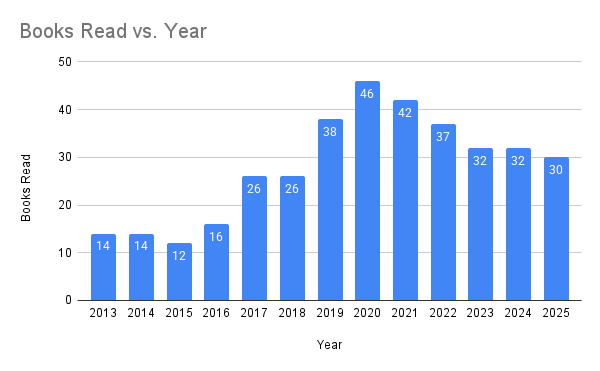

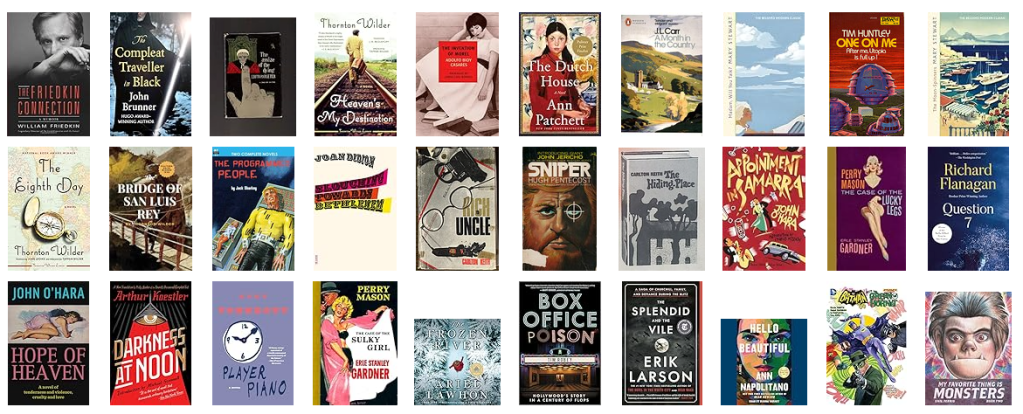

The approaching end of the calendar year led me to compose my fourth annual book report.

I read 30 books this year, the total reduced a bit by my autumn and winter walks having been impeded by lousy weather on several weekends. It took me about 1/3 of the year to finish my latest audiobook.

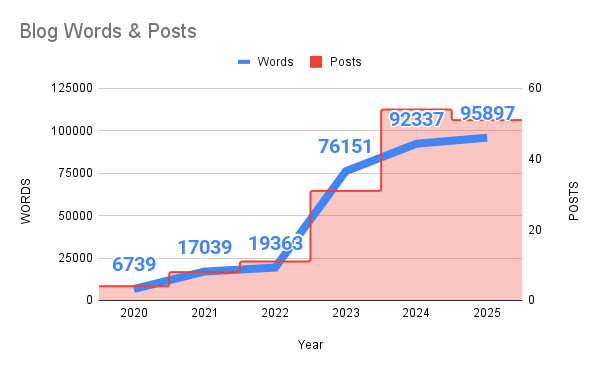

My reading in recent years has also been impacted by my writing, as I have ramped way up from a low of only four blog posts in 2020, thanks to the pandemic, to about one per week, raising my total word count in each of the past three years to novel levels…pun intended.

The two pursuits can complement each other, however. I wrote a dozen book reviews this year. Admittedly, my individual book reviews garner very little engagement, but I enjoy reading others’ old book reviews on the web, and researching and reflecting on a book to write about it enriches the reading experience for me.

