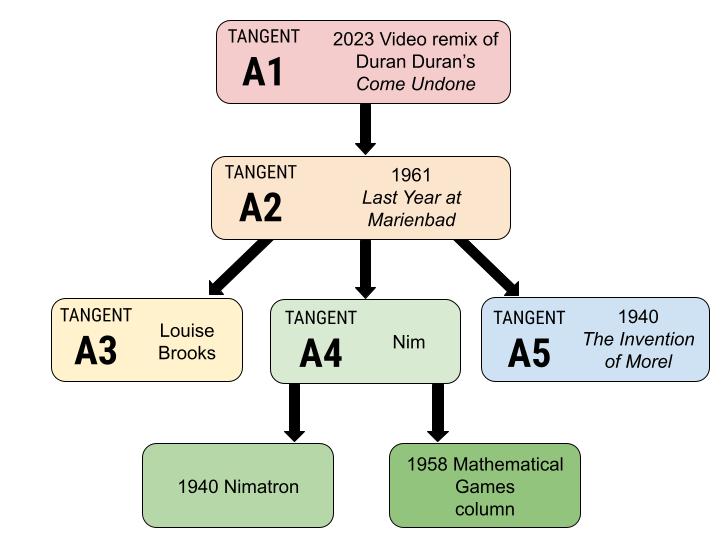

This is the second of five snowed-in posts, illustrating the pathways I sometimes pursue due to my avid curiosity. This Tangent began with a video remix of an old song by Duran Duran, which had inserts from a French New Wave film from 1961.

Here’s the video that instigated this Tangent:

French New Wave

In my younger days, I would occasionally skim issues of the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma at public libraries, although my French was limited to a few weeks in fifth grade and its descent from Latin, which I studied for a few years in high school and college. Thus I thought of the magazine’s title as Cashiers rather than Cahiers since I was unfamiliar with the French word for notebooks. I enjoyed seeing retrospectives on the work of auteurs like Truffaut, Godard, and Demy, and I have seen Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 of 1966, Godard’s Alphaville of 1965, and I have a Blu-Ray of Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg of 1964 that I’m saving as a post-retirement treat. The sumptuous yet strange visuals in the music video reminded me of that era when French directors rejected traditional filmmaking conventions.

Cahiers promoted the work of “Right Bank” filmmakers, who were primarily film critics with cinephile backgrounds. However, there were also slightly older “Left Bank” filmmakers who often came from literary, documentary, or other arts backgrounds. While Godard and Truffaut might focus on formal experimentation like jump cuts, the Left Bank integrated other art forms and had more overtly political, literary, and intellectual themes. The latter were associated with the intellectual and bohemian “Rive Gauche” or “Left Bank” of Paris.

