Five years ago, in early 2020, interest in the concept of internal monologues spiked after a viral tweet shared how not everyone experiences the phenomenon, which has been described as hearing your own voice talking inside your head, in complete sentences, verbalizing your thoughts.

That prompted Ryan Langdon to post a video interview with a lady who had no such inner monologue, and I remember seeing it at the time. I had missed the tweet because I have always minimized my engagement with Twitter, now called X. I didn’t pay much heed to Langdon’s post, and the statewide shutdown of public schools the next month, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, drove the topic from my mind…which has no inner monologue.

Half a decade later, I saw another mention of the phenomenon, so I finally returned to the topic, taking the time to read descriptions of it. Unsure about my interpretation, I asked my Facebook friends if some of them experienced it. Personally, while I can imagine someone’s voice speaking a given sentence, I don’t recall ever spontaneously hearing such a thing in my head, save for famous media moments, such as FDR’s comments about the attack on Pearl Harbor. I certainly never hear my thoughts being verbalized internally in my own voice.

Immediately several friends confirmed that yes, they hear their thoughts in their head, “spoken” in their own voice. Some experience it frequently.

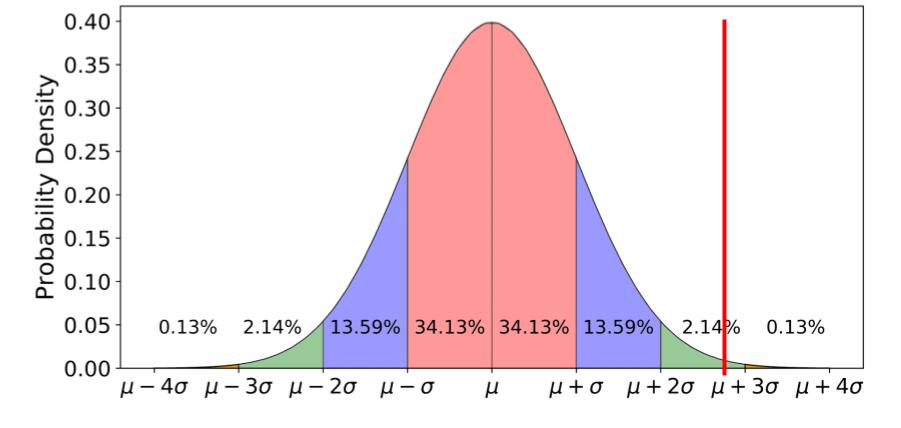

My psychology background merely consists of a three-credit-hour introductory psychology course and a two-credit-hour educational psychology course almost 40 years ago, plus applying Piaget’s theory of cognitive development in science learning cycles. So I have little understanding of the types of inner thought. Reading that 30-50% of people commonly experience “inner speech” led me to explore the concept and its possible implications in my life.

