After leaving OKC, we rolled along Interstate 40 from OKC to Amarillo, Texas. About a decade ago, we visited a couple of attractions along the way: the Heartland of America Museum in Weatherford in 2015 and the Route 66 Museum in Elk City in 2014. Thus far I’ve resisted Weatherford’s Stafford Air & Space Museum since I’ve seen plenty of similar items at the Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas and the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum in the District of Columbia.

This time, as we approached the Texas border a two-hour drive west from OKC, we deviated onto one of the I-40 business routes, which are really just original Route 66, to visit little Erick, Oklahoma. It is less than a mile south of the interstate, but it seems farther, given the town’s desolation.

Erick was doing okay a century ago. The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture offers, “By 1909 travelers who stayed at the Hotel Crescent found a bustling community with thirteen general stores, two hardware stores, several cotton gins, blacksmith shops, a livery, a harness shop, and a lumber store. Food commodities could be purchased at five meat markets, several grocery stores, a bakery, and a confectionary. The town supported two banks and two weekly newspapers, the Beckham County Democrat and the Erick Altruist.”

The town peaked with 2,231 souls in 1930 amidst an oil boom, but it has now diminished to less than a thousand and seems much smaller given the few surviving businesses. We turned off Roger Miller Boulevard onto Sheb Wooley Avenue, but we found virtually no commerce or traffic.

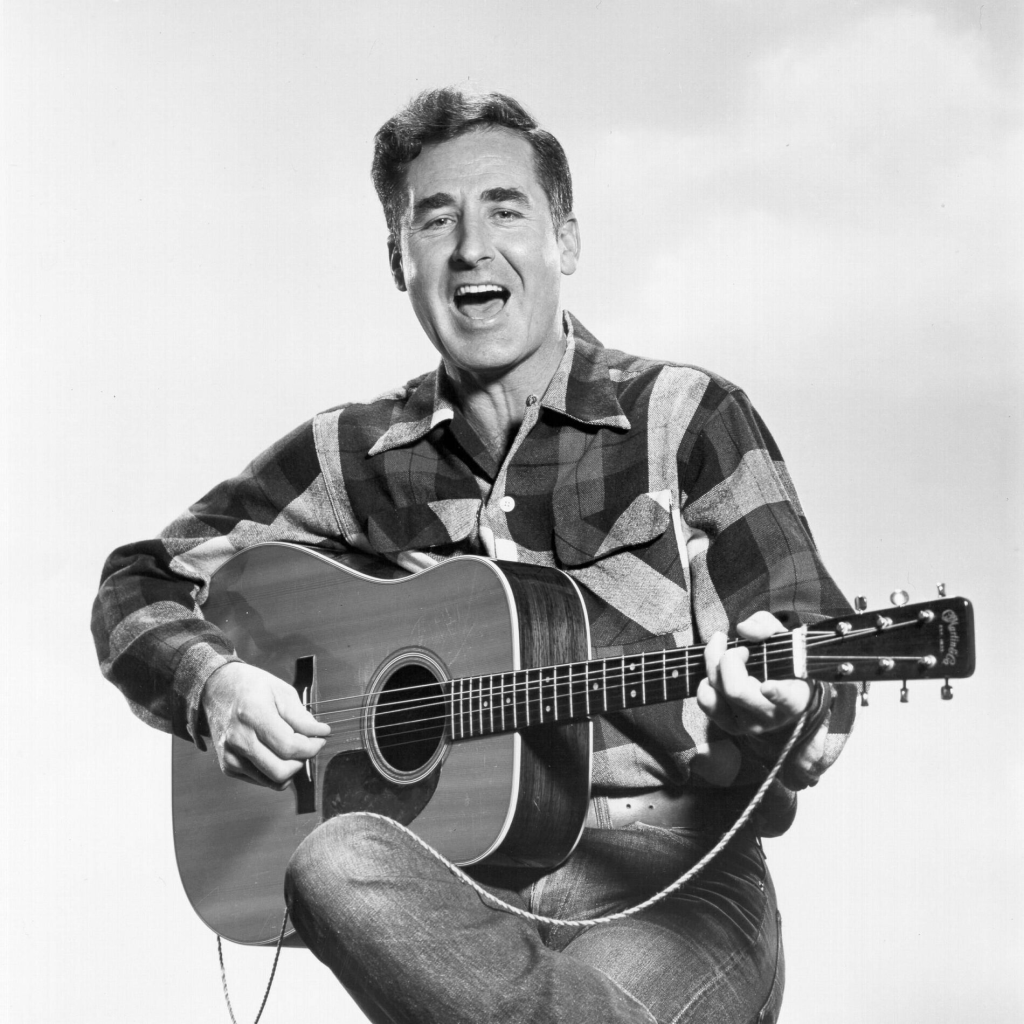

Those street names might bring back memories for those of mine and earlier generations, as Erick was the hometown of two successful singer-songwriters.

King of the Road

Roger Miller grew up on his aunt and uncle’s farm outside Erick, picking cotton and plowing. The farm had no telephone until 1951, and Miller attended a one-room schoolhouse as an introverted child who often daydreamed or composed songs.

He listened to the Grand Old Opry and Light Crust Doughboys on a Fort Worth radio station with his cousin’s husband, Sheb Wooley. Wooley taught Miller his first guitar chords and bought him a fiddle. Wooley, Hank Williams, and Bob Wills inspired Miller to become a singer-songwriter.

At age 17, he stole a guitar out of desperation to write songs, but he turned himself in the next day and enlisted in the army to avoid jail. Always funny, Roger quipped, “My education was Korea, Clash of ’52.”