Last Year at Marienbad

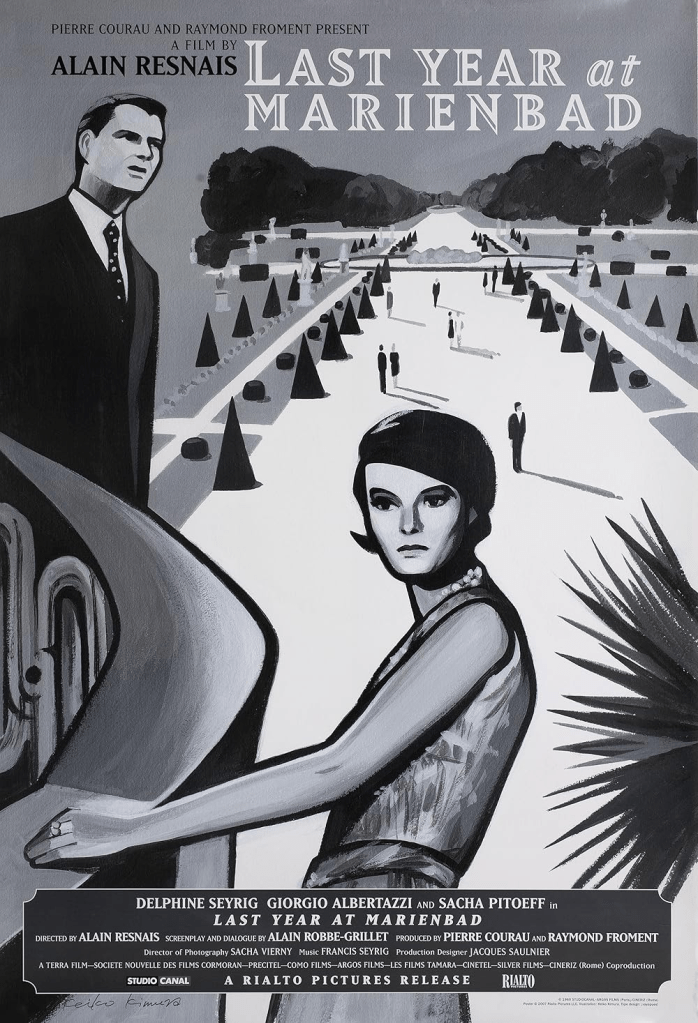

A Google Lens search identified the female protagonist as actress Delphine Seyrig in director Alain Resnais’ 1961 film L’Année dernière à Marienbad or Last Year at Marienbad. So the video was remixing with a Left Bank film. I was familiar with that group’s La Jetée by Chris Marker, which inspired one of my favorite films, 12 Monkeys, but I’d never heard of Marienbad.

Coco Chanel

The beautiful gowns that Seyrig wore in the film were immediately arresting. I presumed they were by a French designer, but I was surprised to learn that Coco Chanel was responsible, albeit uncredited in the film. You see, Chanel had met Hollywood mogul Samuel Goldwyn at Monte Carlo way back in 1931, and he had paid her a million dollars to come to Hollywood a couple of times per year to design costumes for his films. Chanel came to dislike the culture of the film world and only worked on a few films there, declaring, “Hollywood is the capital of bad taste … and it is vulgar.”

Hence I didn’t expect to see her designing costumes for a Left Bank film decades later. However, Director Alain Resnais admired Chanel’s timeless style and asked her to do the film’s costumes when she was 77 years old. Resnais and screenwriter Alain Robbe-Grillet wanted 1920s glamour blended with 1960s modernity, and Chanel’s clean lines, little black dresses, and use of chiffon and tulle were well-suited to the film’s black-and-white cinematography.

I should note that Coco Chanel, like many influencers, had her flaws, as documented by YouTube fashion historian Nicole Rudoolph, MA.

The Alains

Writer Alain Robbe-Grillet and director Alain Resnais collaborated on the film, with Robbe-Grillet writing a detailed screenplay that went beyond dialogue, gestures, and décor to include the placement and movement of the camera and the sequencing of shots.

Robbe-Grillet’s preface to the story shared: “The whole film is in fact the story of a persuasion, what is involved is a reality that the hero creates by his own vision, through his own words. [. . .] It all takes place in a luxury hotel, a sort of international palace.[. . .] An unnamed man goes from room to room [. . .], walks down interminable corridors. [. . .] His glance moves from one nameless face to another nameless face. But it always comes back to one face, that of a certain young woman. [. . .] To her, then, he offers [. . .] a past, a future, freedom. He tells her that they have already met, a year ago, that they became lovers, that he has returned now to this rendezvous which she herself had made, and that he will take her away with him.”

“She does not wish to leave the other man [. . .] who watches over her and who is perhaps her husband. But the story told by the stranger becomes more and more real; irresistibly, it becomes more and more true. The present and the past have, besides, finally become fused, while the growing tension among the three protagonists creates in the mind of the heroine tragic phantasms: rape, murder, suicide. . . .”

Resnais filmed that script with great fidelity, although there are inevitable differences. The most notable of those is that Resnais was not interested in filming the rape, instead emphasizing the hero’s rejection of that scenario, agitatedly reformulating it into a willing and welcome embrace. However, in the repeated overexposed tracking shots moving toward the smiling woman of that reformulation, her strange smile and the tilting of her head are simultaneously comical and disturbing — deliberate off-putting choices.

The conclusion is a sudden linear narrative of the woman accepting the hero’s narrative, finally being willing to “go away with him, toward something […], love, poetry, freedom … or, perhaps, death.”

The Critics

I resisted watching Last Year at Marienbad for some time, even though it was clearly gorgeous, because I fully expected it to be difficult, obscurantist, and pretentious given its Left Bank origin. I dislike and often disagree with New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael, but her caustic take on the film no doubt has elements of truth:

Here we are, back at the no-fun party with non-people, in what is described to us as an “enormous, luxurious, baroque, lugubrious hotel — where corridors succeed endless corridors.” I can scarcely quote even that much of the thick malted prose without wanting to interject — “Oh, come off it.” The mood is set by climaxes of organ music and this distended narration; it’s all solemn and expectant — like High Mass. But then you hear the heroine’s thin little voice, and the reiterated questions and answers, and you feel you shouldn’t giggle at High Mass, even if it’s turning into a game of Idiot’s Delight.

