Our stay in Lawrence during Thanksgiving Break 2025 allowed me to explore some family history, since my father was a KU Jayhawk in the late 1940s. Dad had completed a freshman year of studies at Independence Junior College before being inducted into the U.S. Army in August 1943 at Ft. Leavenworth. He had been born blind in one eye, but he still managed to qualify for a marksmanship badge, and Dad served as a military policeman in Denver and then set up water purification plants as part of an engineering battalion in Germany and later the Philippines. He was honorably discharged in April 1946 and moved back home to Independence, Kansas.

In September 1946, Dad enrolled at KU to study engineering, funded by the G.I. Bill, which he recalled as paying some toward his tuition and books and providing a monthly stipend. Dad hitched a ride for the 140-mile trip to Lawrence, where he enrolled in chemical engineering.

Car Trouble

Dad lived in a boarding house during that sophomore year and quickly realized he would need a car. He bought a 1930 black Chevy coupe, figuring out that its stalling was caused by a silk rag that had fallen into the gas tank. When a valve shot through the engine block, Dad had a shadetree mechanic replace it and braze shut the hole for $35. He drove the problematic vehicle down to Independence, borrowed $435 from his father, and bought a black 1929 Model A coupe with cream-colored wire wheels. Although his second car was a year older, it was far more reliable.

Dad recalled how the streets leading from downtown Lawrence to the university campus would become quite icy, and once while driving up Mt. Oread the car did a 180-degree about face and he went back down the hill, thankfully with no damage. I had a similar incident forty years later while driving on icy US 77 into Norman on my way to the University of Oklahoma. My rear-wheel drive 1981 Toyota Celica Supra suddenly began a complete 360-degree spin. I followed the advice from driver’s education, turning into the skid and pumping the brakes, only to arrive back in place in my lane, again facing forward. Motorists around me had paused, their faces frozen in alarm, but there were no impacts, and I too was able to proceed with no damage. I was lucky, and I stuck with the decision I made that morning that every subsequent car I bought would feature front-wheel drive.

Apartment Living in Lawrence

Dad got married in December 1946 to his first wife. They found their first apartment, a furnished one with a few steps up to an entryway and a few steps down to a bathroom. However, when they turned on the water for the kitchen sink, there was an odd sound as it drained. They opened the cabinet to find the sink drained into a bucket, which had to be carried out the front door, down the steps to the sidewalk, down more steps to the basement bathroom, and then dumped.

Needless to say, they looked for better accommodations. Downtown, just across the alley from the back wall of the Granada Theater, was a two-story red brick building that had once been a carriage house on the alley behind a house that had been reduced to just a foundation. The carriage house was split into four apartments, with the landlady in the front downstairs. Dad and his bride rented an upstairs unit, which was reached by a wooden stairway from the alley up to an enclosed landing, which had an ice box with two doors to the two upstairs apartments, which shared the ice box and a common bathroom.

One incident my father recalled was when he smelled smoke coming from down below. He realized it was coming from the landlady’s apartment. Banging the door yielded no response, but Dad knew she kept a hideout key in a small shed at the front of the house. He got the key, opened the door, and discovered a pan had been left on a lighted burner on the gas stove and had burned dry its contents. Thankfully the fire had not spread, so he turned off the burner, aired the house out, left a note, locked the door, and replaced the key.

When the landlady returned, “Here she came, not to thank me for saving her home but to ask me how I knew she had a hideout key in the shed out front. I don’t remember how I knew, but I had probably observed her retrieving it at some time. Bless her heart!”

While Wendy and I were in Lawrence, I checked the alleyway behind the Granada Theater. I could see the theater’s back wall against the alley, as my father had described. However, there was just an empty parking lot beyond. The carriage house, like the main home it had been built for, was long gone.

After completing his sophomore year, Dad switched to studying petroleum engineering. He managed to complete the degree in his three years at KU, graduating in the spring of 1949. Dad would spend 35 years in the petroleum industry, catching peak years of oil and gas activity.

Dad’s College Jobs

To make ends meet, Dad took several part-time jobs to supplement his G.I. stipend, including sanding the floors at one of the Lawrence school gymnasiums.

Dad later wrote:

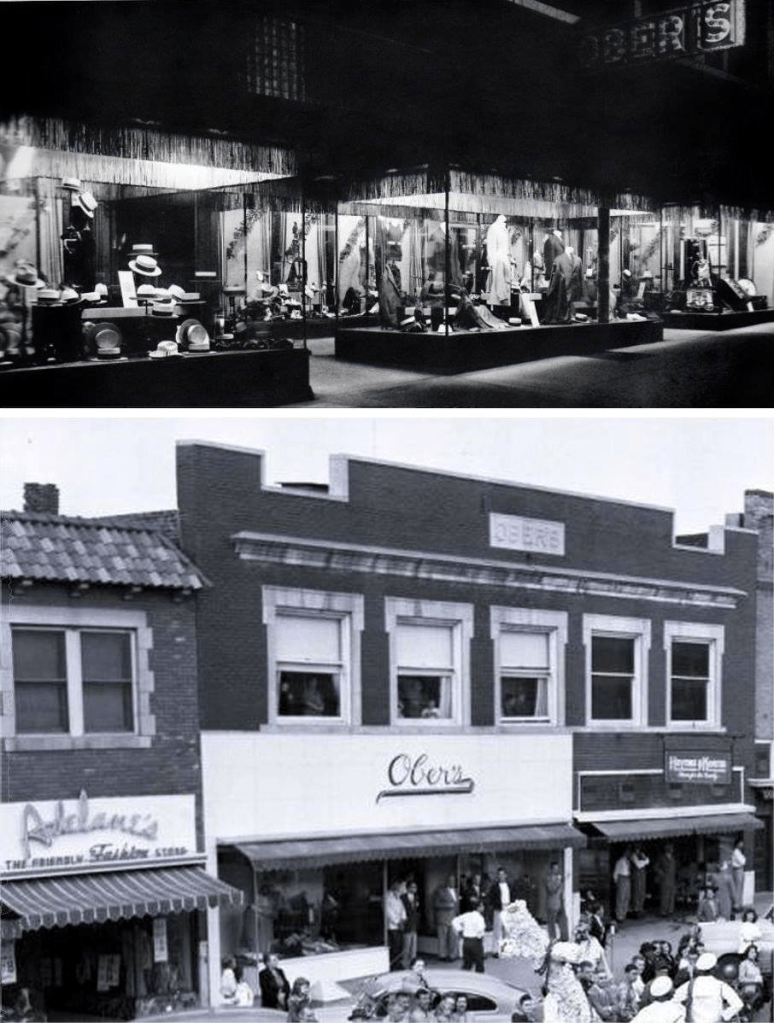

My best job, and one I kept from year to year, was presser of alterations at Oberʹs Menʹs Shop, the swankiest menʹs shop in downtown Lawrence. There was a balcony affair above and at the back of the store which served as an alterations and pressing room. Up there, high above the sales floor, a little lady seamstress did all the alterations of suits, pants, jackets, etc. sold in the store. After she was through with a garment she would hang it up to be pressed. I would come in and steam press the alterations she had done on a given day, or come in on Saturday and press all she had done over a period of a few days.

I was paid 43¢ an hour and was given a ten or fifteen percent discount on anything that I purchased from the store. I donʹt remember the exact percentage because I was never able to afford anything that they had for sale, not even a necktie. I recall being up there every Saturday afternoon pressing away and wishing I was out watching KUʹs home football games. All the time that I was at KU the University of Oklahoma team always beat our Kansas team. I contended that the reason the Oklahoma Sooners always beat our Jayhawkers was that they had their own football to practice with.

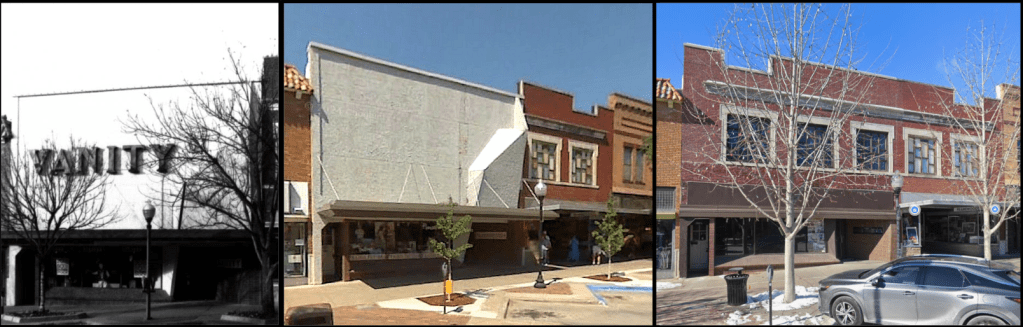

Henry “Bert” Buell Ober had purchased the store from Abe Levy way back in 1896. By the time my father worked there, Ober’s had downsized into the southern part of its building, and eventually the upstairs area was used to sell Boy Scouts apparel. I was unable to determine when the store closed, but in the 1980s or 1990s the south part of the building was “modernized” with a hideous new façade, causing the building to be designated as “non-contributing” in the historic downtown’s listings in the National Register of Historic Places. Thankfully, sometime between 2019-2021 the original brick design was restored. I was gratified that anything recognizable remained in downtown Lawrence that my father had mentioned from his time there over three-quarters of a century earlier.

