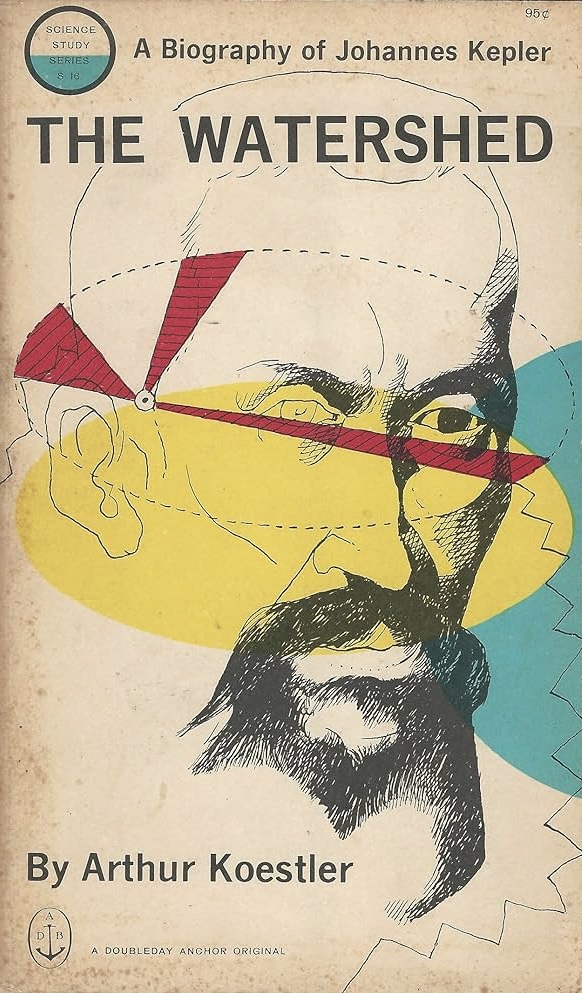

Long ago, early in my years of teaching high school physics, I came across an old paperback book from 1961, The Watershed, with a cover that showed Johannes Kepler and an illustration of his first and second laws of planetary motion.

I snapped up the biography, enjoying it immensely. I used it to flesh out my lectures on our evolving understanding of the cosmos when we studied universal gravitation. A few years later, revisiting this entry in The Science Study Series, I noticed that it was actually an excerpt of a larger work of 1959, The Sleepwalkers.

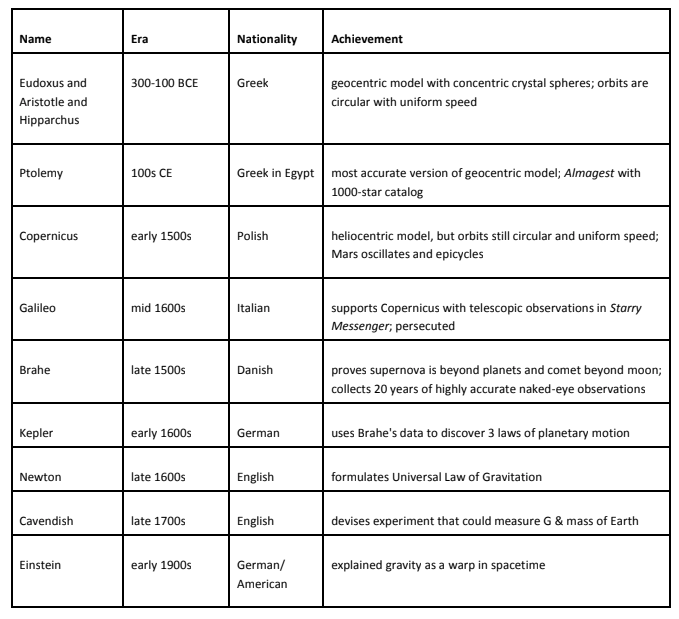

I sought that out, devouring the thick tome, which was so interesting that it, along with Timothy Ferris’s Coming of Age in the Milky Way, led to me devoting a week of my course each year to the progress from Eudoxus in 300 BCE to Einstein in the early 1900s CE.

