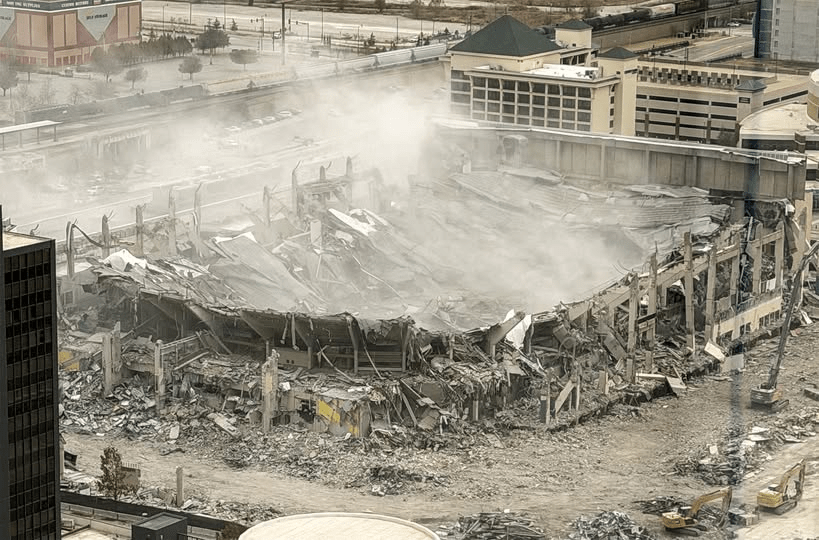

This week they really got going on destroying the old convention center in Oklahoma City. There was a dramatic photograph showing the arena bowl half destroyed, and then they brought the remaining roof down.

At the start of 2025, I wrote about the history of that huge facility, which was constructed from 1969-1972. It hosted my junior and senior proms and I gave a speech in it at my high school graduation. I also attended multiple conferences there over the years. The old Myriad is a few years younger than I am, but its time is up.

I’ll confess that it hurt a bit to see the former Allen Morgan Street Memorial Myriad Convention Center destroyed, despite its various shortcomings and obvious obsolescence. The pang I felt reminded me of a similar issue facing Bartlesville when I arrived here in 1989.

My Childhood Library

I’m a big fan of public libraries. I’d grown up using the Bethany branch of Oklahoma City’s Metropolitan Library System, and I remember checking out Curious George books there, along with Esphyr Slobodkina’s Caps for Sale. Years later, I prowled its shelves looking for science fair project ideas. I remember the giant checkers game in the children’s area that always caught my eye…but I’ll confess that I never learned to play checkers, let alone chess.

Another thing I noticed as I grew up was the simple elegance of the little branch’s architecture. It had opened in 1965 and was designed by Ray Bowman, the head of the Art Department at what was then Bethany Nazarene College, just blocks away. OkieModSquad posted a nice look back at it in 2017.

However, it was only 8,400 square feet and became woefully obsolete for the area’s needs. So it was replaced with a 23,000 square foot facility that opened in 2019, expanding its collection from 58,000 items to almost 90,000.

I have nostalgic memories of happily crossing the little bridge when entering or leaving one of my favorite places from childhood, but nostalgia is a trap. It is a good thing that they razed the old library and built a new and better one. It wouldn’t have made sense, given the money, the lot, etc. to try and expand the old library or repurpose it and build elsewhere.

Bartlesville’s Libraries

So let’s jump to 1989. I was 23 years old and had just moved to Bartlesville. Until then, I’d only caught glimpses of it along Highway 75 and over by Sooner High, since whenever we would head from OKC to Independence, Kansas to visit relatives, we would stop in Bartlesville to have lunch with some retired former coworkers of my parents; they lived in the Madison Heights addition.

I knew Bartlesville as an outlier town, awash in oil money, that produced lots of National Merit scholars and Advanced Placement students I had helped to recruit and advise while working in Scholars Programs at OU. Bartlesville had a symphony orchestra, a magnificent community center, a then-thriving shopping mall, and multiple skyscrapers, despite only having a population of 35,000. Surely its public library would be similarly impressive…right? Well, frankly, not at that time.

