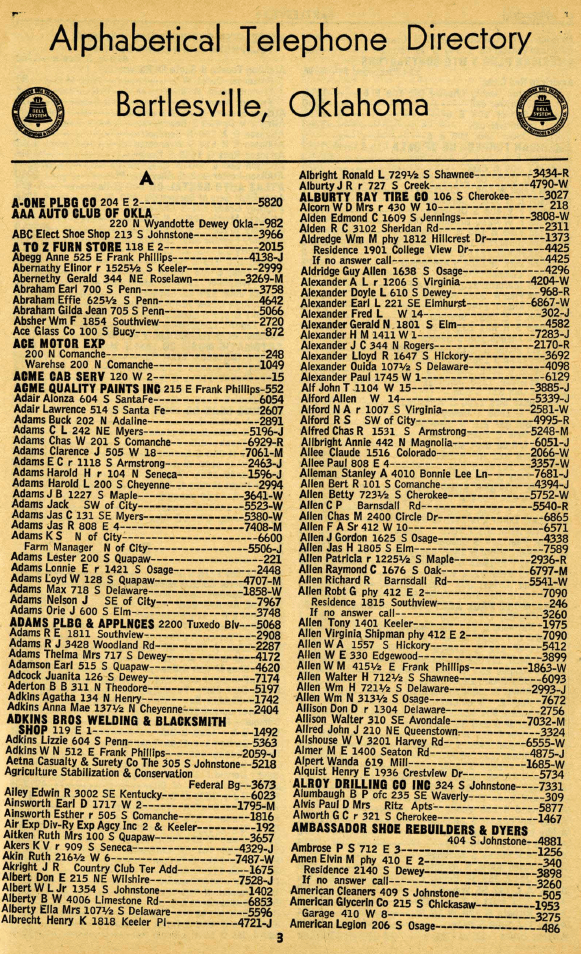

In the early days, there were so few telephone lines in smaller communities that phone numbers were just a few digits. The 1907-1908 Prewitt’s Directory for Bartlesville, Indian Territory, which was printed just before statehood, has phone numbers of two and three digits.