The author of The Sleepwalkers, Arthur Koestler, is best known for his book Darkness at Noon. From my introduction, you might guess it is about astronomical eclipses, but you would be wrong.

Koestler led a most interesting life. He was born in Budapest in 1905, studied engineering for awhile in Vienna, but when his father’s business failed, Arthur left for Palestine. He edited a German and Arabian weekly newspaper in Cairo, and became a journalist who traveled extensively.

In the early 1930s, he moved to the Soviet Union for a few years and was an active communist from 1931 to 1938. He participated in anti-fascist movements, and as a war correspondent in Spain during its Civil War, he was imprisoned, sentenced to death, but then released in a prisoner exchange.

Back in France, he struggled to make a living and agreed to write a sex encyclopedia, but his crooked cousin was exploiting him and Koestler only received a flat payment of 60 pounds for a work that sold in the tens of thousands.

In 1938, he resigned from the Communist Party, disillusioned by Stalin’s show trials of 1936 to 1938. Koestler was electrified by the confessions of Nikolai Bukharin, a popular and highly intellectual Bolshevik leader he had met in Russia. How could Bukharin and other defendents have been manipulated to confess to crimes they had clearly not committed? Why had the victims of Stalin’s coup de théâtre played their parts so willingly and gone so obediently to their deaths?

That led him to write an anti-communist novel while living in Paris with 21-year-old British sculptor Daphne Hardy. She translated his manuscript from German into English and smuggled it out of France when they fled ahead of the Nazi occupation of Paris. She fled to London, while Koestler joined the French Foreign Legion to hide his identity. For decades, her English translation was the only manuscript of the book known to have survived.

Koestler deserted the legion in North Africa, heard a false report that Hardy had died when her ship to Britain had been sunk, and tried unsuccessfully to commit suicide. He finally turned up in Britain without an entry permit and was imprisoned. He was still in prison when Hardy’s English translation of his novel was published in early 1941. It would make him famous.

Hardy was the one who had named the book Darkness at Noon. Koestler thought the title had come from a well-known line in Milton’s Samson Agonistes, “Oh dark, dark, dark, amid the blaze of noon,” but actually Hardy was inspired by a line from the book of Job: “They meet with darkness in the daytime, and grope in the noonday as in the night.”

The novel was a sensation, selling half a million copies in France alone and preventing the French Communist Party from being elected to join the government. Within a few years its surviving English translation had been re-translated into over thirty more languages, including a German version by Koestler himself.

Michael Foot, a future Labour Party leader in Britain, wrote, “Who will ever forget the first moment he read Darkness at Noon?” George Orwell thought the book was a brilliant novel and accepted its explanation of the show trials, impressed by the accuracy of its analysis of communism. Four years later, when Orwell was writing Animal Farm, he would pronounce Darkness at Noon a masterpiece.

Koestler’s original German manuscript of the novel, a carbon copy of which had been sent to a Swiss publisher as he and Hardy fled France, was considered lost until 2015, 32 years after Koestler’s death. A doctoral candidate working on Koestler’s writings stumbled across it in the archive of the founder of a Swiss publishing house. Its original title of Rubaschow, the German spelling of its protagonist, had likely prevented it from being identified earlier.

Hardy’s translation was compared to the original German, and revealed that Koestler had made some last-minute changes and his original included some passages not found in her translation. So the original manuscript was published, and that was translated into English by Philip Boehm.