Types of inner experience

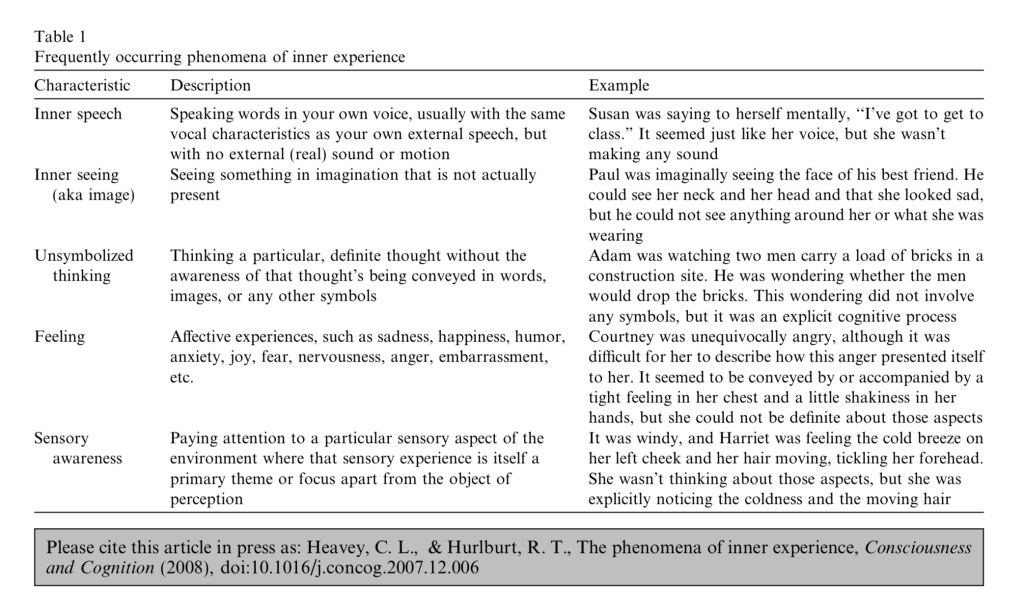

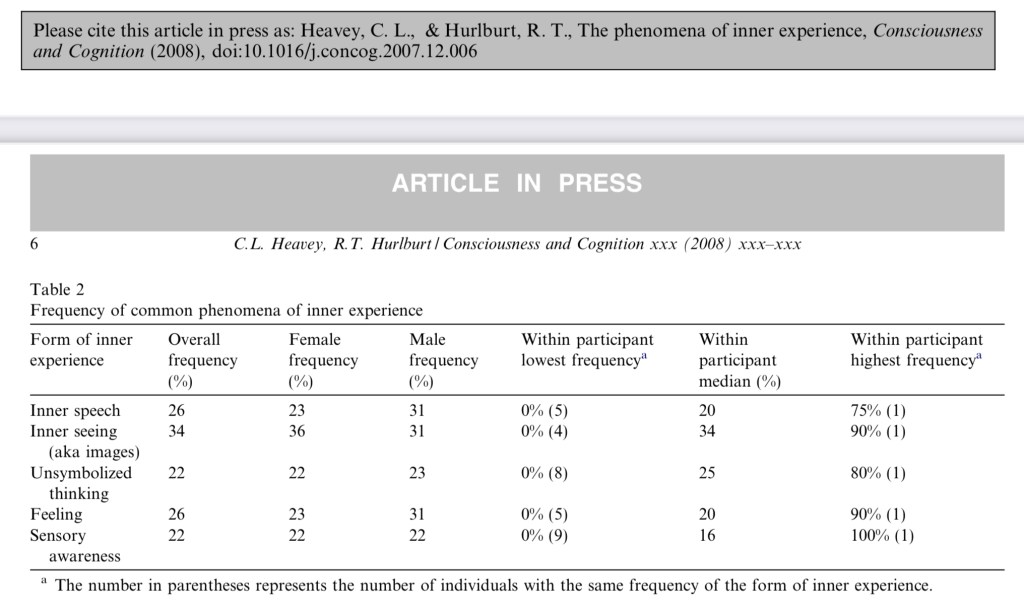

Back in 2007, C.L. Heavey and R.T. Hurlburt identified five frequently occurring phenomena of inner experience, including “inner speech”.

They demographically selected 30 subjects from a pool of over 400 undergraduate students, training them in descriptive experience sampling before equipping them with beepers that triggered randomly to have them note their inner experiences ten times over two days. The subjects might be engaging in simultaneous forms of inner experience at any given moment, so the overall frequencies of the experiences added to over 100%.

I find it fascinating that overall the subjects were engaged in inner speech about 1/4 of the time, although 1/6 of them never experienced it. Hurlburt’s years of research have led him to state that few, if any, people actually engage in inner speech continually, but in some people it can be rather frequent.

I never experience inner speech, but I am familiar with all of the other inner experiences in Heavey & Hurlburt’s study. While I’ve read that some people lacking inner speech also report aphantasia, the inability to visualize mental images, I do not have that rare neurodevelopmental trait. However, rather than inner seeing, I mostly engage in unsymbolized thinking that lacks words, images, or any other symbols.

CAUTION: Scientific jargon ahead, but thankfully it only lasts for two paragraphs.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, the Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development claimed that inner speech resulted from a developmental process, with children’s linguistically mediated social interactions changed into an internalized “conversation” with the self. Other theorists have argued that it plays a role in reasoning, facilitating abstract thought, etc.

The brain is said to have dorsal and ventral language streams, with the dorsal developing more slowly in childhood and influencing the emergence of inner speech. So it could be that the way my own dorsal stream matured is what prevents me from having an internal monologue.

Personal implications

Throughout my life, I’ve seen portrayals in movies and television of people thinking on screen with a voiceover narration by them of their thoughts. I had always presumed that was just a contructed method of conveying their abstract thoughts, their unsymbolized thinking. Now I realize that for a significant fraction of people, it represents what they actually experience internally.

That is truly strange to me, and it is no surprise that those with an inner monologue may struggle to imagine how people like me think. Perhaps descriptions of unsymbolized thinking would help some of them recognize it as an inner experience they also have, and that would help them understand my most common inner experience.

IQ and Processing Speeds

Otherness is often misrepresented as inferiority, and I’ve seen silly comments, thankfully not from my Facebook friends, that those lacking an inner monologue must be “smooth-brained” or have lower IQs. I’ve also seen on some message boards speculation that an inner monologue slows processing, since the rate of the spoken word lags the typical comprehension rate. I question the validity of such assertions.

The Intelligence Quotient is itself a problematic concept. It claims to measure a person’s cognitive abilities, particularly the capacity for reasoning, problem-solving, and learning. While IQ tests correlate well with academic success, their ability to assess intelligence in a broader sense is highly questionable. The eminent Stephen Jay Gould despised IQ scores, criticizing in The Mismeasure of Man their development and use, charging they reflect two major fallacies: reification, or, “our tendency to convert abstract concepts into entities” and ranking, our “propensity for ordering complex variation as a gradual ascending scale.”