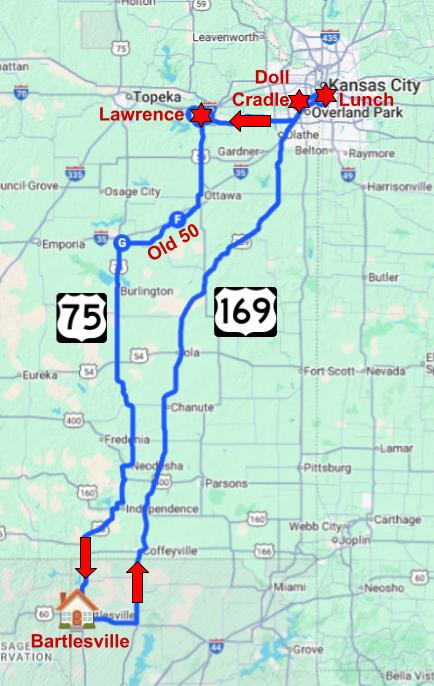

Back to B’ville

On our third day in Lawrence, we packed up and drove over the west side of town for breakfast at The Big Biscuit. Then we drove south on US 59 to Ottawa. We could have taken Interstate 35 southwest to US 75, which leads through Bartlesville 130 miles to the south.

However, I wasn’t in the mood for that, and opted to divert around the western edge of Ottawa and take Old Highway 50 to US 75.

What would have been a 28-mile 24-minute drive thus became a 29-mile 34-minute drive along a nearly deserted highway through the little towns of Homewood, Williamsburg, and Agricola.

Charles Kuralt did On the Road segments across a million miles for a quarter-century, riding in a motor home with a small crew, avoiding interstates in favor of the nation’s back roads in search of America’s people and their doings. I’d catch one from time to time on CBS. Kuralt once remarked, “Thanks to the Interstate Highway System, it is now possible to travel across the country from coast to coast without seeing anything.”

I enjoyed that mild detour, but soon we were on familiar US 75. After I moved to Bartlesville and first began traveling to Kansas City, I took 75, but it was so deadly dull that I switched to US 169, which is mildly, quite mildly, more interesting. We could have driven south from Ottawa to catch 169 at Garnett. Rather than repeat ourselves, however, I stuck with 75 through Burlington, Yates Center, past Buffalo and Altoona, turning to track through Neodesha.

US 75 briefly merges with US 400 south of there, and I often miss the turnoff where 75 resumes its dedicated track past Sycamore. Sure enough, I missed the turnoff again, having to make a U-turn to try again. Then we zipped through Independence, familiar to me from many childhood visits with relatives there. Having shamed myself at missing the earlier turnoff, I sought redemption by bypassing town via a diversion west on Taylor Road to then turn south on Peter Pan and then rejoining 75.

Peter Pan & Braums

As a kid, I was amused that a section road near Independence was named Peter Pan. It was named for one of the Peter Pan Ice Cream Stores. In 1933, Henry H. Braum started a butter processing plant in Emporia, and in 1952 one of his sons, Bill, developed a chain of retail ice cream stores across Kansas.

In 1967, the 61 Peter Pan Ice Cream Stores were sold off, but the sale did not include the Braum Dairy or its processing plant. The sale terms forbade the Braums from selling ice cream in Kansas for a decade, and Bill moved the business to Oklahoma City. The first Braum’s Ice Cream & Dairy Store opened in 1968 a few blocks from where I lived from 1978 to 1984. Now the family owns and operates over 300 stores across Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas. The Peter Pan store in Independence is long gone, but they do have a Braum’s!

But why did Bill Braum call his first stores Peter Pan? Well, in Emporia there is a Peter Pan Park. It originated when a young girl, Mary White, died of injuries from a horse-back ride. Her father wrote an editorial about her life and funeral, and referred to his daughter as a “Peter Pan” girl who did not want to grow up. The article yielded contributions to the family, which they used to build a park.

Little House on the Prairie

Just 11 miles southwest of Peter Pan Road in Independence, just a mile off US 75, is the site of the actual Little House on the Prairie, where Laura Ingalls lived in 1869-1870. Laura’s father had moved the family there from Wisconsin, thinking that the Kansas area would soon be up for settlement. However, their homestead was on the Osage Indian reservation, and they returned to Wisconsin.

Little House on the Prairie is the third book in the series of eight novels that Laura Ingalls Wilder published from 1932 to 1943. The first one will enter the public domain in 2027, and the third in 2030.

There is a museum on the property, open Thursdays-Saturdays from March through October. It has a replica of the Ingalls family cabin, an old post office, and a one-room schoolhouse. However, we’ve been there, done that, and anyways, the museum isn’t open in November. So we continued on south through Caney, Copan, and Dewey to return home.

We enjoyed visiting Lawrence, and I expect that Wendy and I might do a similar trip someday, visiting Kansas City and staying overnight at the TownePlace Suites by Marriott in downtown Lawrence. However, I think we’ll again want to time that to match up with a holiday break…we aren’t college kids anymore, by a long shot.

Wow, nice work on this post! How on earth did you get so much info about your Father? My Dad, roughly the same age, was reticent about sharing info, though if you asked him specific questions he would answer them. I would have had to ask him a million questions to obtain the info you shared!!

Dad enjoyed writing a couple of memoirs, so I am fortunate in being able to draw upon those.