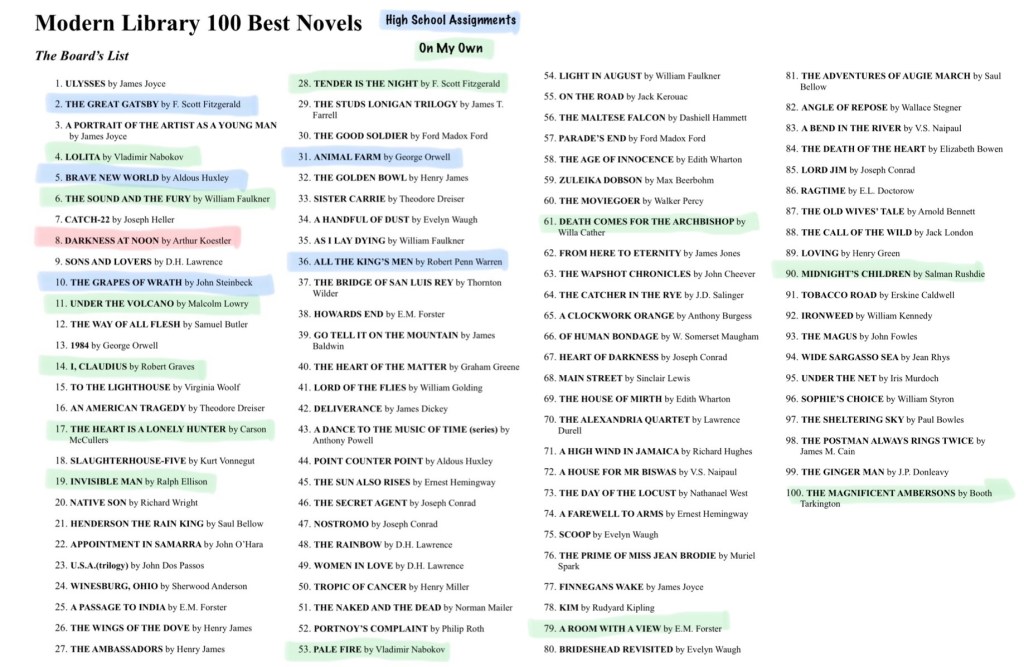

Back in 1998, the Modern Library imprint of the Random House publishing firm polled its editorial board for their opinions of the best 100 English-language novels published during the 20th century. Darkness at Noon was ranked #8. Some years ago, I began marking off entries I had read in school and on my own.

That inspired me to read Lolita and Under the Volcano in 2011, Pale Fire in 2017, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter in 2019, and A Room with a View in 2023.

Living under increasingly repressive state and federal governments in 2025, I decided it was time for Darkness at Noon. Would its message be as relevant to the populist autocracy that demagogues are creating in our country as it was to communist and Nazi regimes in the twentieth century?

I purchased the Kindle edition of the new translation by Boehm. It seemed like a relatively quick read, and my curiosity led me to compile these statistics on the reported word counts of the books I’ve read on the Modern Library list:

- The Great Gatsby: 47,094

- Lolita: 112,473

- Brave New World: 64,531

- The Sound and the Fury: 81,500

- Darkness at Noon: 78,944

- The Grapes of Wrath: 169,481

- Under the Volcano: 144,000

- I, Claudius: 100,000

- The Heart is a Lonely Hunter: 121,960

- Invisible Man: 95,000

- Tender is the Night: 104,925

- Animal Farm: 29,500

- All the King’s Men: 286,000

- Pale Fire: 95,000

- Death Comes for the Archbishop: 72,000

- A Room with a View: 65,000

- Midnight’s Children: 208,000

- The Magnificent Ambersons: 104,000

I found the story gripping, with its narrative increasingly confined as it progressed from one prison interrogation to the next. It certainly provides insights into totalitarian regimes and the intellectual traps that ensnared some early communist leaders.

But the Guardian’s William Skidelsky correctly notes that, “…today Koestler is a strangely marginal figure. Why is this? Partly, or perhaps precisely because he was so much a creature of the 20th century. The battles he fought are no longer quite our battles, and he seems sealed off from us by all that has happened since his death in 1983 – most notably, of course, the collapse of communism.”

The Greatest Books, which uses a meta-analysis of many reading lists to create its rankings, currently ranks the work as the 269th greatest book of all time.

The most relevant section of the book to our time was when Koestler, in the guise of his protagonist, outlined his “theory of the masses” in a long diary entry Rubashov composes in his cell before his final interrogation:

One hundred fifty years ago, on the day the Bastille was stormed [July 14, 1789], the European swing once again lurched into motion after a long period of inertia, with a vigorous push away from tyranny toward what seemed an unstoppable climb into the blue sky of freedom. The ascent into the spheres of liberalism and democracy lasted a hundred years. But lo and behold, it gradually began to lose speed as it came closer to the apex, the turning point of its trajectory; then, after a brief stasis, it started moving backward, in an increasingly rapid descent. And with the same vigor as before, it carried its passengers away from freedom and back to tyranny. Whoever kept staring at the sky instead of hanging on to the swing grew dizzy and tumbled out.