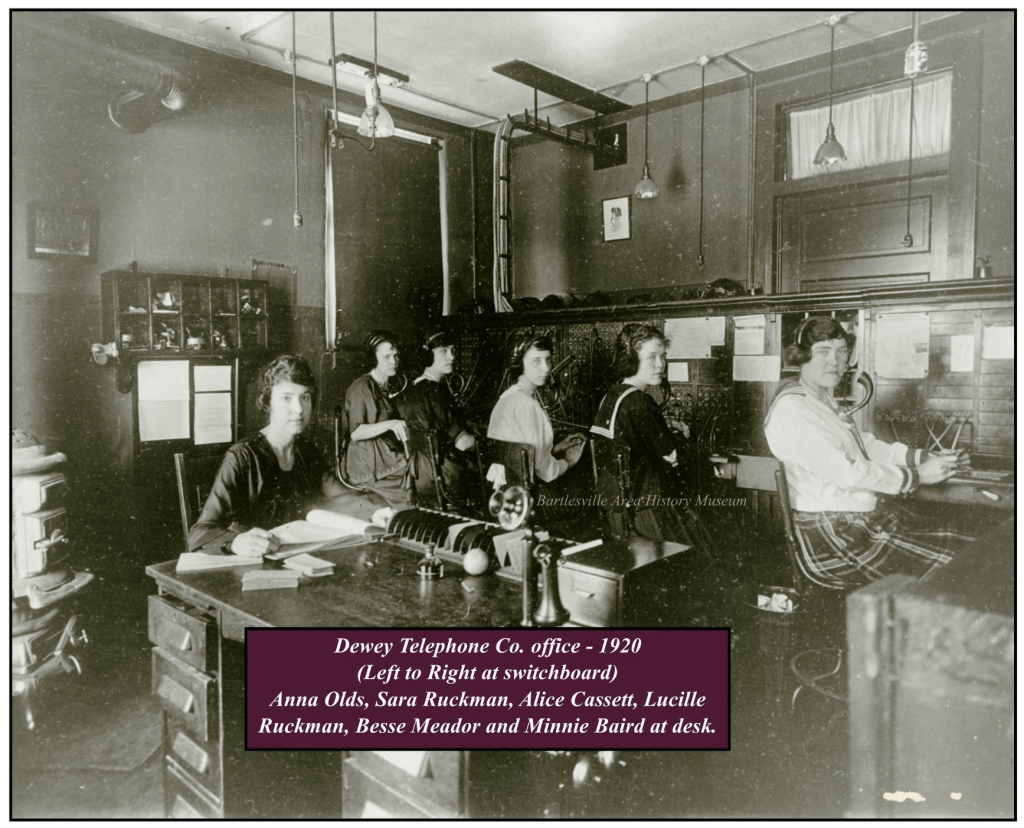

Telephone service in Bartlesville dated back to the late 1800s with an exchange above the Hull Drug Store on the south side of 3rd Street (now Frank Phillips Boulevard) between Johnstone and Dewey Avenues. It opened with three phones, which expanded to seven, and the bell was hooked to the bed of the operator. The first telephone operator was a Ms. Green, and many of the early phones were for doctors.

The Cherokee National Telephone Company established a Bartlesville exchange in 1901. In 1905 the Indian Territory Telephone Company had a copper line stretching from Bartlesville to Tulsa, and that same year the Cherokee National was purchased by Pioneer Telephone and Telegraph.

As communities grew, phone numbers grew in length to where they would challenge the 4-9 digit short-term memory of a typical human being. So Bell Telephone started using telephone exchange names in locations needing over four digits. Those were memorable names assigned to a central office’s switching system. Usually the first two letters of the name corresponded to prefix digits in a two letters+five numbers format, although various combinations and lengths were in use in different communities.

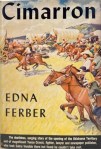

BUtterfield-8 was a 1935 John O’Hara novel, and then a 1960 movie, in which BU-8, or 288, was the exchange for Manhattan’s well-to-do Upper East Side.

PEnnsylvania 6-5000 indicated 736-5000, which was the phone number for the Hotel Pennsylvania in New York City. Its phone number became the title of a swing jazz and pop standard of the Glenn Miller Orchestra.

As for Dial M for Murder, that was a 1954 Hitchcock film based on a stage play in which a scheming husband dials his home phone MAIda Vale 3499, or 624-3499, to awaken his wife and set in motion an attempted murder.

The rotary dial for a telephone was patented in 1892, with holes in the finger wheel introduced in 1904, but they weren’t common until the 1920s.

Area Codes

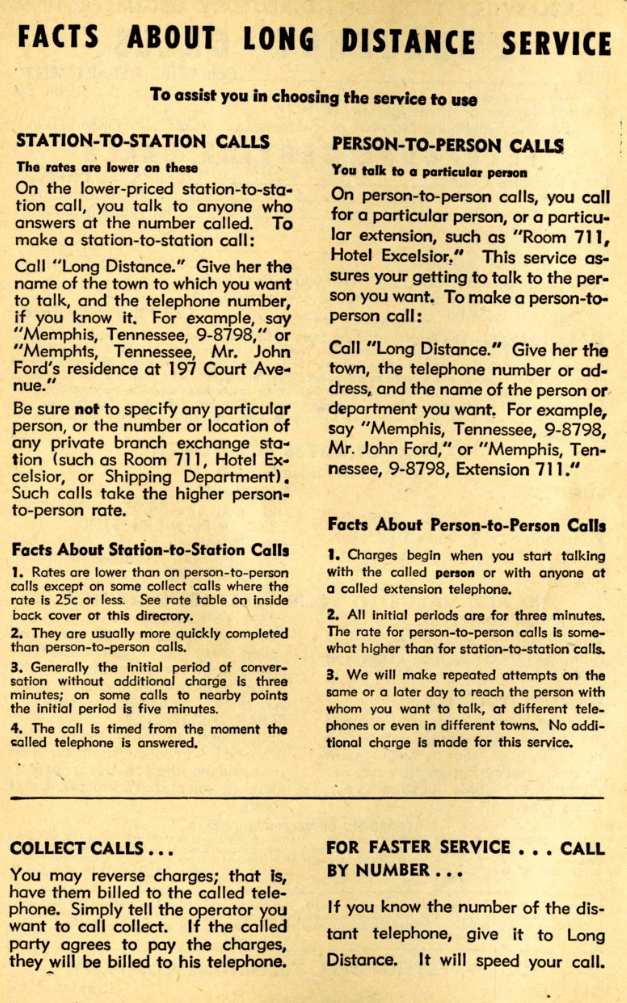

The popular culture references I cited all lacked something: an area code. That’s because at the time you didn’t need to dial an area code as part of a local phone number. In fact, Direct Distance Dialing, allowing one to make long-distance calls without the assistance of a human operator, didn’t begin until 1951, slowly expanding from New Jersey to become widespread in the 1960s as the system began to include automatic toll-switching centers, electronic switching systems, and automatic message accounting computers.