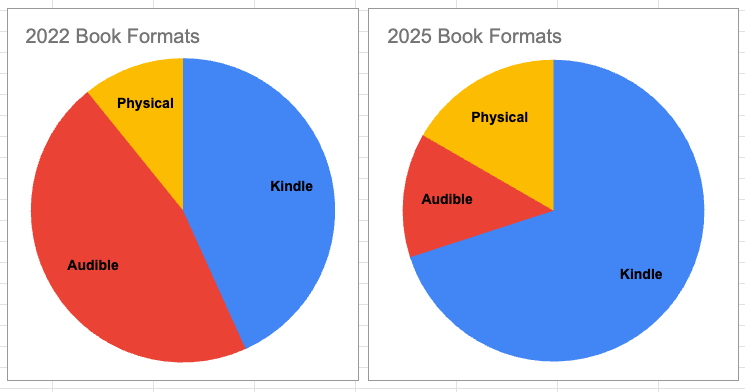

I hadn’t tallied the formats of my reads since 2022, and I discovered that audiobooks were only 13% of the titles in 2025, while back in 2022 Audible and Kindle each accounted for over 40% of the completed titles.

Award-Winning Lit-Rah-Chur

This year I deliberately read more “literature” than in the past, including three novels by Thornton Wilder: The Bridge of San Luis Rey, The Eighth Day, and Heaven’s My Destination. I also read John O’Hara’s Hope of Heaven and his better Appointment in Samarra, along with the disturbing but justifiably lauded Darkness at Noon by Arthur Koestler. More modern award-winning works were Ann Napolitano’s Hello Beautiful, J.L. Carr’s A Month in the Country, Richard Flanagan’s Question 7, and Ann Patchett’s The Dutch House.

Mysteries

I am a bit surprised to find that I read very little of Edith Pargeter this year, having read about three dozen of her mysteries over the years, including 12 of the 13 George Felse and Family novels from 1951-1978 and all 21 of the Cadfael Chronicles published from 1977 to 1994. I have read several of her standalones, and some were quite good, but this year I only read a novella from 1958, The Assize of the Dying, and while its language could be elegant, the plot was beyond belief and the villain had far too little character development. I think I have about a half-dozen of her mysteries still to go, plus a couple dozen other works in other genres I could explore.

Back in 2024 I read the first of the 57 Perry Mason novels, along with a biography of author Erle Stanley Gardner. This year I read the second and third entries in that series. While I was glad to find none of them centered on the courtroom, unlike my recollection of the old television series starring Raymond Burr, the hard-boiled nature of the works and heavy emphasis on plot wore thin for me. I much prefer Christie (whom I’ve exhausted) or Pargeter, so I’ll be giving Gardner a rest.

