Flags are inherently symbolic, with meanings often both subtle and mutable. The associations of colors shift over time and vary among cultures. In the Byzantine Empire, the Blues and Greens chariot racing groups evolved into powerful political and social factions, with the Blues often representing the upper classes and religious orthodoxy while the Greens represented the lower classes and Monophysitism. Their rivalry even led to riots and civil wars.

For the majority of my life, a Red was a Communist, not a Republican. Traditional political mapmakers often used blue for states that voted primarily Republican and red for Democratic strongholds. However, the close Presidential election of 2000 put color-coded maps of which states’ electoral votes were for each candidate before television viewers over an extended period, and the major media outlets began conforming to a scheme coding Democratic states blue and Republicans red, and that has become a fixture of politics for decades.

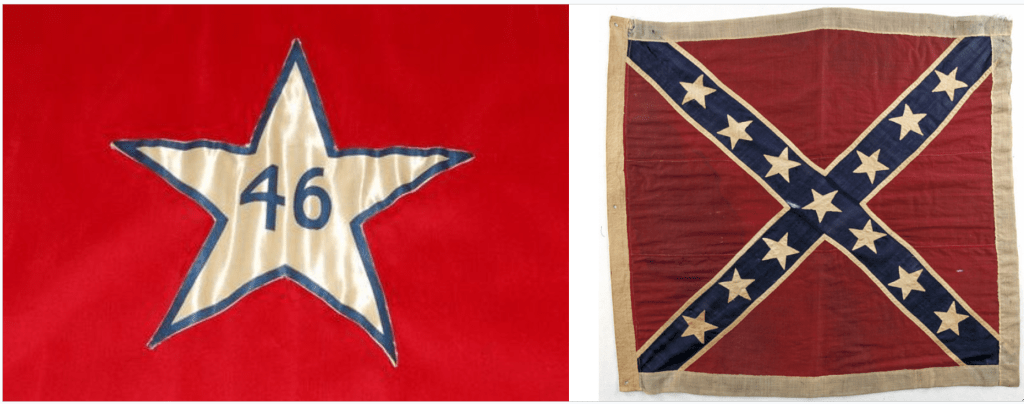

Which brings me to Oklahoma’s latest license plates, of all things. Last September the state began circulating a new default design. Lt. Governor Matt Pinnell and Service Oklahoma decided to base it on the state’s first flag, adding the current tagline and some tiny silhouettes.

I’m sure that Pinnell liked the bold and simple design, and maybe, just maybe, as one of the many Republicans who dominate our state government, he also liked the idea of a red plate in this oh-so-very-red state. [Weeks after this post, it was revealed that Governor Stitt was the person responsible for this design. Imagine that.]

The state’s license plates from 1989 to 2008 also borrowed from a state flag, but from the one we have had since 1925, by featuring its Osage war shield crisscrossed with a calumet and an olive branch. I liked those plates, and I didn’t mind when “Native America” was added to them from 1995 to 2008.

Those were replaced from 2009 to 2017 by plates inspired by Allan Houser’s Sacred Rain Arrow sculpture. The U.S. Supreme Court declined to reconsider a court of appeals ruling that threw out a lawsuit against them filed by a Christian pastor from Bethany. He alleged the image symbolized that there were multiple gods and the arrow was an intermediary for prayer. The 10th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that a “reasonable observer” would not draw such conclusions when viewing the plates.

I agree, and if the pastor were truly offended by the plate, he could always pay for a specialty plate in some other design. In his case, the state’s “In God We Trust” plate would be an obvious possibility, but as of 2025 there would be over 140 other choices, and even more if one can provide certain documentation.

I had my own objections, albeit based on aesthetics and not symbolism, to the next plate that adorned our cars by default, which featured a white scissortail flycatcher silhouette on a background of blue mountain forms. I just didn’t care for it, so I purchased a State Parks Pavilion specialty plate.

I liked that design, and how a portion of the fee is deposited with the Oklahoma Tourism and Recreation Department, which I worked for back in 1985. That brings us to 2024 when the latest default plate began to be distributed, and I do have a symbolic objection to it.

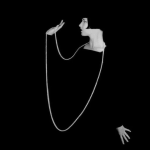

The flag it is based on was adopted four years after statehood in 1911, and it was designed by Ruth D. Clement, who just so happened to be a founder of the state branch of the Daughters of the Confederacy. I doubt it is a coincidence that Ruth designed a red field with a white star offset by blue, which are also elements of the Confederate battle flag.