The First Bartlesville Library

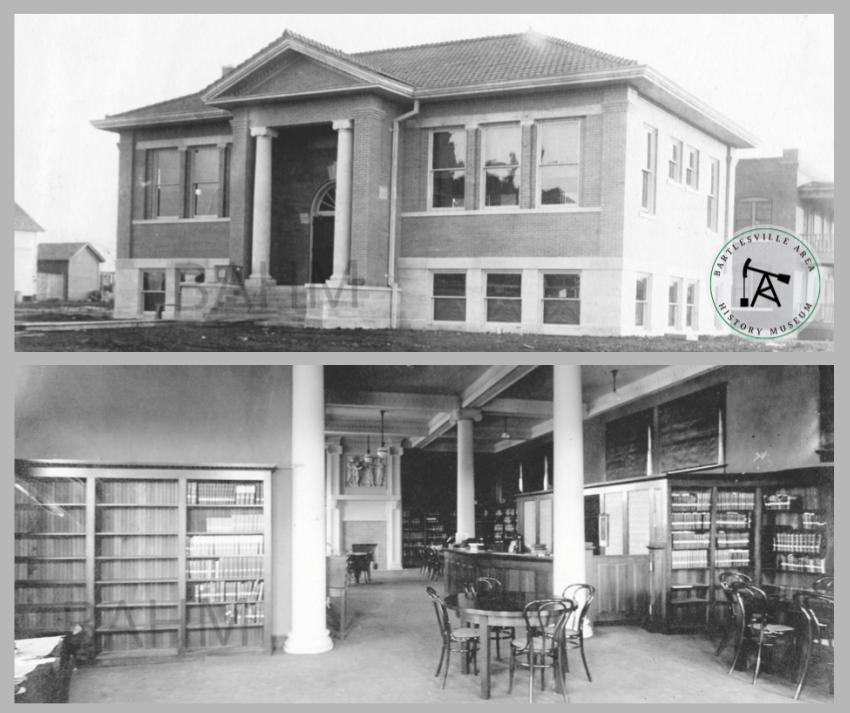

The former Carnegie Library building is just across Adams Boulevard from the Community Center. The town’s Tuesday Club had begun campaigning for a library in 1908, and the Carnegie Corporation provided a $12,500 grant to help build it.

The town grew from 6,000 in 1908 to 21,000 in 1927, and the library’s collection grew with it. From 1913 to 1927, it expanded from 1,250 volumes to over 10,000 and the building was bursting at the seams. In April 1927, a city election for a $25,000 library bond passed with over 75% approval: 2,155 to 689. Frank Phillips promptly pledged another $12,500 to the project, an unconditional gift for the library to use as it saw fit.

However, just days before the election, the Oklahoma legislature passed a law, taking immediate effect, that invalidated full-term bonds like the ones in Bartlesville’s election. That forced a revote in May for serial bonds, which earned over 82% approval: 1,407 to 298.

However, by July the state’s Assistant Attorney General held that the city had no statutory authority to issue bonds for a library. The city had already begun renovating the north wing of the Civic Center, which had opened in 1923, as a temporary home for the library while the original building was prepared for expansion.

The Second Bartlesville Library

The city library board decided against a third attempt at a bond issue, voting to have local architect Arthur Gorman draw up plans to remodel the ground floor of the Civic Center’s north wing into a permanent home for the library and rid itself of the Carnegie building. I’m guessing they were just relying on Frank Phillips’ unrestricted donation. The move would help popularize the relatively new Civic Center, avoid another bond issue that might encounter yet more technicalities in debt-averse Oklahoma, and reduce the city’s operating expenses by combining facilities.

The Red Cross headquarters moved out of the Civic Center’s north wing, which was opened up into one big room, becoming the library’s new home in September 1927. The school system wound up taking over the old Carnegie library, making it an administrative building until 1974, when it was sold off to become law offices.

By the summer of 1930, the library was outgrowing its new quarters, and in March 1931 it was operating branches at three of the schools and the hospital. In May 1931, it opened another branch near the West Side Park that was open on one morning and another afternoon each week.

However, despite heavy patronage, a bond issue to enlarge the library was defeated in 1940, and it was embroiled in controversy in 1950 when Ruth Brown, the librarian since 1919, was fired for her support of Civil Rights, under the pretense of her being a Communist subversive.