After leaving the army, Miller traveled to Nashville and met Chet Atkins, who asked to hear him sing. Atkins had to loan Miller a guitar, since he did not own one. Miller was so nervous that he played the guitar in one key and sang in another, prompting Atkins to advise him to come back later after he had more experience.

Miller became a singing bellhop at Nashville’s Andrew Jackson Hotel and was eventually hired to play the fiddle in Minnie Pearl’s band. He then married and became a father, and that prompted him to become a fireman in Amarillo for steadier work while still performing at night. He claimed that there were only two fires during his service, one in a chicken coop and another that he slept through, after which the department “suggested that…[he] seek other employment.”

Miller returned to Nashville and wrote songs for Ernest Tubb, Faron Young, and Jim Reeves, becoming one of the top 1950s songwriters. He went on to perform songs that hit the country charts, including his biggest hit, King of the Road.

Miller was a terribly funny, talented, and undisciplined mess. He married three times, fathered eight children, and abused alcohol and amphetamines. A lifetime cigarette smoker, he died of lung and throat cancer in 1992 at age 56.

During one interview, Roger’s hometown of Erick was mentioned. The interviewer, understandably unaware of its location, asked what it was close to. Roger quipped, “Extinction.”

A Comedic and Dramatic Actor, Singer, Writer, and…Screamer

However, little Erick not only produced Roger but also the aforementioned Sheb Wooley. He formed a band at age 15 and periodically performed on an Elk City radio station 30 miles to the northeast of Erick.

Sheb was also a working cowboy and accomplished rodeo rider, but when the U.S. entered World War II and Sheb tried to enlist in his early 20s, he was rejected because of his numerous rodeo injuries. He became a welder and worked in the oil industry.

He moved to Fort Worth in 1946 and earned a living as a country-western musician, traveling across the South and Southwest. He moved to Hollywood in 1950, hoping to establish himself as an actor or singer in film or television.

He appeared in many TV westerns, including The Lone Ranger, The Adventures of Kit Carson, The Range Rider, The Cisco Kid, My Friend Flicka, Cheyenne, and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp. In 1958, he earned some fame with his rock-and-roll comedy single, The Purple People Eater.

Sheb hit his big break when he was cast as the drover Pete Nolan on Rawhide, writing and directing some of the episodes, and he later became a regular on Hee Haw, writing its theme song. He was the Country Music Association’s Comedian of the Year in 1968, 1992 Songwriter of the Year, and won the Western Heritage Award for nine consecutive years for his work in film and television westerns.

Sheb managed to outdo Roger in his number of marriages: five to Roger’s three. He never stopped writing; he recorded his last written song just four days before his death in 2003 at age 82.

The strangest of Sheb’s legacies is the “Wilhelm scream” which he recorded for the film Distant Drums.

The stock recording of the distinctive scream became an inside joke in the sound effects world and has been used in over 200 films.

Sandhills Curiosity Shop

A sight to behold in Erick is the Sandhills Curiosity Shop. The oldest brick building in town, it was once the City Meat Market and is now festooned with old advertising signs. It has been described as “a shop where nothing is for sale and its greatest curiosity is its owner, Harley, the Mediocre Musicmaker”. For context, see this 2016 post by author and photographer Rhys Martin or watch Harley in action; he helped inspire the Tow Mater character in the Pixar movie Cars.

We didn’t try to see if the mercurial Harley was around, just pausing long enough for me to take a photo of one side of the building which featured an old Cities Service sign. My father worked for Cities Service Gas Company and its successors from 1951-1983. That was the corporation’s natural gas division, which had its own variant of the logo, adding a flame to the interior of the triangle.

Mounting Losses

Oklahoma’s rural population has long been declining in the western portion of the state, which is part of the Great Plains. Over the past half-century, many counties in that swath across the central portion of the continental United States have lost over 60% of their former populations.

In recent years, the population loss has spread across other rural areas as Americans increasingly shift to urban centers.

The depopulation of the Great Plains is tied to a shift from small-scale subsistence farming to large commercial farms. I now dread traversing western Oklahoma and Kansas, eastern Colorado and New Mexico, and the Texas panhandle when we seek out higher elevations in Santa Fe, New Mexico or southwestern Colorado to escape the heat and humidity of summer in eastern Oklahoma.

One strategy I employed on this trip and a previous one when crossing the Oklahoma or Texas panhandles is to play my favorite Bob Wills album, Together Again… with Tommy Duncan. The mix of pathos and pleasure just fits. It features Dusty Skies, a beautiful song he first released in 1942.

Cindy Walker

The song was written by Cindy Walker, who had top-10 hits spread over five decades. She wrote Dusty Skies in the mid-1930s, as a Texas teenager inspired by newspaper accounts of the dust storms of the American prairies. Her father was a noted hymn writer, and her mother was an accomplished pianist.

Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys eventually recorded over fifty of her songs, including Bubbles in My Beer. Walker also wrote You Don’t Know Me, which was memorably recorded by Ray Charles. Her own recording of it is not as well known.

Her custom was rising at dawn each day to write songs, typing lyrics on a pink manual typewriter which she had hand-painted with flowers. Her widowed mother, Oree, lived with her and would help work out melodies to her daughter’s words.

Years ago, Wendy was touched when I first showed her Bob Wills’ fiddle at Oklahoma City’s National Cowboy and Western Heritage Center.

Someday I would like to visit the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, just so I might get to see Cindy Walker’s typewriter.