Traditional teacher preparation has cratered in Oklahoma, which saddens me since I and the 2,663 students I taught from 1989 to 2017 benefited so much from my choice to major in education back in 1986. When I enrolled at the University of Oklahoma (OU) in 1984, I originally majored in Engineering Physics. Two years later, right after being named an Outstanding Sophomore in the program but having become disillusioned with that major, I applied to switch to Science Education, feeling the call to teach high school physics.

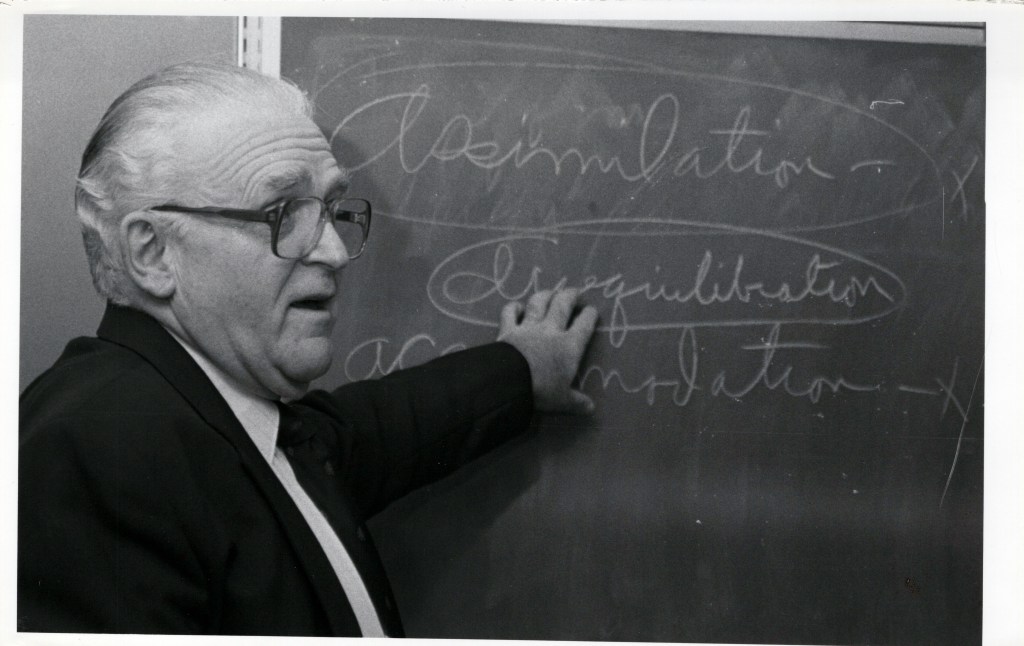

Dr. John Renner, an outstanding leader in science education and the learning cycle, interviewed me. I thought he would be thrilled to have me, given my academic prowess, but after reviewing my transcript he tried to turn me away.

He said I was too bright to be teaching high school science, that full-time physics positions in Oklahoma high schools were quite rare, and that I should stick with Engineering Physics. “Get your degree and then teach physics at a university, not a high school.”

I’ve always been stubborn, and I insisted that I wanted to train to teach high school physics. Renner eventually caved, providing me with the opportunity to develop my pedagogical skills. The university also protected me from being too narrow in my teaching specialization by requiring me to expand my science courses.