The town continued to grow, but the library was wholly inadequate. Bond elections in 1957 and 1959 failed.

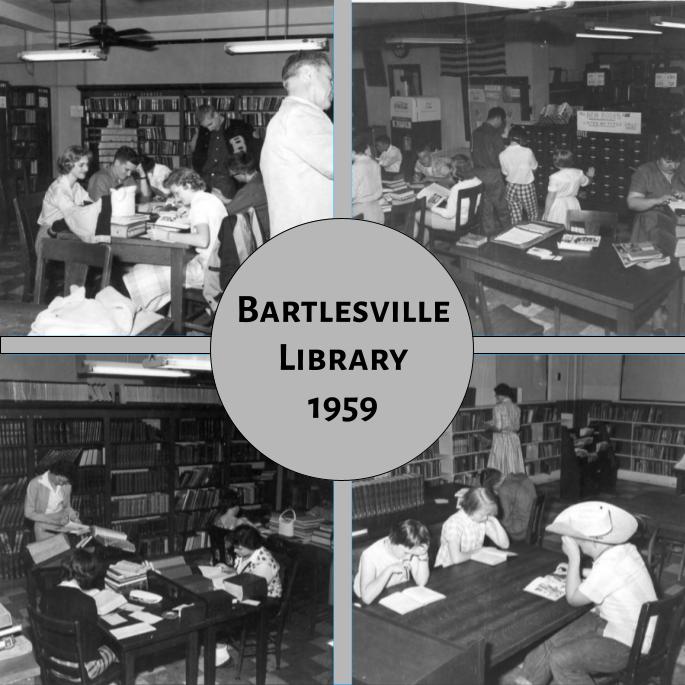

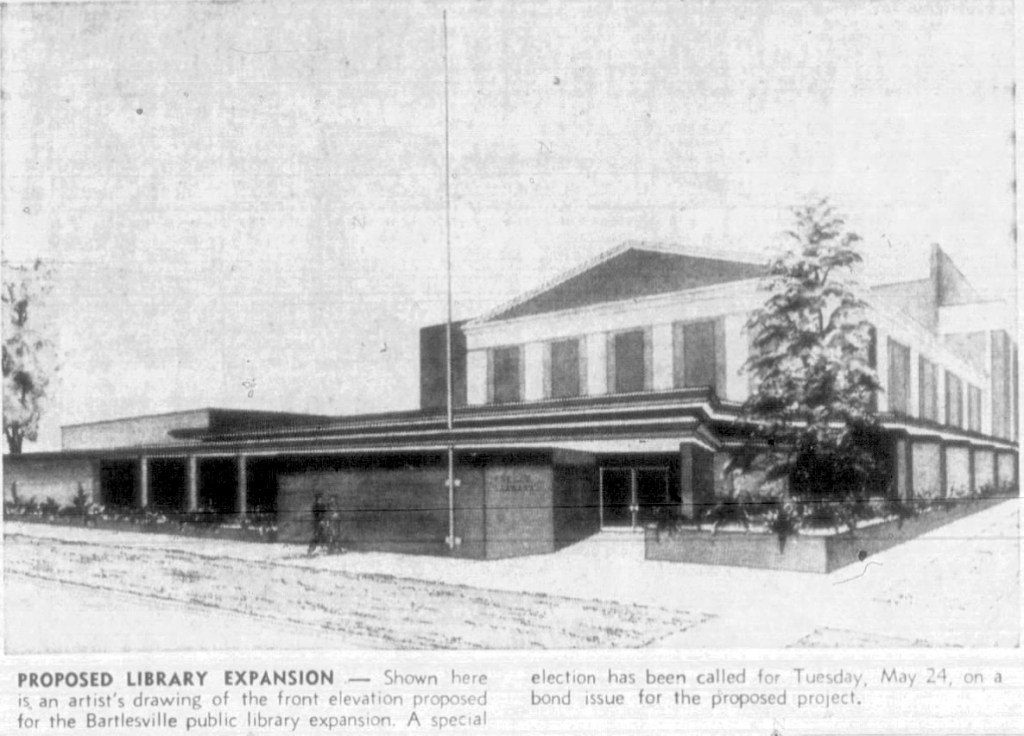

In 1960, 59% of the voters, by 1,873 to 1,275, finally approved a library bond issue. The resulting modernist appendage tripled the library’s size, but it in no way complemented the architecture of the older structure.