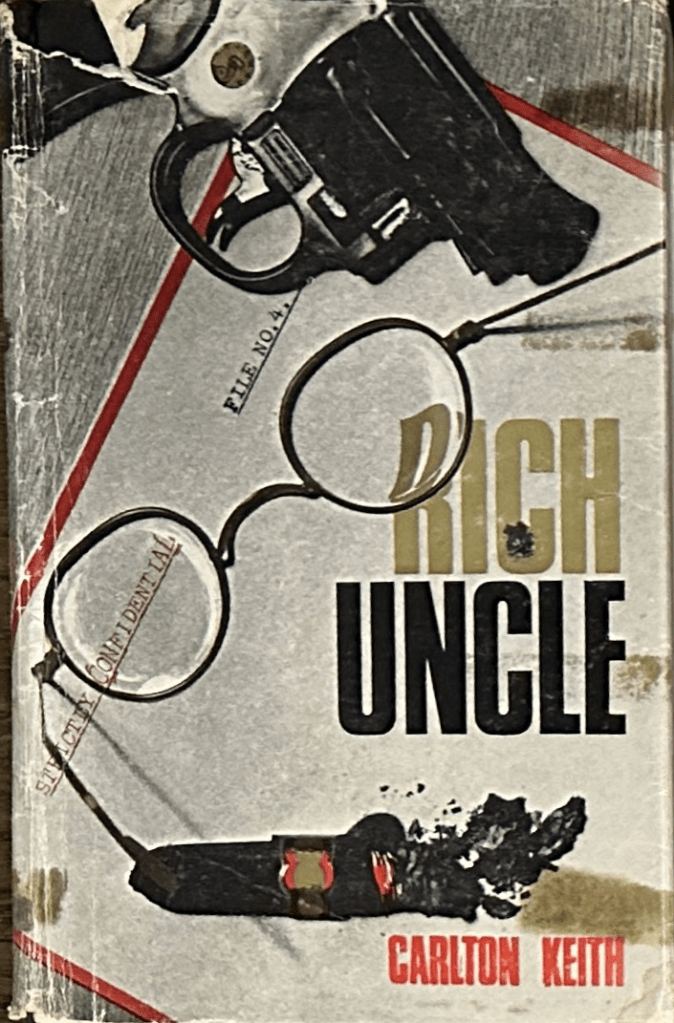

I enjoyed a couple of Carlton Keith mysteries, actually written by Keith Robertson. Rich Uncle was the third of his five Jeff Smith tales, and my favorite thus far. I wouldn’t be surprised if I read another in 2026. They are all long out of print and lack Kindle versions, but I rounded up used copies from across the world back in 2020.

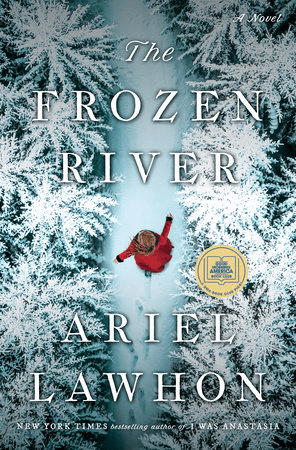

A very different mystery, and the most memorable of the year, was The Frozen River by Ariel Lawhon, a historical fiction novel set in the long winter from November 1789 to April 1790. It was inspired by the true story of Martha Ballard, an 18th-century midwife in Maine, who kept a detailed diary. The various characters and the setting mattered far more than the mechanics of the plot, and the book left me interested in taking up her The Wife, The Maid, and The Mistress and sampling Code Name Hélène. It isn’t easy to get me to read about old New England, having been traumatized in high school by Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter and The House of the Seven Gables, so congratulations to Ms. Lawhon on breaking through the ice.

One mystery for this year is why I never got around to listening to Richard Osman’s fourth installment of the wonderful Thursday Murder Club audiobooks. The solution is that I’ve held onto that treat, waiting for a bad audiobook to put me in need of a sure-fire winner, and I haven’t been out walking as much. It took me months to finish the 19 hours and 20 minutes of film director William Friedkin’s splendid self-narrated memoir The Friedkin Connection, but thank goodness I wasn’t stretching out a mystery for that long.

This year I also read two of Mary Stewart’s romance suspense stories: The Moon-Spinners and Madam, Will You Talk? They were light and fun, with splendid foreign settings, and I look forward to a baker’s dozen of remaining books of that sort which she authored from 1956 to 1997. They strike me as near-perfect escape novels for when I’m out on a patio swing.

Science Fiction & Fantasy

I listened to Kurt Vonnegut’s 1952 debut novel, Player Piano. It was dystopian, odd, but entertaining. He was clearly influenced by Huxley’s Brave New World and Orwell’s 1984, drawing upon his work in General Electric’s public relations department when he interviewed scientists and engineers about their innovations. I need to read more Vonnegut.

The Programmed People by Jack Sharkey was pure pulp, and not in a good way, while Tim Huntley’s obscure One on Me was much better. I also read La invención de Morel, written in 1940 by the Argentine author Adolfo Bioy Casares, and I’ve scheduled a post on that as part of a series of related weekly posts in March 2026.