Mind you, other state flags have or had far more apparent Confederate symbolism. Take our neighbor to the east, Arkansas. It was part of the Confederacy, and the state flag it adopted in 1913 deliberately adapted multiple elements of the Confederate battle flag, shifting from a cross to a diamond shape to represent that at the time it had the only diamond mine in North America. If that wasn’t obvious enough, its legislature deliberately added another star in 1923 to the white field of the diamond that was specifically meant to represent the Confederacy. Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, and Florida also have or had state flags which were obvious Confederate symbols.

As for Oklahoma, its history is grounded in racial cleansing, and some of its displaced First Peoples were themselves slaveowners who dragged their black slaves along on their trails of tears. That putrid state of affairs helps explain why Senate Bill One, the symbolic first bill of the state senate in 1907, was a Jim Crow law that required separate coaches in all public rail cars for “the white and negro races” along with separate waiting rooms in each railroad depot.

Oklahoma’s history of racism is long, ugly, and brutal. In 1917, just five miles north of where I now live, a white mob in Dewey burned the homes of at least 20 black families, and four years later Tulsa had a race massacre 40 miles to the south. I’m pretty confident those occurred in a state flying a flag with subtle Confederate symbolism.

So why did Oklahoma abandon what I presume was its little nod to the Confederacy? Well, there was a Red Scare after World War I, and that was a fear not of rabid right-wingers but of communists and radical leftists. The often-embarrassing Oklahoma legislature passed a silly law in 1919, which lives on today as OS 21 § 374:

Any person in this state, who shall carry or cause to be carried, or publicly display any red flag or other emblem or banner, indicating disloyalty to the Government of the United States or a belief in anarchy or other political doctrines or beliefs, whose objects are either the disruption or destruction of organized government, or the defiance of the laws of the United States or of the State of Oklahoma, shall be deemed guilty of a felony, and upon conviction shall be punished by imprisonment in the Penitentiary of the State of Oklahoma for a term not exceeding ten (10) years, or by a fine not exceeding One Thousand Dollars ($1,000.00) or by both such imprisonment and fine.

Need I state the irony here?

In 1924 the Oklahoma Society Daughters of the American Revolution sponsored a competition to design a new state flag. Louise Funk Fluke of Shawnee designed a blue field with a centered Osage war shield with six painted crosses and seven pendant eagle feathers, overlaid by the peace pipe and olive branch. That’s plenty of symbolism that I don’t find objectionable.

My dilemma is similar to that once faced by the Bethany pastor. I don’t like the new plates which surround me, but a “reasonable observer” would not view them and draw my conclusions. So I don’t care if someone uses the default plate, but I’ll certainly continue to shell out the bucks each year to renew my State Parks Pavilion specialty plate. Maybe I’ll pretend the “46” on the plates doesn’t refer to Oklahoma being the 46th state in the union, but are rather an homage to our 46th President. That would be a hoot.

If you find my take on the symbolism of our plates silly, more power to you. After all, symbols are mutable. An example are the swastikas which adorn the 1920 road bridge in Bartlesville’s Johnstone Park. They were First Peoples symbols for good luck that pre-date the Nazi regime and its different version of the symbol.

In 1925, Coca Cola used the swastika in advertisements, the Boy Scouts once used the symbol, and the Girls’ Club of America once called their magazine Swastika and sent swastika tokens to young readers.

The 45th Infantry Division of the National Guard, most associated with the Oklahoma Army National Guard, originally had a swastika as its symbol as a tribute to the large First Peoples population in the southwestern U.S.

However, the rise of the Nazi party in Germany, which used the swastika symbol pointing clockwise and tilted to stand on one point, led to that symbol and its variants being shunned elsewhere. Coke, the Boy Scouts, and the Girls’ Club dropped it, the 45th Infantry Division switched to a thunderbird, and Bartlesville now has signage explaining its bridge symbols. They didn’t have to do those things, since their swastikas didn’t fully echo the design of the Nazis, but like me with the original Oklahoma flag, it made them, shall we say, uncomfortable.

And now we know that Stitt wanted this design, no one else really did.

https://ktul.com/news/local/new-oklahoma-license-plate-design-faces-scrutiny-focus-group-preferred-alternative-design-46-star-icon-imagine-that-open-records-request-oklahoma-tourism-and-recreation-department-lt-governor-matt-pinnell-focus-group-public-feedback-guardian-design