In 1989, Bartlesville still depended on that aging 1960 wraparound on the north end of a 1922 building that had been mostly abandoned for about a dozen years.

The Controversy I Moved Into

Just a block or so to the east of the old Civic Center was the mothership, the Bartlesville Community Center. Designed by the son-in-law of Frank Lloyd Wright, it featured an impressive 1,700-seat performing arts hall accompanied by a large events room, art display gallery, and basement drama room. The facility was built from 1979 to early 1982 for $13 million, funded by private and corporate donations and a three-year penny sales tax. Space for it was created by razing the city’s first brick school building, Garfield, and the wounds lingered.

The city had abandoned much of the Civic Center in 1976, amidst competing claims about its structural integrity. The new Community Center reflected how Phillips Petroleum, a Fortune 500 company, was then still headquartered in little Bartlesville. An oil boom meant the company was expanding rapidly, and it wanted better amenities to help it attract and retain workers.

However, oil booms are often followed by busts. Phillips peaked in the early 1980s with over 9,000 workers in town but then came decades of downsizing. In 1985, amidst the oil bust, a 3/4-cent sales tax proposal to demolish the Civic Center and build a new library failed with only 36% approval: 3,107 for to 5,455 against. By 1989, Phillips employment in Bartlesville had declined by almost 40%, to about 5,400 workers.

Phillips was still so dominant at the time that when I rented an apartment at The Village, they mistakenly assumed I was a young Phillips hire. They asked me what “grade” I was, and I thought they meant what grades I’d be teaching at Bartlesville High School, so I answered, “Both 11 and 12.” They were puzzled by that response, and it turned out that they were asking about my Phillips employment classification. It was an introduction to life in what was still very much a “company town”.