When I was an undergraduate, I participated in a psychological research study that included being administered the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale examination, and my overall score was at the 99.44 percentile. That matches up with the IQ score I received on a test in grade school. So my lack of an inner monologue didn’t prevent me from having a high IQ, although how much that means is highly debatable, and one should not confuse intelligence for wisdom.

As for processing speeds, some of my Facebook friends commented how subvocalization could hinder their reading speed. I was a very fast reader as a child, racing through 135 books in first grade, exhausting our K-3 school library before I graduated from third grade, and finishing the SRA box of readings and comprehension tests months early in my sixth grade reading class, which greatly frustrated our teacher. I have never “heard” voices when reading, which I suppose might have sped me along without reducing my comprehension. However, as I have aged, the speed at which I read for pleasure has slowed greatly, and my attention span and stamina have shortened.

Internal Dialogues

Of greater interest to me is that around 80% of people report hearing an “inner voice” when reading silently, and over half report hearing distinct character voices most or all of the time. I’ve never had that experience, and I will now wildly speculate on its possible impacts on me. I haven’t tried to back any of the following with scientific evidence.

In junior high and high school, I greatly disliked reading plays in literature class, but I was fine when they were performed, either just vocally or in a live or recorded performance. I suspect that not “hearing” the play internally was a block. I suffered my way through reading Julius Caesar, and I didn’t enjoy it until we watched the 1953 epic movie version. I was grateful that we read the play Death of a Salesman aloud in class, despite the faltering readings of some students, as otherwise I would have had no appreciation for it. I didn’t enjoy reading the play The Crucible, but watching it was a treat. However, after reading the novel The Scarlet Letter, watching a movie adaptation of it did nothing for me.

In 1984, when I was in Washington, DC as a U.S. Presidential Scholar, we toured the Folger Shakespeare Library, but I couldn’t imagine why anyone would want to own a single copy of the First Folio, let alone collect 82 of the 235 known surviving copies. I’d be willing to endure a condensed Shakespeare play, and I admire many of his perfect creative expressions and several of his sonnets, but reading a Shakespeare play is torture for me.

As a youngster, I not only loved to read novels and nonfiction, but I also loved to write essays and articles. I would bang out a family newspaper on our manual typewriter, and I was enthusiastic about editing an elementary school magazine. So when I was ten years old, my father engaged a university student as a creative writing tutor for me. She put me through a variety of exercises, but the dialog I wrote was nothing but dreadful cliches. To this day, I have no “ear” for dialog.

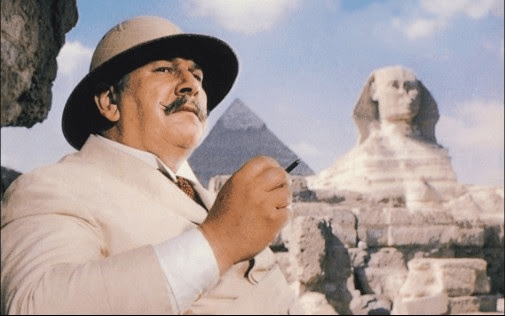

Decades later, when I was going on weekly day hikes, I started checking out audiobooks on cassette tape to listen to on the long drives and sometimes while hiking. I exhausted the downtown Tulsa library’s collection of Ellis Peters and Elizabeth Peters audiobooks and eventually sampled Agatha Christie. I’d seen Peter Ustinov’s movie portrayals of her detective character Hercule Poirot, and I’d read a couple of her books. They hadn’t made much of an impression, but I was dumbfounded when I listened to her audiobooks at how believable and engaging her dialog could be even when directly narrated from the text. After that, I never read another Christie book, but instead I listened to all 66 of her novels and her 153 short stories in audiobook form.

I have tried to read screenplays, but I find I hate them, and when I am reading a short story or a novel, I don’t form a sharp mental image of the characters, even though I might visualize the settings. My dreams are in color and often have detailed settings, scenarios, and some dialog, but I retain no memories of the sound of any vocalizations. When I see movie or television adaptations of books, I am seldom put off by how an actor looks or talks, unless it clearly violates a description of the character in the text, and my mental image of a character subsequently takes the form I saw in the visual medium. If I see multiple portrayals, I stick with my favorite. I was always puzzled when people who had read a book would watch a movie adaptation and remark, “That isn’t how I visualized him/her.” I had barely visualized them at all, and I certainly never created a voice for them in my head.

All of this has greatly affected my own writing. My essay writing earned me various recognitions, but I have always resisted writing short stories, novels, or plays — anything with dialog — instead sticking with essays, research papers, travelogues, and the like. This blog currently consists of almost 800,000 words across almost 800 posts…with almost no dialog.

So if you have an internal monologue, I hope that you enjoy it, and that it speaks to you kindly and gently. My thoughts, in the form of unsymbolized thinking, are with you.