I’ve shown a page from the 1955 Bartlesville telephone directory with instructions on how to make a long distance call. You can tell they didn’t have Direct Distance Dialing yet!

The 405 area code had been established by AT&T and the Bell System in 1947 and covered the entire state of Oklahoma at that time. In 1953, the 918 code for northeastern Oklahoma was split off from 405. 580 for western and southern Oklahoma was split from 405 in 1997.

Until 2011, 7-digit local dialing was still possible statewide, but then 539 was added as an overlay to the 918 area code rather than doing a split. Having two area codes for the same geographic region forced a change to 10-digit dialing there, and that spread to the 405 area code region in 2021 when 572 was added as an overlay to it.

Pioneer Telephone

Oklahoma had 135 commercial systems and 63 incorporated phone companies at statehood in 1907. By 1912, Pioneer Telephone and Telegraph Company had 115 exchanges in Oklahoma, with 114,975 miles of aerial wire and 19,480 miles of underground wire.

The Pioneer Telephone Building still stands in downtown Bartlesville on the west side of Dewey Avenue north of 4th Street, with its distinctive blue bells on the pilasters. It was an early fireproof building in the city, erected just a couple of years before Southwestern Bell was formed in 1912 as a consolidation of the Southwestern Telephone Company of Texas, Louisiana, and Arkansas with the Pioneer Telephone and Telegraph Company, the Missouri and Kansas Telephone Company, and the Bell Telephone Company of Missouri.

A few miles north was the small telephone office in Dewey. At one time, calling from Bartlesville to Dewey was a long distance call, something we struggle to imagine these days.

Contrast that to the Bartlesville phone office in 1929, with over three times as many operators for local, toll inward, and outward stations.

Back in 1954, Southwestern Bell had an open house at its Bartlesville office, inviting residents to come see the equipment in action, see a machine that “plays tick-tack-toe and never loses a game”, and see a demonstration microwave relay in which they could break the beam transmitting music with their hand and reflect it with a metal mirror.

I used to do a related demonstration when I taught Advanced Placement physics night lectures at Bartlesville High School. Instead of using a microwave transmitter and receiver, I would modulate a laser beam with the audio signal from my iPod or iPhone and aim it at a solar panel connected to an amplified speaker.

Before FEderal-6 and EDison-3

Back in the mid-1950s, Bartlesville did not yet use exchange names in its phone numbers, but it did have some numbers with party line suffixes. The 1955 city telephone directory is filled not only with three and four-digit numbers, but also four-digit numbers followed by the letter suffixes J, M, R, or W. Those indicate party lines, where multiple households shared a number. The suffix letters they used had been chosen to not be easily misheard when spoken.

[Source]

Some dials back in the day lacked most of the letters, but still sported the letters needed to help you complete a party line call.

The concept of the party line was instrumental to the plot of another popular entertainment, the 1959 movie Pillow Talk, with Doris Day and Rock Hudson unhappily sharing a line.

Other phone number schemes were also in use. The same 1955 phone directory has two-digit numbers in Copan mixed in with longer sequences like 814-F-11 and 810-F-31.

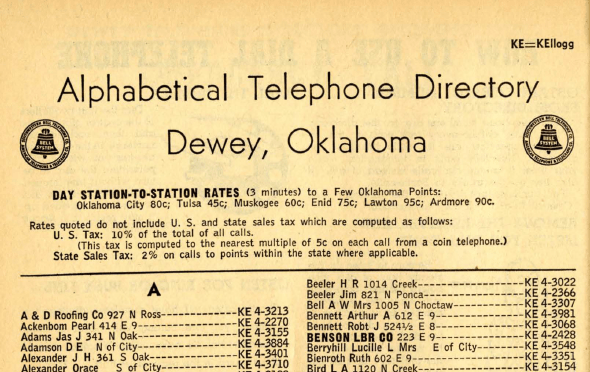

Dewey phone numbers in 1955 did use the exchange name system. They were all KE 4-#### or KEllogg-4 numbers.