No Attachments

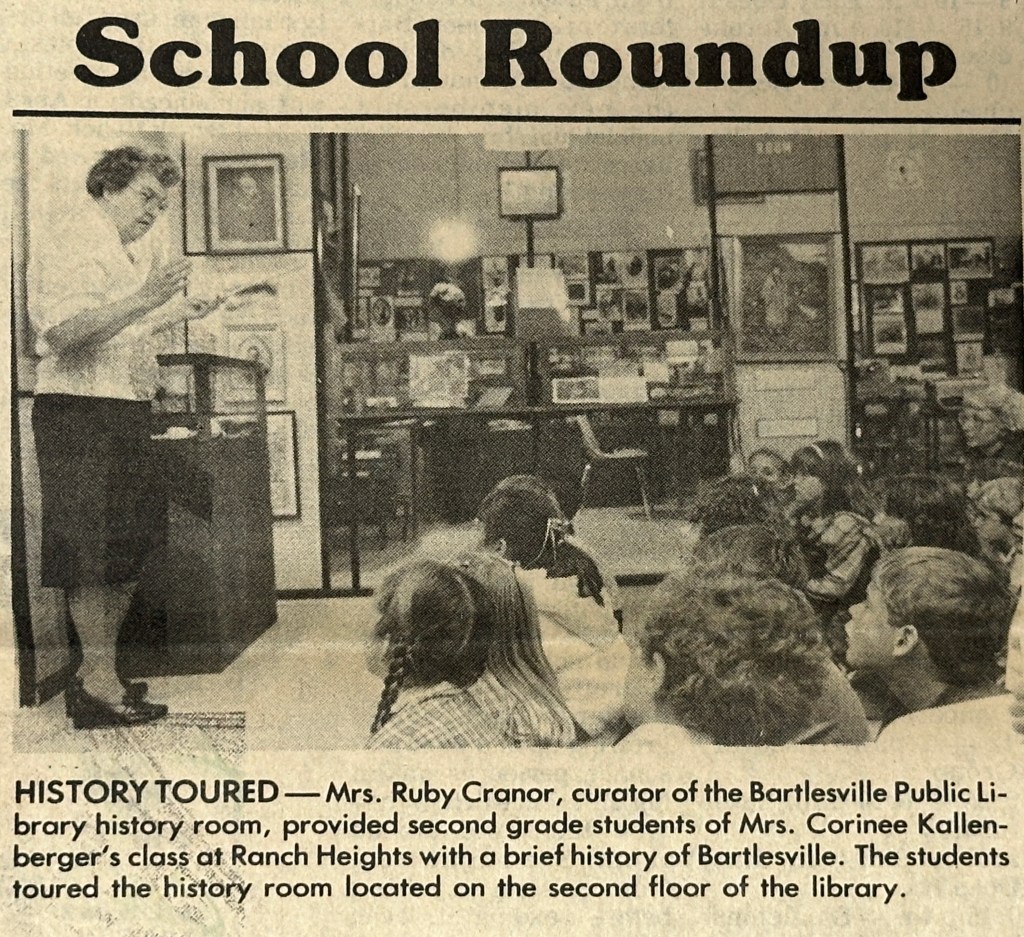

As an outsider moving into town, I explored the library, but considered it quite lackluster amidst the town’s striking amenities. Sure, it was 70% larger than the tiny branch library I grew up with in OKC, and it did feature a history room, over a decade before the Bartlesville Area History Museum would come about.

However, to my eyes, having never been in the Civic Center in its heyday and only seeing it in its partially abandoned state, it was an obsolete eyesore that served no purpose save for an old mismatched library retrofitted into its north end. It made perfect sense to me, having no nostalgia for the structures, that the city should tear it down and build a larger and much more modern library in its place.

Well, some did not agree, because they had been captured by the nostalgia trap, which doesn’t care about economic viability or functional suitability. A retired Phillips employee in his early 60s, not much older than I am while composing this post, organized a 25-member Concerned Citizens of the Bartlesville Area. They collected 1,409 signatures on a petition against demolishing the old Civic Center, demanding a citywide vote on the issue. I did not find a sensible or economically viable proposal from them on what to do with the obsolete and redundant facility, just a demand that it not be destroyed. It would have been very expensive to renovate the entire old Civic Center into an adequate new library, and the result would have been compromised by the mismatch with its original design.

Thus, on September 12, 1989, I participated in my first Bartlesville election, voting Yes on a $2.5 million bond issue to demolish the Civic Center and construct a new library in its place. It passed with 56% approval: 5,161 to 4,061.

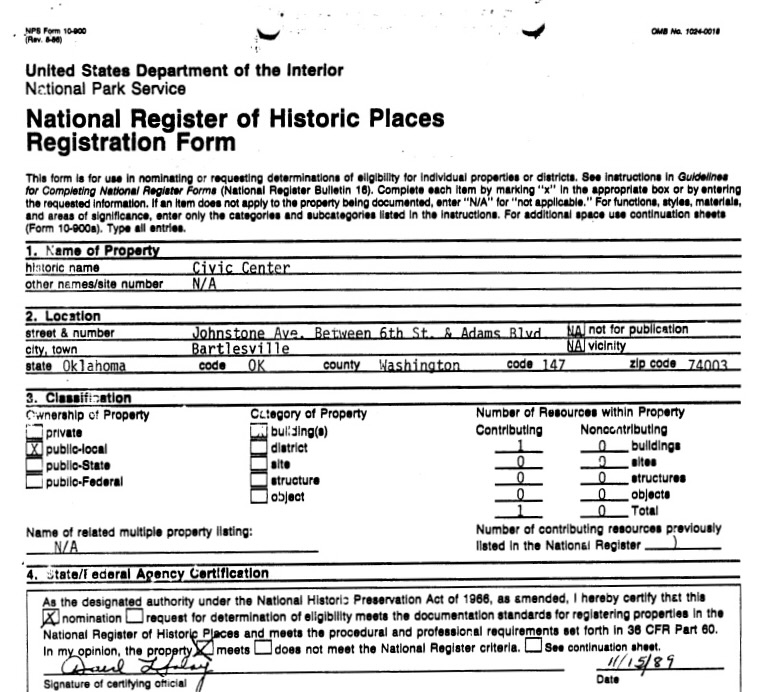

The fellow opposing the demolition finally succeeded in getting the old Civic Center on the National Register of Historic Places, but that recognition didn’t come until November 1989, months after the vote. Contrary to popular belief, such recognition merely encourages preservation by making some properties eligible for rehabilitation tax credits. It does nothing to prevent owners from remodeling, selling, or demolishing a listed property.