However, my tastes often aligned with Roger Ebert, and he recalled standing in the rain in college to see the film, and remembered it more fondly.

Yes, it’s easy to smile at Alain Resnais’ 1961 film, which inspired so much satire and yet made such a lasting impression. Incredible to think that students actually did stand in the rain to be baffled by it, and then to argue for hours about its meaning–even though the director claimed it had none.

…

Viewing the film again, I expected to have a cerebral experience, to see a film more fun to talk about than to watch. What I was not prepared for was the voluptuous quality of “Marienbad,” its command of tone and mood, its hypnotic way of drawing us into its puzzle, its austere visual beauty. Yes, it involves a story that remains a mystery, even to the characters themselves. But one would not want to know the answer to this mystery. Storybooks with happy endings are for children. Adults know that stories keep on unfolding, repeating, turning back on themselves, on and on until that end that no story can evade.

Ebert recalled sitting over coffee in the student union with Gunther Marx, a professor of German, after seeing the film for the first time. Marx told him, “It is a working out of the anthropological archetypes of Claude Levi-Strauss. You have the lover, the loved one, and the authority figure. The movie proposes that the lovers had an affair, that they didn’t, that they met before, that they didn’t, that the authority figure knew it, that he didn’t, that he killed her, that he didn’t. Any questions?”

I could hug Roger for his addition: “I sipped my coffee and nodded thoughtfully. This was deep. I never subsequently read a single word by Levi-Strauss, but you see I have not forgotten the name. I have no idea if Marx was right. The idea, I think, is that life is like this movie: No matter how many theories you apply to it, life presses on indifferently toward its own inscrutable ends. The fun is in asking questions. Answers are a form of defeat.”

You are so difficult!

Difficult films are hit-and-miss for me. I like much of David Lynch’s work, including the nonlinear Lost Highway and the puzzle box of Mulholland Drive, but I couldn’t make it through Inland Empire. I tried to watch Terence Malick’s Tree of Life, but it desperately needed pruning.

There are meta-narrative films, however, that I adore, such as Being John Malkovich, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and Stranger than Fiction. For me, French New Wave films are not in their league and can be particularly tiresome. I suspect they might be more enjoyable with RiffTrax comedic commentaries than in their original forms.

So, given my reluctance, how did I come to watch Last Year at Marienbad? Well, several months ago I purchased a new 4K HDR release of Danger: Diabolik from Kino Lorber, which had been the subject of an episode of the Perf Damage podcast with Charlotte Barker, Paramount’s Director of Film Restoration, and her husband, Adam. I might guess that influenced the algorithms crafting my online experiences to promote Kino Lorber’s products on Amazon Prime. Thus, when I opened the Prime Video app on my iPad to seek entertainment, it offered up the Kino Film Collection. A bit of idle side-scrolling then brought the thumbnail of the film into view. I could watch it for free, so long as I remembered to cancel a 7-day free trial of the sub-service. Hmmm…why not?

So I watched this difficult and beautiful film in bed on a little 10.9″ screen at about 2K resolution while wearing a bone conduction headset with mediocre sound quality. How fitting for these times, and thank goodness for subtitles.

The film was indeed exasperating, fascinating, foolish, disturbing. There was obviously intercutting in the editing between multiple scenes, without clear signals of past versus present except occasional revealing dialogue. Deliberate mismatches of dialogue and visual descriptions accompanied shifting, inconsistent realities that reminded me of several of David Lynch’s later films. I didn’t find the film profound, as it seemed mostly only surviving surfaces of a plot that had been eviscerated, but it tickled my curiosity in multiple ways.

Firstly, what was so familiar about Delphine Seyrig’s appearance? The film’s obvious choices to have many characters arranged in motionless and stilted tableaus, the dated play-within-the-film, and the cinematography all seemed to pay homage to silent films. Sure enough, director Resnais had unsuccessfully tried to get Kodak to supply old-fashioned film stock that would bloom and halo like in the old silents, and he wanted Seyrig’s appearance and manner to resemble that of Louise Brooks in 1929’s Pandora’s Box. Thus we turn to follow Tangent A3.