I read little fantasy, but given my increasing sci-fi skepticism, I decided to try five related fantasy stories by John Brunner, a prolific genre author who had a run of spectacular science fiction novels from 1968 to 1975: Stand on Zanzibar, The Jagged Orbit, The Sheep Look Up, and The Shockwave Rider. Over twenty years, starting in 1960, Brunner wrote five short stories about The Traveller in Black, who periodically journeys across a landscape, countering chaos by answering the spoken wishes of people around him, always with consequences they did not foresee. All five stories were collected in 1986’s The Compleat Traveller in Black.

I enjoyed his skill at creating an unsettling mood and a sense of a distant time through his prose. His use of archaic terms and phrases reminded me of Gene Wolfe’s Book of the New Sun series. An example is when he encouters Lorega, a beautiful woman, beside the river Metamorphia, which changes anything that enters it. She urges the Traveller to join her in swimming in the river, as while she is beautiful, she lacks sense, and hopes a swim might change that.

“I shall not. And it would be well for you to think on this, Lorega of Acromel: that if you are without sense, your intention to bathe in Metamorphia is also without sense.”

“That is too deep for me,” said Lorega unhappily, and a tear stole down her satiny cheek. “I cannot reason as wise persons do. Therefore let my nature be changed!”

“As you wish, so be it,” said the traveller in a heavy tone, and motioned with his staff. A great lump of the bank detached itself and slumped into the water. Its monstrous splashing doused Lorega, head to foot, and she underwent, as did the earth of the bank the moment it broke the surface, changes.

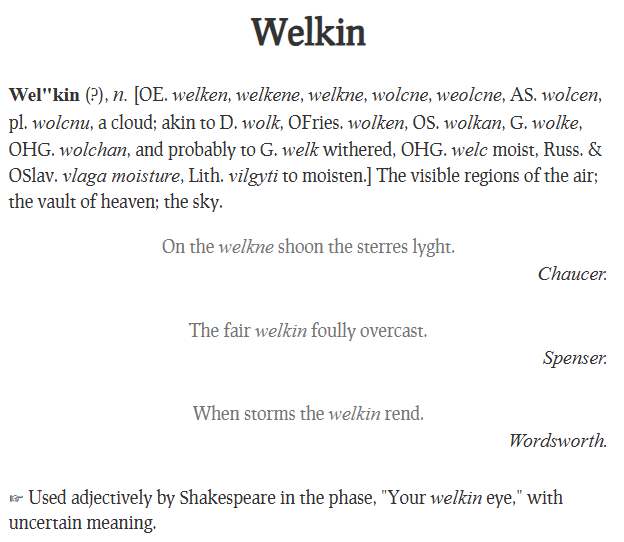

Thoughtfully and a mite sadly, the traveller turned to continue his journey towards Acromel. Behind him the welkin rang with the miserable cries of what had been Lorega. But he was bound by certain laws. He did not look back.

The welkin? Webster’s 1913 explained:

Each story in the collection is a more elaborate variation on the theme. Spread across a couple of decades in various magazines, the tales likely held up, and I am glad that Bruner took the opportunity to make his fifth and final story in the series a finale. However, when collected together they became too formulaic and wore out their welkin.

Nonfiction

Almost 90% of my reading was fiction this year, a marked change given that from 2007 to 2022 over 40% of my reading was nonfiction. This year’s nonfiction consisted of Joan Didion’s essays in Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Tim Robey’s roll call of cinematic disasters in Box Office Poison, the aforementioned Friedkin Connection memoir, and Erik Larson’s fascinating portrait of Winston Churchill during the Blitz in The Splendid and the Vile.

What a contrast that last saga was to our era of politics. Churchill was an egocentric and eccentric mess, but he saved democracy in Europe with his unwavering wartime leadership against fascism.

I did begin another non-fiction book late in 2025, but I don’t expect to be able to tally it as a finished read until after the new year. It is out of print without a Kindle edition, but I bought the 1999 second edition of Good Vibrations by Mark Cunningham five years ago, and I’m finally getting around to it. Thus far it is quite good.