A new building briefly brought FEderal-6 and EDison-3 to town

In 1957, Southwestern Bell constructed a $3 million Bartlesville office on the southwest corner of Dewey Avenue and 6th Street (now Silas Street). It was two stories with a basement, built such that a third floor could be added.

The ground floor had the big crossbar switching system and customer service, while upstairs was the microwave system and mobile phone equipment and operators. The basement had the test room, which could be used to determine if someone added an extra line without paying for it.

That new facility also brought the use of seven-digit numbers with exchange names. Bartlesville started having FEderal-6 numbers associated with the west side of the Caney River and EDison-3 numbers on the rapidly expanding east side.

Witness the mix of FEderal, EDison, and Dewey KEllogg exchanges in a yellow pages listing for Cities Service gas stations in 1959.

The use of phone exchange names in phone listings began to be phased out in the 1960s, so FEderal and EDison didn’t last very long in Bartlesville. I was assigned a 335-#### phone number when I moved to town in 1989, so I suppose I could have shared it as EDison5-####, but that would have elicited some stares and confusion.

Back then, the Bell Building next to the old Civic Center was still adorned with a large microwave antenna up top, hidden within a decorative shroud. That provided a wireless link to Tulsa, via a large relay antenna near Ramona, in case the regular lines were cut.

By 1968, 40% of all long-distance telephone traffic in the USA was carried by AT&T’s TD-2 microwave relay network, and it also carried 95% of the country’s inter-city television signals. The development of fiber optic cables and geostationary communications satellites eventually rendered the microwave relays obsolete, and in 1999 AT&T sold off the towers.

They removed the KKB56 microwave antenna from atop our local phone building some years ago, and nowadays far fewer employees work in the building, which the internet indicates is still equipped with Ribbon/Genband/Nortel DMS-100/200 switches but has no public office.

There was a time when you had to dial 1 before a number to signal to the routing system that a call would be going outside the area code. But that is pretty much obsolete in the USA these days, at least when using a cell phone.

Landline Decline

Marshall McLuhan advised: “Obsolescence never meant the end of anything, it’s just the beginning.”

In 2007, I finally cancelled my old-style landline phone, briefly switched to Vonage, and then I went fully cellular in May 2009. So I said goodbye to the old EDison exchange and, since my original cell phone was with U.S. Cellular, joined the 440- exchange. I left U.S. Cellular a few years later, when I purchase my first iPhone, as AT&T was the only carrier for the iPhone at the time. But number portability meant I was able to remain with my old number in the 440- exchange. When my wife bought her first iPhone years later, it was through AT&T and that put her in the 766- exchange along with other new AT&T accounts. Thankfully our marriage has survived our being in different telephone exchanges, something that would have been more challenging in the old landline days.

When I gave up my landline, only about 1 in 5 adult Americans had only cell phones. That has increased to well over 70% in 2024.

So most homes no longer have landline telephones. When I was young we would receive an immense phone book each year in Oklahoma City. My mother would keep it on one of the seats at the dinner table to boost me up so that I could eat more comfortably. In the 1970s, it expanded into two separate books, each several inches thick, one with white paper phone listings and another with yellow pages of business listings and advertisements. When I moved to Bartlesville, the thinness of the local telephone book was only one of several lifestyle changes. The latest phone book was left beside our mailbox the other day, and it sure seems like a relic.

But time marches on, and now when we “reach out and touch someone”, most of us do that wirelessly and give little thought to an old meaning for “exchange”. In 2024, AT&T announced that by 2029 it would abandon landline service across 20 states, including Oklahoma.

Thank you for this article. I grew up outside Dewey with a party line. Secretly listening; sorta.

I never called Bartlesville because it was long distance, and I would have received a scolding.

Oh my, how far I’d tried to stretch the telephone cord; winding it around my finger as I talked. If you were fed up with someone you were talking to just slam the phone on the receiver. They got the point. I had to memorize girlfriend’s numbers; rather useless now. If I loose my cellphone now, Katy bar the door, I’m in trouble. Again, you brought back wonderful memories of “phone calling”