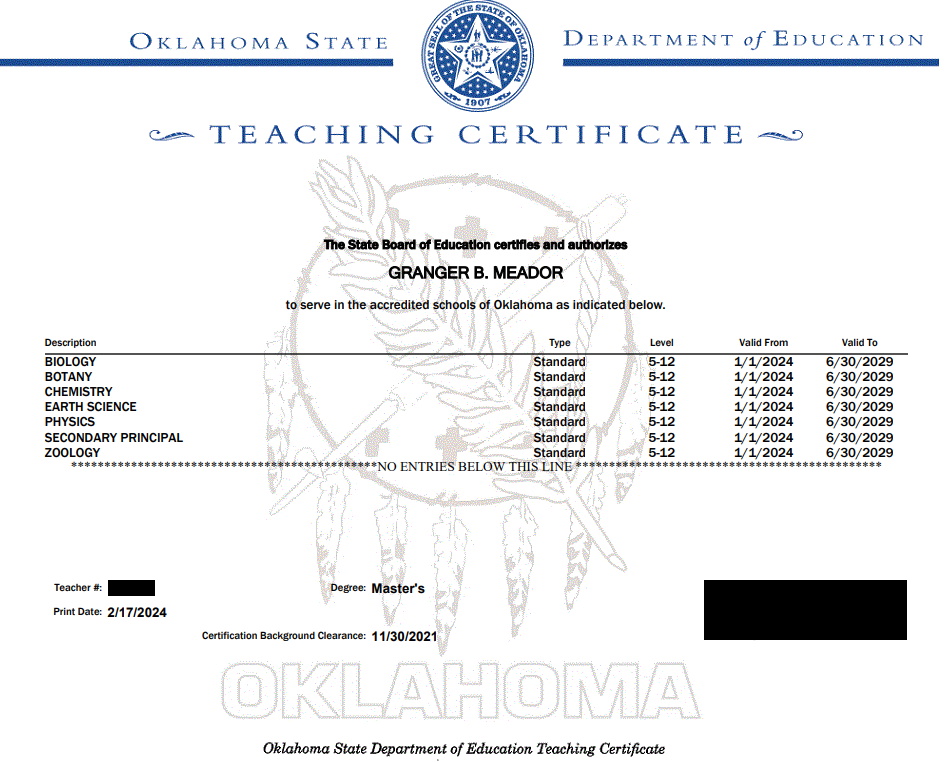

My original major demanded plenty of physics, engineering, and some electronics plus one course in chemistry. My new major required additional credits in astronomy, botany, psychology, geology, zoology, ecology, geography, and physiology. That allowed me to earn certifications to teach Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Botany, Zoology, and Earth Science in an era when you had to have a certain number of hours in each subject as well as pass a certification test in it. That way I would be marketable to a much larger selection of school districts.

However, in my job search after graduation, I was equally stubborn about wanting to only teach physics. I turned down offers to teach various non-physics subjects at three different districts before I snagged the full-time physics position in Bartlesville, which I held for 28 years before transitioning into administration.

As it turned out, I never taught using my other science certifications, although I have zero regrets about the varied coursework. I loved the various sciences, and being certified in the other subjects did help me in my 20 years of chairing the science department across grades 6-12, since I had a background in what my colleagues were doing.

My switch in majors had me earn 20 credits in education courses, plus another 10 as a student teacher in Bill Fix’s physics classes at Norman High. That undergraduate education coursework set me up for success in my chosen career. A course in Educational Psychology was especially helpful, along with the Piagetian theory and practicums in teaching science, using materials by Dr. Renner and direct guidance from Dr. Edmund Marek. Spending a full semester with Mr. Fix using the learning cycle in physics, first observing and then gradually taking over his classes, set me up for success when I had my own courses a year later.

Even though switching majors meant spending an extra semester in school plus some summer school classes, without scholarship support, that worked in my favor since it meant that I did my student teaching in the first semester of the school year. I was able to observe firsthand how a master teacher built rapport and established norms with groups of students. Because I graduated in December 1988, I spent the early months of 1989 substitute teaching in the Putnam City school district I had attended in grades 1-12. That too was helpful in that I was temporarily embedded in multiple high schools and a variety of subjects outside my expertise. That was a crash course in classroom management, often with students in mandatory courses who were far less motivated than students in an advanced elective science. It also meant I was 23 years of age, rather than 22, when I started teaching in Bartlesville, and I’m sure that extra year of maturing helped somewhat.

Unfortunately, that sort of education coursework and practical preparation is what many now applying to teach in our public schools lack, since they certify through alternative means. I am an expert in pedagogy, but that expertise is often undervalued by people who naively think that subject expertise is all that matters.