I learned another lesson about Bartlesville politics when another citizen took the city to court, trying to invalidate the election. I, for one, did not take kindly to someone trying to override my vote. I’ve disagreed with the majority in many an election, but I was taught to adapt to, rather than try to subvert, majority rule. The district court ruled against the complaint, but then he appealed to the Oklahoma Supreme Court on various technical grounds. They affirmed the district court in April 1990, and the Civic Center was demolished in the summer of 1990.

I was very glad to see the library temporarily move into what appeared to be a former T.G.&Y. and for the Civic Center to come down, because I had no experience with nor nostalgia for that old building, while I was genuinely excited for a new library slated to replace it. If I had grown up in Bartlesville, I would still have supported the project, but the destruction would have been much more impactful.

Sound familiar? 35 years later, I get to watch OKC demolish a facility that hosted major events in my life. I couldn’t care less about sports, so the new arena that will replace the old convention center will do little for me, but it will serve many sports fans who are eagerly awaiting the new venue. The tables have been turned!

The Third Bartlesville Library

Back in Bartlesville 35 years ago, the library campaign raised another $1.5 million in private donations to augment the bond election, and the project broke ground in February 1991 and the new library opened in January 1992. It was the last project of architect Thomas McCrory, who would soon sell his business to Scott Ambler, who had been heavily involved in the design of the new building. In 2017, Joseph Evans, once one of my physics students at Bartlesville High School, who worked on major additions to that campus in 2015, became the President of Ambler Architects. Now he owns the firm, which in 2025 was renamed HorizonLine Architecture and Interiors. How time flies.

I’ve always appreciated the “new” library, which is still a beautiful and functional space, continuing to adapt to changing times. I am grateful that the nostalgia trap did not prevent its construction.

Avoiding the Trap

The nostalgia trap is open and waiting, but it shan’t capture me. I’m impacted, but not upset, that what I knew as the Myriad is going away. I know that it wouldn’t make any sense for the city to preserve it, since a $288 million replacement opened in 2021. The old convention center had plenty of shortcomings throughout its half-century of existence, and the new arena that will replace it was approved by the voters.

Yes, there’s already an indoor arena just to the south, built in 2002 for $89 million. Back in 2008, the city raised over $103 million to improve that facility for the relocated Seattle Supersonics NBA team, which became the Oklahoma City Thunder. (My lack of interest in sports was evident when people starting talking about the team back then: at first I thought they were discussing some sort of weather event.) Now OKC is raising a billion dollars to keep the Thunder playing there for a quarter-century, and I presume the 2002 arena will be redundant once the new one opens in 2029.

Given the significance of the Myriad in my own life, I could decry its destruction. Given the mismatch in interests, I might be tempted to consider a billion-dollar arena a waste of resources. However, I won’t take the bait. I’ll continue to enjoy the public library in Bartlesville, and no doubt many will soon enjoy OKC’s new arena.

The past deserves honor, but not necessarily publicly funded preservation. Oklahoma has always limited its public investments, meaning we must often destroy in order to create. The vote was taken. So be it.

Granger, I’ve seen some of your posts in the past and wondered about your background in Bartlesville. I have to say, I’m very impressed by your research for someone who didn’t grow up in “B’ville.”

I remember the old Civic Center and watching my parents rehearse the Little Theater in the basement of the Civic Center and then watching them perform. I also saw some performances over the years. I twice saw the cowboy Western star Tim McCoy bring his troupe to perform there (my Dad was friends with Tim). If I remember correctly, Gary Lewis and the Playboys and the Cowsills (or a couple of them) played their too.

As you mentioned, the story I heard of it’s demise was that a faction wanted a new Civic Center and all of a sudden and conveniently the Civic Center was condemned. It sat empty and unused for two or three years or more, before a new Civic Center was approved.

Thanks; my father was born in Dewey in 1925, and he lived there until he was 11, and my double first cousin once removed was area historian Edgar Weston, so there is some family history in the area. One thing that has always struck me is a paucity of photographs thus far of the interior of the old Civic Center. I’ve seen a handful of shots of performers on the stage, but none of the seating, the stairways, balcony, the offices on the south end, and the like. It had been closed for a dozen years when I moved to town, so all I could see was the exterior and the library on the north end.