That spoke to me as we grip our own American swing in its fall.

Whoever wishes to avoid getting dizzy must try to grasp the laws of motion governing the swing. Because what we are facing is clearly a pendulum swing of history, from absolutism to democracy, from democracy to absolute dictatorship.

The degree of individual freedom a nation is able to attain and retain depends on the degree of its political maturity. The pendulum swing described above suggests that the political maturity of the masses does not follow the same constantly rising curve of a maturing individual, but is subject to more complicated laws.

The political maturity of the masses depends on their ability to discern their own interest, which presupposes a knowledge of the process of production and the distribution of goods. A nation’s ability to govern itself democratically is consequently determined by how well it understands the structure and functioning of the social body as a whole.

We certainly have issues in discerning our own interests these days.

However, every technical advance leads to a further complication of the economic framework, to new factors, new connections that the masses are at first unable to comprehend. And so every leap of technical progress brings with it a relative intellectual regression of the masses, a decline in their political maturity. At times it may take decades or even generations before the collective consciousness gradually catches up to the changed order and regains the capacity to govern itself that it had formerly possessed at a lower stage of civilization. The political maturity of the masses can therefore not be measured in absolute numbers, but always only relatively: namely in relation to the developmental stage of any given civilization.

When the balance between mass consciousness and objective reality is achieved, then democracy will inevitably prevail, by either peaceful or violent means, until the next, nearly always volatile leap of progress—for example, the invention of gunpowder or the mechanized loom—again places the masses in a condition of relative immaturity and makes it possible or necessary for the establishment of a new authoritarian regime.

I would argue that the internet has become such a framework with profound social effects that are now increasingly compounded by artificial intelligence.

The process is best compared to a ship being lifted through a series of locks. At the beginning of each stage, the ship is at a relatively low level, from which it is slowly raised until it is even with the next lock—but this glorious stage is of short duration, as it now faces a new set of levels, which again can be attained only slowly and gradually. The sides of the chamber represent the objective state of technological advancement, the mastery of natural forces; the water level in the chamber symbolizes the political maturity of the masses. Any attempt to measure this as an absolute height above sea level would be pointless; what is measured instead is the relative range of levels in each lock.

The invention of the steam engine brought a period of rapid objective progress, and as a consequence, a period of equally rapid subjective political regression. The industrial era is still historically young, the gap still very great between its enormously complicated economic structure and the intellectual awareness of the masses. It is therefore understandable that the relative political maturity of people in the first half of the twentieth century is less than it was two hundred years BC or at the conclusion of the feudal period.

If Koestler’s theory is applicable, can we hope that over time the political maturity of the masses will adapt to the internet and artificial intelligence, and the collective consciousness can regain the capacity to govern itself, swinging us away from tyranny? Perhaps, but his theory says adaptation is very slow.

I’m glad I read Darkness at Noon, as it gave me additional metaphors to consider as I ponder a political climate that is increasingly unsettling and worrisome.

As for Koestler, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1976 and chronic lymphocytic leukaemia in 1980. Upon realizing that his cancer had metastasized, he and his third wife of 28 years, Cynthia Jefferies, killed themselves in 1983.

A domineering man who engaged in many sexual affairs and generally treated the women in his life badly, he admitted in his autobiography that he had denounced a woman he had a relationship with to the Soviet secret police, an episode that explains the character of Orlova, whom the protagonist Rubashov betrays to save himself. That act becames a symbol of his moral decay during his own trial, and Rubashov comes to recognize the sacredness of the individual which contrasts with the Party’s disregard for individual lives.

Does that in any way redeem Koestler? Given his behavior, should his writings be shunned, as some do now with those of Neil Gaiman and other problematic authors? I’m reminded of how Woody Allen’s own predilections were translated in his film Manhattan. I generally choose to enjoy a work on its own merits, regardless of the virtuous or wicked actions of its creators. I’m glad I read Darkness at Noon, which sounds with the ring of truth.