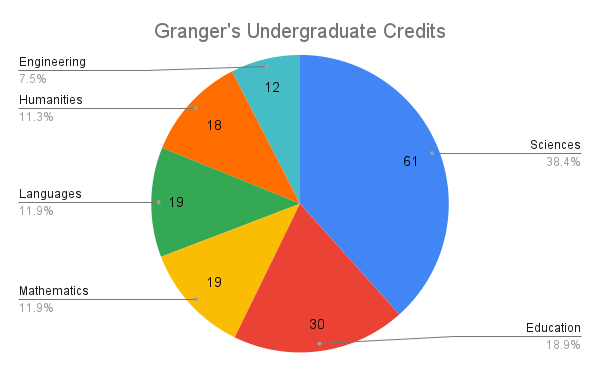

Here is the breakdown of my 159 undergraduate credits, which provided me with a solid background in both my subject and the art of teaching:

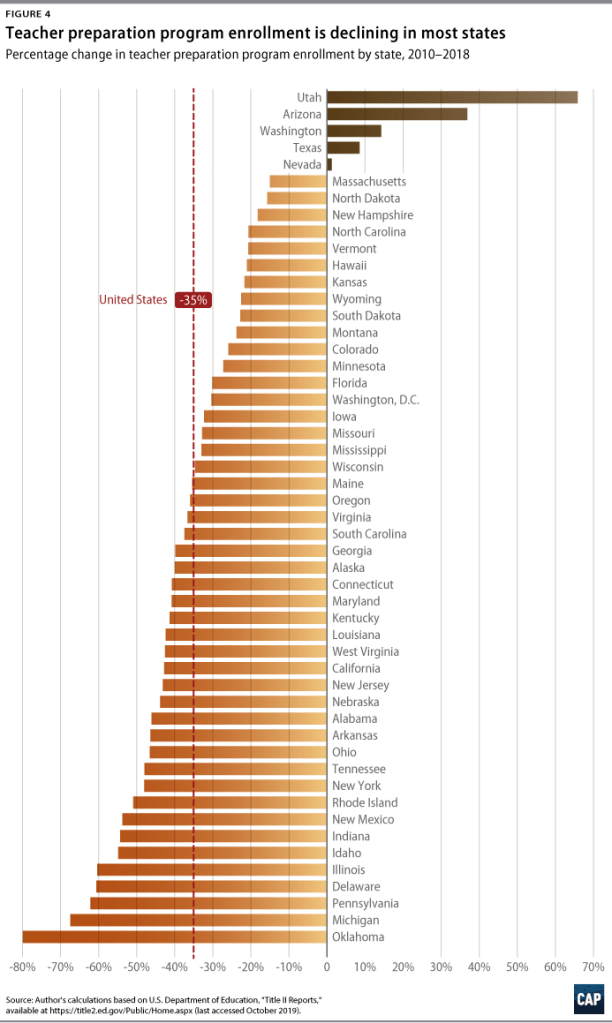

I am proud of those 30 hours in education, because I know what a difference they made in my performance in the classroom. But nationwide participation in traditional teacher training plummeted 35% from 2010 to 2018, and it simply collapsed in Oklahoma, with enrollment down 80%, by far the largest decline in the nation.

Another somber statistic is that in 2009-2010, 1,731 people completed traditional teacher preparation programs in Oklahoma, but a dozen years later that fell to 1,092.

Districts like the one I’ve served for the past 35 years have responded by paying experienced teachers to serve as mentors and having additional training and pull-out days for new teachers to allow them to observe master teachers and seek their advice. But those efforts pale in comparison to the 20 college credits (approximately 60 hours of coursework) I earned in pedagogy plus the additional 18-week internship in my traditional teacher preparation program.

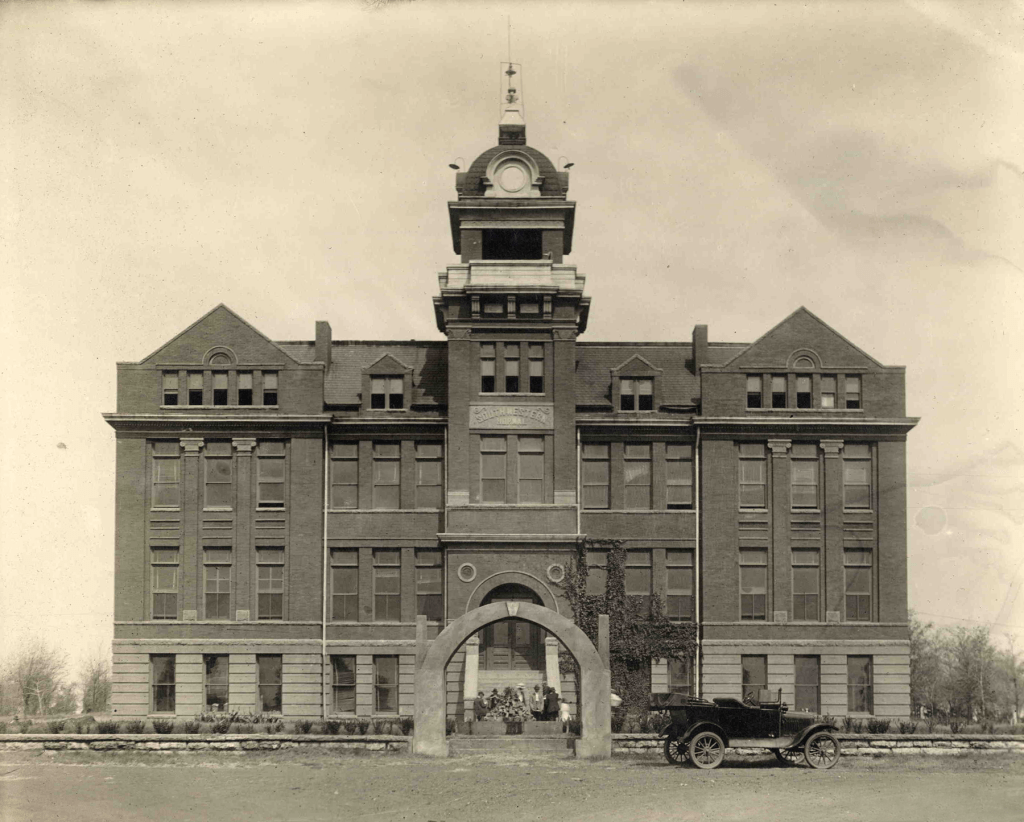

Oklahoma’s Normal Schools

Collegiate teacher preparation in our state was originally done in “Normal” schools. The term arose from the French école normale, a sixteenth-century model school where teacher candidates were taught model teaching practices. The first three higher education facilities established by the Oklahoma territorial legislature in 1890 were OU, OSU, and the Territorial Normal School for teacher training in Edmond. That is now the University of Central Oklahoma, but I knew it in childhood as Central State University, where I competed in an annual piano contest.

Central State Normal was joined by Northwestern Territorial Normal School in Alva in 1897, which became Northwestern Oklahoma State University. That same year, the Colored Agricultural and Normal College was established in Langston for African Americans; it is now Langston University. In 1901, the Southwestern Territorial Normal School was established in Weatherford, which is now Southwestern Oklahoma State University. As a child, I also competed in an annual piano contest there.

After statehood in 1907, three additional normal schools were created in the eastern part of the state: East Central at Ada, which became East Central University; Northeastern State Normal at Tahlequah, which is now Northeastern State University; and Southeastern State Normal at Durant, which is now Southeastern Oklahoma State University.

The normal schools first standardized on six years of instruction: four years of high school courses and two years of college work, with graduates earning a life teaching diploma. They became state teachers’ colleges in 1919, adding two more years of instruction to confer bachelor’s degrees in education. In 1939 they were converted into state colleges to offer additional types of degrees, and by the early 1970s they were comprehensive regional state universities.

OU’s degree-granting College of Education was formed in 1929 by Dr. Ellsworth Collings. Enrollment rose from 100 to over 1,000 by 1946. Think about that: OU wasn’t a former normal school, and it still boasted 1,000 education majors in 1946, when the state population was 2.1 million. By 2022, the state had almost doubled to 4 million, but there were only 1,092 people in the entire state who completed a traditional teacher preparation program.

Collings might be best remembered today for Collings Castle at Turner Falls, the ruins of his vacation home, but I know him for Collings Hall at OU where I took some of my education courses.

Nowadays traditional teacher preparation in Oklahoma is similarly hollowed out. There are still some students who benefit from teachers who had that full-featured preparation, but many who don’t. That isn’t normal, in two different senses of the word.

Thank you for this history. When my mother taught in one-room schools in Missouri back in the ’20s and ’30s, I think she only had to pass a test (and not ride horseback astride–failing to follow that rule cost one of my teacher aunts a potential job). I know she and my dad did go to college, however, one summer at the normal school in Springfield–when I was a baby in 1938.

The first time I was ever in front of any class–as a fulltime new teacher–was here in Bartlesville, back in 1958 (after signing a loyalty oath). I had not had one day of teacher training. Some day I may tell you what I did on my third day of “teaching.”